A

Different 9.11 | |

| In September 1940, the 45th National Guard was mobilized and sent to Fort Sill for training. Driftwood native Lynn E. "Jerry" Gerber knew a number of the men who were mobilized with the 45th. "They begged me to go with them," said Gerber. "I said, "I'm not going to do it, I don't want to go."" Just a few months later, however, Gerber was among the first young men drafted from Alfalfa County and was immediately shipped to Fort Sill., became a prisoner of war for 20 months after being captured in Salerno, Italy. Gerber, was a member of C Company, 179th Infantry Regiment, 45th Division. His first taste of Army life, he says, was not the best. "I'm to find out in the next two years that the infantry only does two things," Gerber wrote, "they dig foxholes and they walk. Then they walk to one more location and they dig another hole." Gerber was drafted in peace time, with an eye on possible war. That possibility became reality Dec. 7, 1941, with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. His one-year draft hitch was three weeks short of ending, but the resulting declaration of war changed that. In 1943, Gerber was shipped to North Africa. He took part in the invasion of Sicily, going ashore just before daylight July 10, 1943. Sept. 11 and Dec. 7 have historical identities all their own. They are instantly recognizable for what they represent. But

say Sept. 11 to Lynn E. Gerber, and the story is very different. The "9-11"

that played such a huge role in Gerber's life was during World War II - Sept.

11, 1943. | |

|

Gerber

was a foot soldier born in Driftwood in northwest Oklahoma. He was a member of

the 179th Infantry, 45th Division. He had been drafted in January 1941 - 11 months

before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the U.S. into World War II

officially. |

|

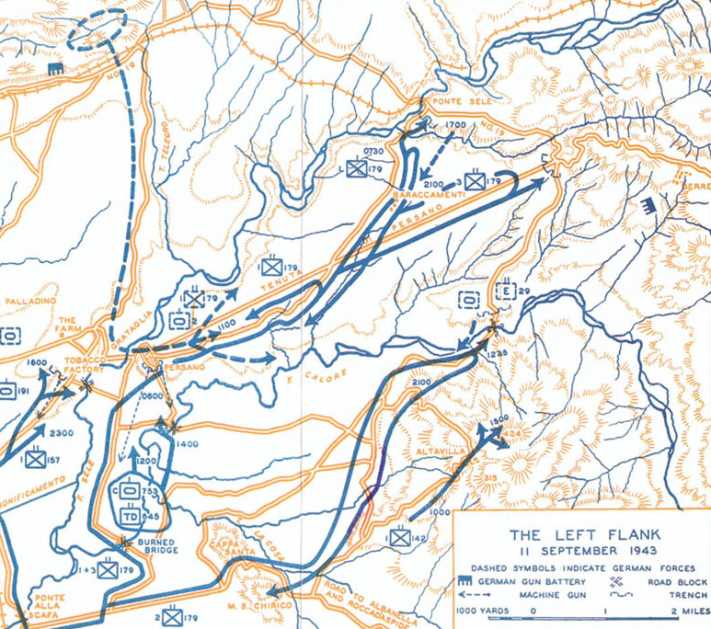

| About 3 in the

afternoon, the 179th was ordered ashore to fill in a gap widening between the

36th Division and the British on their left. On the way to Salerno a torpedo passed beneath the flat-bottom landing craft in which Gerber was riding, scraping the hull of the craft on its way to exploding harmlessly on the beach.

They began moving inland in the darkness - walking. They were encountering no opposition. Where were the Germans? They wondered if they were walking into something, and, yes, they were. The German forces just stepped aside and trapped the entire regiment - front, sides and rear. Gerber's platoon was pinned down in a ditch alongside a fence row and gravel road, when four German 88-millimeter shells hit the fence about 8 to 10 feet from Gerber. "All of the shrapnel sailed over our heads," Gerber said, "but I was totally deaf for a couple of hours, with a bloody nose. "As the afternoon moved on, we had nearly made it to a riverbank when I spotted a German tank firing with five Germans moving along behind it," Gerber said. "They were moving across my front from behind a big elm tree, about 500 yards away. "I was on my belly, just drawing down on them, when a machine gun blasted me from the right side. The whole burst was ricochets. I was hit in the right leg, left leg and side. "Right then, three Germans came out of the trees on the right. I didn't see them coming at first, and they were on me before I could move," Gerber said. "I remember screaming and hollering and rolling over, and the Germans sticking bayonets in my belly and throat. One grabbed my rifle by the barrel and broke it against a tree, and said in broken English, 'Vor you ze var ist offer.'" "I tried to get up," Gerber said, "but I couldn't. So they were correct - as of that moment the war was over for me." The Germans helped him bandage up the bullet holes the best they could, gave him a cigarette and then went on with their part of the war. One German stayed behind to guard Gerber and some other wounded. "I dug the bullet out of my right leg with my pocketknife," Gerber said. "I guess that was kind of dumb because of infection, although I did have sulfa powder to sprinkle on it. "I never found the other rounds that hit me, although I found the holes they made in my clothes. I suspect they were spent, being ricochets. At nightfall, we were taken to a front-line hospital." Gerber's 20 months as a prisoner of war had begun. Back home, his parents began making funeral arrangements, believing their son had been killed in the fighting in Italy. But his young bride was sure he was alive and wouldn't allow it.His young wife, Ila, whom he married not long before being sent overseas, and his parents were notified Gerber was missing in action. His parents made arrangements for a funeral, but Ila clung to the belief he was still alive, a fact confirmed just before Christmas that year when a message came from the International Red Cross Gerber was being held prisoner. It was just before Christmas - three months later - when his family was notified Gerber was a prisoner of war. Gerber said he was moved a lot during those three months, from one Italian village to another. He said he got the same care as German wounded. He almost lost his right leg three weeks into captivity. Gerber said it was black and swollen, and a German doctor told an orderly if it did not look better the next day they would have to amputate it. About an hour later, according to Gerber, the orderly returned with a large roll of paper bandages and a large bottle of brown-colored liquid. "All day and all night the orderly kept the bandages soaked and warm," Gerber said. "The next morning, the doctor took a look at my leg and said I could keep it."The Germans treated his wounds in a series of hospitals, one housed in an old monastery. The old building had a long, narrow hall to the inside latrines, a hall in which bodies were piled each morning in preparation for burial. One morning when Gerber was on his way to the latrine, he saw one "corpse," bandaged head to foot, that had rolled off the pile and was on his hands and knees trying to find the latrine. Gerber said the Germans kept moving them north ahead of the advancing Allied armies. He was held in Rome for awhile in a building in sight of the Vatican. He also stayed in four POW camps inside Germany - Lamsdorf, Hammerstein, a location near Berlin and finally to Luckenwalde, near Potsdam. To get to the last camp at Luckenwalde, the POWs, escorted by German officers on horseback, were forced to walk 125 miles through 6 inches of snow, carrying their belongings. It took them six days to make the trip. GIs who were unable to make it, and who dropped out, were shot by the Germans, according to Gerber. A Good Samaritan German guard and a German farm family might have saved Gerber and 29 others from falling out and being shot during the grueling march. It was on their third night out on the long march, when 30 of the men were billeted in the hayloft of a barn on a German farm. It was about 9 p.m. when the German guard informed the men the housewife was cooking dinner for them. They were escorted five at a time to the house to eat. "I was in the third group of five that got to go," Gerber said. "All five of us were seated around a big kitchen table. There was black bread and real butter, two boiled eggs, cooked chicken, fresh milk and boiled potatoes. "The lady had a wash boiler full of potatoes, all cooked. They fed all 30 of us that night," Gerber said, "and took the risk of being put before a firing squad. "Somewhere today in central Germany, there is a family with a halo above their heads, and this ex-GI remembers and is still giving thanks in their memory," Gerber said. Gerber was liberated when a Russian tank, commanded by a large Russian woman, crashed through the front gates of the camp. Jerry had received a few heavily censored letters from Ila during his captivity, but none contained any news of what was going on back home. After being liberated, Gerber was sent to Le Harve, France, to await transport home. One day he was sitting in a tent when he heard someone calling, "Anybody by the name of Gerber live around here?" He looked out of the tent and saw his brother, Earl, a sailor off a Navy destroyer tied up at the Le Harve docks, walking past. It was then he learned that, after he was captured, Ila had joined the Navy and was stationed in Jacksonville, Fla. After a five-day trip across the Atlantic on a Liberty ship, the returning prisoners entered New York harbor. "I saw the lady with the torch in the harbor at New York City," said Gerber, "boy that was beautiful." Armed with the phone number of the Jacksonville Naval Air Station, where Ila was stationed, Gerber found a pay phone and made a long distance call. "I asked if I could speak to Seaman First Class Ila Gerber," said Gerber. "It wasn't 10 minutes and I heard her say hello. I'll tell you, that was the prettiest hello I ever heard in my life." While waiting for Ila to be discharged from the Navy, Gerber took a temporary civil service job. His assignment? Working at the German POW camp in Alva. When the German prisoners found out Gerber had been a prisoner himself, they "gave me a wide berth." But Gerber bore the Germans no ill will, and they eventually grew comfortable around him. Despite enduring lice, dysentery and an occasional beating, he is not bitter about his POW experience. "I wasn't mistreated," he said. "Anything that came under the Geneva Convention, we had it." He is philosophical about his experience. "I never in my life saw anything honorable about being a prisoner of war," he said. "But being an ex-prisoner of war has got its good points, because the Lord led me into it, and out of it, and he's still leading me. So why couldn't I be proud to be an ex-POW, because I sure wasn't proud of it when I was there." He came home to a hero's welcome. He said it looked as if the entire area around Burlington and Driftwood turned out to greet him. He also learned his young bride, Ila, whom he had married just before going overseas, had not been sitting at home. She had joined the Navy and was stationed in Florida. Gerber is certain his life was pre-destined. "I look back," he said, "and see the Lord has been in complete charge since the first day. And he still is." Lynn and Ila Gerber have been residents of Enid's Golden Oaks Retirement Village for 10 years. ©Enid News

& Eagle 2003 " | |

last revision