|

|

Lt. Ben Williams, Jr45th Infantry Division |

|

Home |

Who We Are |

Want to volunteer |

Photo Gallery |

Venturing Crew |

Schedule of Events |

Unit History |

Wounded Warrior Project |

Links |

Table of Contents |

45thInfantry Yahoo Group has replaced the message board! |

Looking for Thunderbird gifts? Would you like to help support this website? Please stop by and visit the Gift Shop! |

Benjamin Atticus Williams, Jr

(F Company, K Company )180th Infantry Regiment

11/6/1919 ~ 1/16/2010

Above: Lt. Ben Williams and wife Corinne circa 1944.

The following information was taken from the family biography of Ben A. Williams, Jr and is used with permission of Hunter Williams. huntwilli@gmail.com

When Pearl Harbor was bombed in December of 1941, I was in school at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. While I was home for Christmas I went to Norfolk and volunteered for the Naval Reserve program. The following spring, I was playing a game of baseball and was hit in the eye by the ball. At the time, I didn't realize the impact this would have on my service during the War.

The Navy called for me after I had graduated from Law School in June of 1942 and I went to Indoctrination School at Notre Dame. I completed all the courses required to become a Naval Reserve Officer. Unfortunately though, the injury to my eye prevented me from being able to pass the eye exam and therefore unable to become an officer in the Naval Reserve. I was discharged from this program, and no longer had a choice in my military service. I was now eligible for the draft.

Back in Courtland, I was living with my mother and Corinne and I were dating. Corinne was teaching in Waverly. After about a month of being home, I received an anonymous letter in the mail. It read, "If you're not yellow, it's high time you do something." I suspect the writer was one of two people. Shortly after that incident, I was called up by the Army and went to Fort Lee right outside of Petersburg, VA. This is where I began to learn about life in the Army. The first day they lined us up and said they wanted ten volunteers for table waiter. But to my surprise, those that volunteered were allowed to leave and I was one of the ones that was chosen for that particular duty. About three or four days later, they called again for volunteers for another assignment. Thinking I now knew the ropes, I volunteered. But that time they ended up taking me!

I really missed Corinne and my mother. One morning while headed to the mess hall, I decided I was going to go see them. Somehow I ended up catching a ride to Courtland. Irene Kitchen was teaching in Petersburg at that time and gave me a ride back to Fort Lee. I was able to get back through the gate without trouble, but when I got back to the barracks I discovered someone had packed up all my stuff. Before long I realized someone had done me a favor because we were shipping out that night on a train to Georgia.

We ended up at Fort Gordon where I went through the thirteen week Basic Training program. During Basic we did a lot of drilling and work on the rifle range. We learned map reading and military courtesy. We would go on twenty-five mile marches with a full field pack. I was able to apply for Officer Candidate School. I was selected for OCS and was sent to Fort Benning, Georgia. I graduated from OCS in August 2, 1942. I remember that day in particular because it was the day I got to go home! I was to report to Camp Walters, Texas in two weeks, but while I was home Corinne and I were married. The only thing I remember about Camp Walters was that it was hot. After being there for a period of time I was assigned to the 89th Infantry Division in Colorado Springs. Corinne and I drove out to Colorado Springs in a 1941 red Plymouth Convertible that we had bought.

This division was an experimental light infantry division that was to be trained to fight in the mountains. I was a 2nd Lieutenant and had command of a platoon. We had very little transportation. Each battalion only had a handful of jeeps. The division was sent to California to train in the mountains. We were near King City, which is about halfway between San Francisco and Los Angeles. Corinne drove the car back home to Virginia from Colorado Springs. Then she and her friend, Mildred Whiteside, took the train from Virginia to meet me in California. We trained in the mountains near the Hearst Castle. We would haul equipment in these little carts up and down the mountains. We also used mules to help carry our machine guns and rations up these narrow paths, but every now and then one of them would fall off. We had been there about three months when the Army decided we didn't do too well in the mountains so they sent us to Louisiana to train in the swamps.

After training in the cold and mud in Louisiana, the Army decided to disband the division altogether. From that point I was sent to Durham, North Carolina to Camp Butner. I was going to be sent overseas without being assigned to a division. I had been promoted to a 1st Lieutenant, but would be a replacement officer and would get assigned to a division once I arrived in Europe. I left the United States in a convoy that sailed from New York in the summer of 1944. We left in a large convoy of Liberty ships and destroyer escorts. As an officer, my accommodations were much better than those of the enlisted men who were down in the cargo hold of the ship. I shared a room with about six or seven other officers. During the daytime, we could also go out on the deck of the ship. However at nighttime, everything was blacked-out on the ship so the German submarines couldn't spot us as easily. We had not been out of New York very long before the rumors started spreading around the ship that enemy submarines had been seen and were trailing the convoy. I can't remember how long that trip lasted, but it was long.

We went to Scotland, up the Firth of Clyde to Glascow. There we got on a train and went to Southampton, England which was the staging area for American troops headed to France. After a brief stay in England, I went over to France shortly after D-Day. I first went to Epinal where I was assigned to the 45th Infantry Division who had just taken the city from the Germans. There I was told that I was to go to 2nd Battalion and be platoon leader for the 2nd Platoon in Company F of the 180th Infantry Regiment. The 45th Division had been in action in Italy since the middle of 1943. They were a veteran Division that already seen combat in Sicily, Rome, the amphibious assault landings at Anzio and in Southern France. I received a letter from home that the husband of my first cousin Besse Davis had been killed in action. His name was Doug Rogers and, as it turned out, had been in Company B of the same Regiment I was just assigned to. I joined my unit in the foothills of the Vosges Mountains prior to an upcoming offensive that was to take us to Alsace- Lorraine.

At this time, I was twenty-four years old, had no combat experience, and found myself in command of a platoon of veteran soldiers at the front of the Allied advance in France. I got to know my platoon sergeants and tried to earn the respect of my soldiers. One in particular was Sergeant Larson. He was from the hills of Tennessee. I don't recall him having a great deal of education, but he had a whole lot of common sense and was a real steady fellow. He helped me a great deal. That was the first time I had ever heard of Roy Acuff, who was a country music singer back in those days. Sergeant Larson sure thought Roy Acuff was something. Many of these men were older than me, but they were good guys. I remember another soldier named Wise who was a thirty-eight year old man from Maryland. He shot a rabbit one day, cooked it, and gave me some. It was good!

I remember the first day I experienced combat. It was winter and getting cold and rainy. Two things happened. First, we were moving forward and came to a German machine gun nest. It was firing right across our path. I was designated to take a squad of my men and work around behind the machine gun. We did and lobbed hand grenades. A group of German soldiers came out with their hands up. We took these men prisoner. Later that same day, my platoon was protecting the right flank and I was up there with the lead point. There were four of us. One in lead, one on my left, one on my right, and I was in the middle. As we started up a hill, we got pinned down from rifle fire and grenades. The soldier on my left was killed. I got a piece of shrapnel in my side that went through my field jacket. They had to bring a tank up there and fire over our heads with machine guns so we could crawl out. I received a Purple Heart and a Combat Infantry Badge.

Under the provisions of War Department Circular Number 408, 17 October 1944, the following named Officer, Infantry, of the organization indicated, is hereby awarded the "Combat Infantryman Badge" for exemplary conduct in action against the enemy.

This was the first time while in command of 2nd platoon that we had seen heavy contact with the enemy. I learned quickly that this was not an 8-5 job. Before it got dark, we would set up some sort of defensive position, but when we were on the move we didn't sleep much. My job would be to space the men out to defend against counter-attack and decide if the men should dig in. Most of time we would dig in and sleep in our foxholes. I had a runner, so either he or the platoon medic who would dig my foxhole while I was out checking on things. A lot of times we would send a patrol out to find out what was in front of us. One night I had to go out on patrol with a squad in the snow. We were supposed to meet up with a squad from B Company. We came upon a dead German soldier, but we didn't touch him because the enemy was known to booby-trap dead bodies. B Company didn't show up, so we were wandering around in the dark for hours. My feet were frozen and the next morning I had to thaw my boots before I could get them back on my feet.

One night, we'd relieved another company and were out in a big hole in the ground. We had orders to send a patrol out. One of my sergeants was to be the squad leader. It was his turn but he refused to go. I had to bust him, demote him right there and send him back. Hell, nobody wanted to go. The kid that I promoted right there to be squad leader was a whale of a kid named Ernie Ernot.

Sometimes they'd bring up blankets or bedrolls from the rear because you couldn't carry all that stuff. You'd get one, throw it on the ground and sleep in it. Then you'd wake up usually before first light, warm some water, get some coffee and eat either a C-Ration or a K-ration then start the whole thing over again.

Another time I remember we were moving up what I would call a draw with a path over on the left side. I had a radio operator assigned to me that day because we were out in the front of an attack. He had a big SCR-300 radio on his back so I could stay in contact with the company commander or battalion commander. One of our tanks hit a land mine. I started over to the tank with my radioman right behind me. He stepped on a shoe mine that I must have stepped right over. We were in the middle of a minefield. The medic and I were able to get the wounded man over to the damaged tank without triggering any other mines. That night it was raining and cold and one of those nights we never got a bedroll. It was rocky soil, so we pecked into the ground trying to dig a foxhole to keep warm. That next morning we looked up and about ten feet away there was this big anti-tank mine.

Most of the time, we'd go from one little town to the next little town. We were in some cities, but usually it was a small town or village. Once we'd take the town, we might have a day or two of rest. We'd get into a farmhouse and build a fire, eat some warm food and sleep. When we were in France, in Alsace-Lorraine, we'd sometimes find civilians huddled down in the cellars. In Germany, we'd take over their houses and stay in them. The German civilians did the best they could with what was left. We did not hurt them. They were elderly folks.

Occasionally we'd get mail from home. I'd get letters from Deeda and Corinne. My mother sent me a pair of long underwear one time. About every week or so, you'd get new clean underwear and clean clothes and get to take a hot shower. The showers were great! We had some units that would follow us along. They did a good job, the best they could. Most every night, even if we were out in the field or even if it was raining we'd get a hot meal. A few of us at a time would get off the front line and go back to the rear and eat. Maybe you got mashed potatoes and stewed tomatoes, so you'd put it all in the mess kit together.

On Christmas Eve, we were near the German border in reserve and I received the only whiskey ration that I ever had. I recall my platoon standing in a circle and drinking the gin and chasing it with the scotch. Soon after Christmas, we loaded on trucks and moved north to reinforce the breakthrough near the Bulge. There on the 4th day of January, I earned the Bronze Star. We were moving through the woods when we met heavy enemy resistance and I took the action described in the order of the award:

Under the provisions of Army Regulations 600-45, as amended, a Bronze Star Medal is awarded to the following officer. BENJAMIN A. WILLIAMS 01323268, First Lieutenant, Company F, 180th Infantry Regiment, for heroic achievement in action on 4 January 1945 near Wimmenau, France. While attacking enemy positions on high ground near Wimmenau, Lieutenant Williams' platoon encountered intense enemy mortar and machine gun fire which caused a temporary halt in the advance. Making a quick estimate of the situation, Lieutenant Williams moved through the enemy fire to place his men where they could offer the most protection for the company's flank. Then, guiding a supporting tank to the targets, Lieutenant Williams, although forced to take an exposed position in order to do so, directed such effective tank fire that two enemy machine gun positions were neutralized and the platoon was able to continue its advance to the objective. Entered the military service from Courtland, Virginia.

If the tank had stayed with us we could have captured a number of Germans. The ones that weren't killed or wounded were able to escape. This is where the young soldier Ernie Ernot fell dead at my feet. I'll never forget that - I still wake up at night and recall it.

On January 14th, we were proceeding up a hill in the woods when we took incoming artillery fire. The Germans would set their artillery shells to burst in the treetops so not only would you have metal shrapnel flying around, but splintered wood as well. A piece of shrapnel hit me in the chest. My platoon medic was right next to me. He rolled me over, gave me a shot of morphine, and got me back to the aid station. On the way back to the aid station a call came for me to go to E Company and take over command because their company commander had just been killed. I went back to the regimental aid station and then back to a field hospital where they just patch you up a little bit. My company commander, Jack Treadwell, came to see me. I had been there for seven or eight days and had not received much medical care. The wound had become infected. Jack knew a nurse who was able to clean me up and sew up the wound. Pretty soon after that I was sent on a hospital train to the 46th General Hospital.

This trip took two or three days, the hospital was in France right near the Swiss border. The Red Cross nurse on the train was a movie star named Madeleine Carroll. She passed out cookies. I was laid up in the hospital with all that snow falling. It was a big a relief to be there and not on the front line for a while. Corinne got a telegram that said I'd been wounded. That's all she got. She was teaching school over in Severn, North Carolina.

I was there eight weeks taking physical therapy. The major muscles on that side of my chest had been severed by the shrapnel. I was able to get letters out to Corinne and Deeda to let them know I was okay, but it took several weeks for them to make it back to the States. The first therapy they gave me was to tie my hand on a wheel and make it go around in circles. Then I had to walk my fingers up a wall. I could only walk them up the wall a little bit cause my arm was so badly injured that I could hardly use it.

The roughest thing was to have to go back to the front after I knew what the heck was up there. When I did get back to the front lines, they let me hang around the Battalion Headquarters for a day or two. While I had been in the hospital, the Regiment had crossed the Siegfried Line into Germany. The Siegfried Line was a fortified defensive position the Germans built with tank obstructions and concrete pillboxes. There had been heavy fighting. My company commander from F Company, Jack Treadwell, who had helped me get my chest wound treated, received the Medal of Honor for his action at the Siegfried Line. He single-handedly cleared six pillboxes. These pillboxes had machine guns in them and were connected with trenches running from one to the other. I slept in one of them one night, there was paneling on the inside. It was nice.

I was then assigned to K Company as executive officer. K Company had done a magnificent job crossing the Siegfried Line and received a Presidential Citation for their action there. We got down to the Rhine River and had to cross it in small assault boats. The Germans had this artillery observer airplane that would fly around after dark. We called him 'Bedcheck Charlie.' These planes would be looking for anything they could direct their artillery to shoot at. The plane's engine had a certain whine to it so you always knew when one was around. At night, we went down to the river and the engineers were there with the boats so we climbed in the boats and went across. I went across in the first wave and I'm glad I did. By the time they came back to get the second wave, the Germans were waking up and started shooting at the boats. When we got over on the other side, there was a lot of confusion because it was dark and we didn't know where our troops were.

About three days or four days later I was up towards the front. I don't know whether it was a bullet or mortar shrapnel or what, but something hit my finger. I reckon it was broken, but it also got infected. This time, they put me on a C-47 cargo plane and I flew to a hospital in Paris to get treated. This was an Army cargo plane that had two pilots and just benches you could sit on. I looked up there and the pilots weren't doing a thing. I didn't know they had an automatic pilot. I stayed in the hospital about thirty days, but was able to get out some and see the city. I went to the Follies and to Versailles Hall.

Going back to the front in Germany I went on a train of boxcars. We were taking back people that had been court-martialed. If these soldiers would go back to the front, the Army would do away with their court martial. Every now and then, when the train would slow down, you'd see a barracks bag go off the side and a GI right behind it. After the boxcar ride, I rejoined the Division at Dachau concentration camp. Dachau had been liberated by another regiment in our division. The conditions there were horrible. I saw the bodies in the crematorium and the starving prisoners still there. Years later on a beach in Florida, I was talking to a man in his sixties. He was a German living in Canada. He told me how horrible it was of the Allies to bomb German cities and kill thousands of women and children then proceeded to tell me there was no such thing as the Holocaust. But as described above, I had seen the conditions at Dachau firsthand.

Once we crossed the Rhine, most German units were on the run using delaying actions by the SS troops. They had logistic problems. They didn't have enough gasoline for their planes. We'd see planes backed off of the Autobahn in the woods because they had to use the Autobahn for runways. Things were really coming apart, but there still was some heavy fighting around Nuremberg. There were some SS units still putting up a fight. I will say though, that the American army had more imagination. The Germans had to go right by the book. We were on the offensive and it's a lot more risky being on the attack than defending. So to accomplish objectives we had to take more chances.

We rode on into Munich in the face of a few SS snipers. The Germans surrendered on May 9th, 1945 and we took charge of a large number of prisoners. After a few days there, the chaplain let me use his jeep to find my old F Company. When I found them, there was no one that I knew. Since I had been wounded in January, everyone I knew from the Company had been wounded or killed in action.

While in Munich, I took two nice trips. One trip was with my good friend Hugh Moore, who was a Colonel in the 5th Armored Division. He somehow found me and got permission for me to go with him to Austria to locate a place for his Division to set up a rest camp. We found a lake that had a castle in the center that could only be reached by boat. I can't remember the name of it, but it was built by Ludwig II, the "Mad King of Bavaria." It was something to see. There were rooms in it which had fixtures made of gold, silver, and porcelain. The second trip was with Lt. Bushyhead, an Indian from Oklahoma. The 45th Division was originally a National Guard unit from Oklahoma and there were many Native Americans in the ranks. We established a friendship and he got a jeep and driver and asked me to go with him. We went through the Swiss Alps down to Brenner Pass in Italy. It was beautiful! Why I never contacted him later after the war, I will never know.

The Regimental Personnel Officer, Capt. Wells went to Division and somebody looked into my records and discovered that I had a law degree. I was made Assistant Personnel Officer and eventually became Regimental Personnel Officer. As a result of that, it was my duty to make the preparations for the transfer of the Regiment back to the States. We eventually arrived back in the States, sailing into New York harbor on the English luxury ship Aquitania which was a sister ship of the Lusitania. I was home in Courtland for forty-five days and then went to Brownsville, Texas where the paperwork for the deactivation of the Division was completed. I received recognition in the Division history book for my work in completing this projects as follows:

First Lieutenants Ben Williams, Courtland, Va., James E. Stodgel, Dayton, Ohio, and Second Lieutenant Russel L. Fenn, East Paterson, N.J., of our Personnel Section and their enlisted assistants did a fine job in preparing our Regiment administratively for the prospective moves.

I don't want anyone to think I'm some sort of hero. I was scared the whole time I was there. The Germans had these 88's, which were high velocity artillery guns that were originally designed to be anti-aircraft guns. They discovered they could also use them to great effect as anti-tank weapons and against infantry. They made a distinctive noise when fired. They also put them in their heavy Tiger tanks. I remember crawling around in a vineyard on a hill overlooking a small German town. One of these Tiger tanks was down there shooting up into the hill. We could hear the shells as they went over our heads and saw the tank as it was firing. The tanks, the mortars, the machine guns, they were all scary. It's just one of those things I had to do. You don't have any choice and you wouldn't want to desert. You wanted to do your part, but I would not have minded if someone could have discovered that I had a law degree before I was sent to a Rifle Company.

Occasionally though we found ways to escape the traumatic events that we experienced on a daily basis. I remember being in a small town on one side of a river and the Germans were on the other. My forward observer and I were in a house overlooking the river. We decided to try and get a mortar round to land in the chimney of a house across the river. We called in adjustments to our mortar position over the radio. We never did get one to go down the chimney, but the house was destroyed. We also wasted several mortar rounds, which was not a good idea, but for those handful of minutes we were just having fun.

I was discharged as a Captain. Upon being examined for discharge, I was asked if I wanted to put in for disability for the wound to my chest. When I was advised it would take several days for the physical and paperwork, I said "No, I guess I will just go on home." However, I do now receive a sum each month from the Veterans Administration. When I got back from the war I just wanted to forget about the whole thing and get on with my life. Forget it happened. As bad as it was though, if I had to...I'd do it again. It gives me a real sense of accomplishment being part of something that had such an impact on world history. I thank God for seeing me through it.

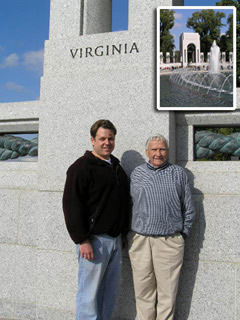

Above: Ben Williams and grandson at the World War II Memorial, Washington DC, November 2004

Page originally prepared by Hunter Williams. Last revision