REPLY BY ENDORSEMENT - JANUARY 1942

Recently

a patient presented me with a copy of her husband's orders. It was to confirm

his transfer of assignment from Ft. Benning and establish her eligibility for

CHAMPUS (Civilian Health Medical Program Uniformed Services). Listed at the bottom

left under the heading, "Distribution:" were 17 different departments,

headquarters and individuals for which copies (totaling 138 in number) were to

be supplied.

Government bureaucracy, and especially armed service bureaucracy,

has long had a love affair with paperwork in order to cover every possible contingency,

plug every loophole and diffuse responsibility. Contemplating the inordinate amount

of secretarial work, time and paper consumed in providing just this one individual

transfer order recalled an initial shattering experience with the paperwork of

a Line of Duty board in the Army thirty years ago.

In January 1942, after

four months in the Army assigned to the old Station Hospital at Benning, I was

just becoming adjusted to the duties of a 1st Lt. In the Medical Corps. Out of

the blue one day came notification (in triplicate) of my assignment as medical

officer on a three-man Line of Duty board. By mistake, since my date of rank was

the most recent of the three, I was listed as the Presiding Officer. The other

two members, 1st Lt. Evans (Infantry) and 2nd Lt. Hellman (Signal Corps), turned

out to be novices also.

In panic, I sought out a knowledgeable army surgeon,

Capt. Max Rulney (3 years of doctoring in the C.C.C. and 3 years in the army),

whose expertise in paperwork far exceeded that in medicine. The obvious irregularity

in assigning me as presiding officer upset Max greatly, but, as a practical man

well versed in the devious ways of the military, he recommended not attempting

to straighten out the mistake about date of rank. The paperwork, he said, might

become so involved that it would be easier for the board to meet as constituted,

turn in its report, and have done with it. Besides, as the senior presiding officer,

I would be merely a figurehead, and the actual work would fall to the lowly 2nd

Lt. Hellman, who, automatically, was the recording secretary.

The large

scale Louisiana maneuvers had ended in the fall, and, as part of the exercise,

the evacuation channels for casualties were being tested. The Station Hospital

at Benning had been designated as a base hospital outside of the combat zone to

which wounded were shipped for definitive treatment and rehabilitation. When recovered,

the evacuee would either be returned to his original unit, reassigned elsewhere,

reclassified or retired, as the case demanded. The particular job of our Line

of Duty board was to investigate the broken leg injury of a maneuver casualty

and establish a Yes or No answer to the simple question of whether the injury

had occurred "in line of duty."

Before convening the board

for its first meeting, I thought it wise to visit the Orthopedic wards across

the road in the cantonement area to find and interview our casualty. Landry, Jules

A. Pfc. was a pleasant, non-complaining draftee with his left leg encased in a

walking cast. His name and unmistakable Cajun accent indicated he was Louisiana

lowland native. He was cooperative and happy to talk with a fellow Louisianan,

and gave a detailed, straightforward account of his earlier accident.

Landry had moved with his infantry unit from Camp Blanding in Florida to Louisiana

for the maneuvers. Early one Sunday morning, after a strenuous week of simulated

combat, his company was out of action and in reserve, bivouacked in a spot less

than a mile from his home. The thought of Sunday dinner and some of Mama Landry's

crawfish bisque was too much for Jules. So, with nothing to do, and being afraid

to awaken his sleeping platoon sergeant to ask for permission, he took off down

the familiar road and spent the day with his admiring family. After lunch, he

took Alcide, a 4-year-old younger brother, for a ride on the family mule. Returning

home, the mule balked, Jules was thrown and snapped both bones in his lower leg.

The family took him to old Dr. St. Amant in the nearby town, who splinted the

leg, loaded Jules in a car and delivered him back to his company area. Unfortunately,

by this time, Landry had been listed as AWOL on the daybook, and the report had

gone too far through channels to be retrieved.

This, essentially, was

the bare story of Landry, Jules A., Pfc. and his broken leg. Our board held a

meeting and decided, in view of the locale of the accident and Landry's being

officially AWOL, that the injury obviously had not occurred "in line of duty."

Lt. Hellman prepared the report consisting of our decision along with 20 pages

of statements, X-ray findings and true copies of medical and other reports (all

in quintuplicate). With much relief we all signed and sent it off through channels.

Two weeks later the report was back on my desk with an added front sheet

marked "Urgent" and something called a "1st Wrapper Endorsement."

It had apparently gotten no farther than the Station Hospital's own administration

office and had been returned for "revision and correction."

Again seeking help, I approached the redoubtable Capt. Rulney who was sympathetic

but not at all surprised. Max pointed out some glaring errors in phraseology,

the absence of certification on a number of true copies, and, worst of all, that

the inexperienced Hellman had typed using half-inch margins instead of the required

one and a half. From his files, he supplied a standardized Line of Duty proceedings

report to be used as an example, and, certainly, by comparison, ours was definitely

the work of amateurs.

Armed with the original report and the example,

I went across post to the Signal Corps area, only to find that 2nd Lt. Hellman

had been transferred to Alaska two days before. Lt. Evans was easier to find,

but, unfortunately, he was leaving immediately on a ten-day field exercise. He

did promise to take over as recording secretary as soon as he got back.

Discouraged (and worried about that "Urgent", 1st Wrapper Endorsement)

I prepared the second report myself, paying careful attention to word sequence,

terminology and margins. Evans signed when he got back, and the new, revised report

(in quintuplicate) along with the original report and its Wrapper Endorsement

was sent on its way again.

This time it got as far as the Main Post Headquarters.

When it reappeared on my desk 3 weeks later there was another "Urgent"

and a 3rd Wrapper Endorsement (what had happened to the 2nd Wrapper was never

explained). It was sent back for "completion" this time, and apparently

needed a statement (and 5 true copies) from the civilian physician who had originally

treated Pfc. Landry. This required some doing since old Dr. St. Amant was not

a letter writer by nature, nor had he yet been paid for his efforts. When finally

his grudging reply did come, copies were made and certified, and a complete new

third version of the board proceedings was retyped. In the interval, however,

Lt. Evans had been transferred to a port of embarkation and was not available

for signing. So true copies of his orders had to be obtained, along with a certified

statement from his former commanding officer, and sent along with the report.

While Evans' departure simplified matters in regard to calling board meetings,

it left me wary, and, as the new report along with the previous two went off,

I had no doubt that I would be seeing them all again before long.

They

got to Corps Headquarters this time and it was 5 weeks before they reappeared.

Marked "Urgent" again and sporting innumerable new Wrapper Endorsements,

another signed statement from Pfc. Landry was needed now. A quick trip to the

Orthopedic wards confirmed the certainty that Landry, Jules A., Pfc. had long

since departed and been returned to his unit in Florida. From other sources, it

was learned that Landry's Division was already in transport overseas. Nothing

was left at Ft. Benning but a harried Presiding Officer and the growing stacks

of papers and Wrapper Endorsements. There was nothing to do except to add a statement

from the Orthopedic ward officer and a summarizing acid appraisal of my own and,

all in quintuplicate, the new report and the three old ones were packaged up and

sent off again.

Before the calculated time for its next reappearance - it

must have reached Washington on this trip, since it was gone more than 5 weeks

- orders came through transferring me to the 45th Division at Ft. Devens, Mass.

The final outcome of Pfc. Landry's Line of Duty board remains in limbo.

I was haunted during the entire time of combat in Italy by a fear that the next

runner coming up the rocky path to the Aid Station in the mountains above Cassino

would be carrying a manila-wrapped package bulging with those familiar papers,

requesting that I reply by endorsement. And even now, thirty years later, there

is a feeling of unease on seeing any suitably sized, official looking package

that measures more than two feet in depth.

(c) The Bulletin of the

Muscogee County (Georgia) Medical Society, "The Doctor's Lounge", Jan

1972, Vol. XIX No.1, p.8

Col.

William H. Schaefer, U. S. Army, Ret.

Last month we attended a pleasant gathering at White's Bookstore where retired

Colonel William H. Schaefer was autographing his newly published book on economics,

Shares. It is a small and interesting volume written in parable form. It explains

in painstakingly simple and logical fashion the monetary system and its fallacies,

and at the end offers some of Colonel Schaefer's uncluttered thinking on what

should be done about this mess.

We have been an admirer of the Colonel

for many years. His unfortunate capture early in the Mediterranean campaign of

World War II, and his subsequent long incarceration as a German prisoner of war,

interrupted an outstanding military career and deprived the Army and the country

of a personality that would have been one of its top General Officers. Colonel

Schaefer might best be described in the words of Dr. William Bean, who spoke of

an eighteenth century English physician as a man who ". . . has lived a life

of quiet rebellion against some of the organized assininities of contemporary

existence." From our own past experience, we can vouch for Colonel Willie's

rebelliousness, his integrity and intellect, and his direct, forceful approach

to problems.

|

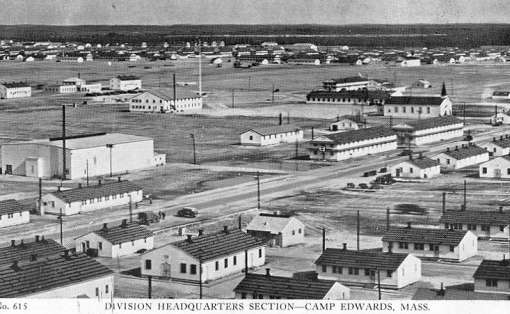

The

45th Infantry Division was the first Unit to train at Camp Edwards. |

In

the summer of 1942, as a Battalion Surgeon with Colonel Schaefer's 500 man special

force, we accompanied this first unit to undergo training at the newly established

Army Commando Training Center on the south shore of Cape Cod. The installation

was so new that we spent the first week clearing brush, digging latrines, building

facilities and making the area habitable. Along with a rigorous training program

we were supposed to be learning the amphibious techniques of shore to shore landings.

As so often happens in military planning, the initial confusion was great.

Landing craft were scarce in those days - and the one or two dozen needed to float

our embryonic commandos had to be obtained from four different commands - the

Coast Guard, the Navy, the Marines and the Army Engineers. There was inter-service

rivalry, and each command seemed reluctant to part with any of its hoarded craft.

Coordination of the boat activities was a continuous nightmare. Then

an unexpected medical catastrophe occurred when three hundred of our men turned

up one day at sick call with the typical rash of a contact dermatitis. Emergency

gallons of calamine lotion were rushed to us from the hospital at nearby Camp

Edwards, but for three days all training was disrupted. We soon discovered that

the hand to hand combat course had been laid out in a pure stand of poison ivy.

Adding to the confusion, and to the frustration of Colonel Schaefer and his itchy,

pink-colored commandos, was the fact that the permanent training command staff

in charge of the center were not only inexperienced in basic knowledge of infantry

tactics, but also unbelievably bumbling and incompetent.

At the halfway

mark Colonel Schaefer could stand it no longer. He called a special meeting of

all officers, his own and all of the training command group. In his deliberate

fashion he enumerated each day by day mistake, each inefficiency, each foul-up,

and each indignity that he and his men had had to put up with. At the conclusion

of his controlled tirade, he announced with unmistakable authority (he was West

Point, and outranked the commander of the school) that henceforth, he was taking

over, and would be in charge of all activities.

The last half of our

training went off like clockwork. On completing our course we had become adequately

amphibious, and, as a final exercise, had subdued the island of Martha's Vineyard

in a joint assault with the paratroopers. On graduation we were reviewed by Secretary

of War Stimson and a cadre of Pentagon high brass, who were on hand to observe

and officially dedicate the new school. They were most impressed.

Many

years later Colonel Schaefer told us that the Secretary of War had indeed been

so impressed, that, on his return to Washington, he ordered an immediate blanket

promotion of one grade for every man of the permanent training school command.

Even now, twenty-one years later, Colonel Schaefer still gets mad when he

thinks about it.

(c) Bulletin of the Muscogee County (Georgia) Medical Society, "The Doctor's

Lounge", Dec 1963, Vol. X No.12, p.9

June

1943

|

| | Brigadier

General John R. Kilpatrick, Port Commander, H.R.P.E., 0-167001, on Pier X, with

outgoing troops of the 45th Division, and representatives of local Red Cross serving

refreshments to the soldiers. Newport News, Va. : U.S. Army Signal Corps, Hampton

Roads Port of Embarkation, June 3, 1943. |

Twenty-five

years ago, standing there on the open dockside under a noonday, coastal Virginia

sun that steamed the humid 96-degree atmosphere, our thoughts about War, Army

medicine, and life in the Infantry were all unprintable. There was no shelter

from the brightness, and the sweat soaked through clothing under the full combat

pack and dripped from our wrists. A scattering of wilted Red Cross ladies offering

paper cups of lemonade and melting ice did their best to spread cheer against

insurmountable odds. We had been up before dawn and, staggering under the load

of full equipment, a Valpak and two barracks bags, we had hurried and waited over

and over again on the move that took us from the swampy staging area of Camp Patrick

Henry to the embarkation docks at Hampton Roads. The large gray Navy transport

that loomed above us at the dock was the familiar U.S.S. Thomas Jefferson on which

we had trained in ship-to-shore amphibious techniques just two months before on

a then icy Chesapeake Bay.

The 45th Division, after almost three years

of training, was about to set sail finally for an overseas destination and long

awaited combat. (The 45th along with its sister unit from the Southwest, the 36th

Division, were the first two National Guard Divisions activated by President Roosevelt

on August 1, 1940 " . . . to serve in the military service of the United

States for a period of twelve consecutive months, unless sooner relieved.")

We had joined the Division over one year before at Ft. Devens, Massachusetts

on the same set of orders that included George Schuessler of Columbus, Lee Powers

of Savannah, and Bon Durham of Americus. The 45th, with two regiments from Oklahoma

and one from Colorado, was already a veteran and seasoned outfit when it was sent

from Texas to New England, and was preparing for an immediate overseas move when

we were assigned to it in May 1942. But those plans fell through, as did the next

ones in September 1942 (when General Patton arrived on the scene to deliver an

impassioned pep-talk that included us in the task force to invade North Africa),

and instead the Division had continued to train, - unendingly, it seemed to most

of the men. In the summer there had been two prolonged amphibious training exercises

in shore-to-shore work on Cape Cod and Martha's Vineyard: from November to March

the Division had endured winter maneuvers in the bitter cold and snows of upper

New York State close by the Thousand Islands: and during spring, more amphibious

training with the Navy on Chesapeake Bay, and then a month of mountain training

in the wilderness of Virginia's Blue Ridge chain.

It had been a strenuous

but healthy, pleasant and unpleasant year. Our assignment as a Battalion Surgeon

with the pith (Colorado) Regiment had been quite a change from the dull routine

of hospital duty during the previous year at Ft. Benning. In medical circles,

such an assignment to field duty with an infantry battalion was generally considered

on a par with banishment to Outer Siberia. Field units had difficulty keeping

such jobs filled since immediately on assignment there was a panicky scramble

on the part of any rational medical officer to get the hell out by any means available.

- whether it be by writing a congressman, aggravating a silent ulcer; feigning

insanity, or admitting to homosexuality. Consequently, it was only when an outfit

was on the verge of overseas shipment that these positions could be filled with

unfortunates who, lifted from this post or that on sudden order were given no

time to escape. Of the six of us who were sent to the 157th as new medical officers

in May 1942. only two still remained a year later. But again the positions had

been filled in the staging area, and this time, for the four new doctors. there

was no way out.

It had been a year of medical stagnation. screening healthy

young men, giving shots. holding the endless successions of sick calls: a year

of headaches; sore feet, aching backs, coughs, colds, sore throats and loose bowels.

"Riding the sick book" was an easy war to avoid strenuous duty or an

unpleasant garbage detail, and we could always count on a full house in the Aid

Station on days when a twenty mile training march was scheduled. We learned to

deal with the psychosomatic ailments of the chronic complainers and goof-offs.

(The sick call technique of "Iodine lake" Holnitsky, the nutty medical

officer from the 3rd Battalion who sported a Groucho Marx moustache and read Plato

from a paperback, was to paint everything from a sore throat to a sore rectum

liberally with gentian violet.) The only elective surgery consisted of wart and

mole removals: an ingrown toenail was a major case. The infrequent circumcision

took on the aspect of a stomach resection, and we would draw straws for the privilege

of being an "operating surgeon" again. We inspected barracks, latrines,

shower room duckboards, mess halls, and pots, pans and garbage cans. A Boy Scout

with a merit badge in first aid could have performed most of our medical duties.

But there had been compensations. There was pleasure in discovering the

real function of the Army and participating in the activities of infantry training

and tactics. Life was seldom dull. The new world of the foot soldier, with its

incessant rousing, elemental English, and Rabelaisian humor was always interesting.

We were fortunate in having "Uncle Charlie" Anckorn as our Regimental

Commander, a stern father figure whose erect and dignified military bearing combined

firm discipline with great ability, calm wisdom, understanding, and a quiet sense

of humor. The 157th. under his guidance as National Guard Advisor to the State

of Colorado in the prewar years and under his command since its activation as

a unit, had matured into a capable regiment that functioned smoothly with a minimum

of confusion and flap. Colonel Anckorn was never flustered by the inconsistencies

of conflicting regulations or directives that emanated from Division or higher

headquarters; he merely sidestepped or ignored them. He had the respect of everyone

and the men were devoted to him and the Regiment. In that year we had discovered

the meaning of esprit de corps.

The year had passed quickly. There were

memories of long training marches and overnight field problems along the picturesque

back roads and byways through the woodlands and orchards of the beautiful, summer

and fall New England countryside. On the longer marches, after the first hours

when the joking and chatter would subside there was little joy in marching for

marching's sake alone, and the steady clomp of heavy GI shoes in monotonous cadence

had a sedative, hypnotic effect on all the senses. There were pleasant recollections

of weekend leaves spent in Boston, New York, Baltimore. Vermont and New Hampshire.

Of long walks along the isolated beaches of Cape Cod during the weeks of Commando

and amphibious training; of the coordinated, dawn landing at Oak Bluffs on Martha's

Vineyard, wading through the heavy surf and watching the hazy, pink sky fill with

the multicolored chutes of paratroopers and their equipment arriving to join us.

There was pleasure in recalling the vast expanses of clean, white snow and

drifts that blanketed Pine Camp and upper New York State through the winter months:

the crystalloid trees and the two-story long icicles that hung from the eaves

of the barracks; the poker games in the quarters that lasted for days on end during

the blizzard times when the temperature hung at a steady 30 below and training

had to be suspended. There were memories of a wintry Chesapeake Bay and scrambling

down the ice-coated, chain link nets over the sides of the transport ships into

the bobbing landing craft below, drenched by freezing spray. Of the wild, night

rides by jeep, with Father Barry, the Regimental Chaplain, dodging trees up the

rocky streambeds of the Pope and other, unnamed, peaks in the Blue Ridge. And

the vivid picture, as the mountain maneuvers ended, of a group of us squatting

around a borrowed, field kitchen burner unit on a sloping, desolate clearing at

three in the morning, - drenched by a steady drizzle, brewing K-ration coffee

in our canteen cups; too miserable to move, to wet to care, too tired to complain.

We could only stare, as if in a trance, at the flickering blue flames and wonder

if the night would ever end, or if we should ever be warm and dry again.

But all that was behind us and the last two weeks of confinement in the mosquito-infested

area at Patrick Henry, cut off from family and the outside world, and aggravated

by the endless examinations and equipment checks of the staging process, had played

havoc with morale. The men were irritable, exhausted and over trained; they were

anxious to get moving, anywhere. The long waits were frustrating, and the unbearable,

smothering heat on the embarkation dock was the final indignity.

|

| USS

Thomas Jefferson APA30 |

Moving at a snail's pace. we filed up the gangway and were checked aboard. It

was better there, but not much. The officers, on the upper decks, were crowded

eight to a small stateroom the men were crammed like sardines below decks and

into the holds that were already filled with supplies, weapons, vehicles and equipment.

When the ship pulled away from the dock, it was only to move a short way out into

the harbor where it dropped anchor. We remained there for four more days. Each

morning and each night we practiced the familiar boat drills; over the sides and

down the cargo nets with full equipment, into the waiting landing craft, around

to the other side of the ship where we scrambled up other nets back on board again.

We felt like caged monkeys. Then on the morning of June 6, 1943 we awakened to

the throb of engines and blasts of whistles. We moved slowly out of the harbor,

and the giant armada of more than 100 ships that carried the 45th Division and

all of its attached supporting units, headed out into the Atlantic.

(c) The Doctor's Lounge, Muscogee County (Georgia) Medical Bulletin, Vol XX, No.

1, 1963, p20

July 1943

On the

afternoon of June 21, 1943, the convoy that carried the 45th Division overseas

passed quietly through the Strait of Gibraltar. We lined the rails of our transport,

the U.S.S. Thomas Jefferson, to view the big rock, and wondered jokingly what

had happened to the Prudential Insurance sign. It was our first sight of land

since leaving the Virginia coast thirteen days before. The trip across had been

a smooth and uneventful one. On only two occasions had there been submarine alerts,

and the destroyer escorts had sped by dutifully to drop their depth charges; if

any actual danger existed it had never materialized. Although the amateur astronomers

and navigators aboard had predicted a course toward North Africa, it was not until

we saw Gibraltar that we knew for certain our destination laid in the Mediterranean.

Our 2nd Battalion of the 157th Infantry along with its attached supporting

units constituted a complete combat team that occupied the entire transport. We

were tightly packed aboard, literally in layers, with all of our ammunition, supplies,

weapons and vehicles, ready to be unloaded over the sides into the landing craft

that would assault an enemy beach. The repetitious training had continued throughout

the voyage over. By day there were lectures, training films and calisthenics;

at night, under blackout, we practiced the boat team assembly drills. Medical

duties on board were minimal, and most of the time apart from the scheduled training

was spent in our bunks or in the wardrooms playing gin rummy. The ordered, clean

Navy life in "officer country" was an unfamiliar experience to us of

the earthy infantry, and the Navy mess with its white tablecloths, gleaming silver,

and colored mess-boys, was a world that recalled a pleasant life of pre-Army days.

Morale, which had reached its lowest point prior to sailing, had returned

with the anticipation of imminent combat. But it slumped anew when, after being

confined to the transports for four days in the harbor at Oran, we moved eastward

only a few miles along the coast to Mostagenem to make still another practice

landing. Once more it was down the landing nets into the landing craft and onto

the benches. The "enemy" opposing us was our old buddies from Cape Cod,

troops of the 36th Division. On hand also to greet us as we stumbled dispiritedly

across the sand was the flamboyant General Patton. Resplendent in polished helmet,

gleaming cavalry boots, and ivory handled pistols, he strode up and down the water's

edge, urging us to "Charge!" with flicks of his riding crop. We were

hardly inspired.

The morale was even lower by the end of eleven days

on land and more training. The dry, alkaline barrenness of French North Africa

was unpleasantly hot, water was at a premium, flies, mosquitoes and fleas surrounded

us, and small, grisly scorpions invaded our clothes, shoes and bedding. At higher

headquarters final plans and preparations were being made for "Operation

Husky", but it was not until we had loaded back on the transports, and the

convoy was under way again, that we learned we were to invade that ancient island

battleground, Sicily.

The three-cornered island located strategically

in the Mediterranean off the toe of Italy, had endured invasions and occupations

with monotonous regularity for more than three thousand years. The Sicels and

Sicilians, original inhabitants (and probably foreigners themselves) from the

Stone and Bronze Ages, were first invaded in recorded history by the Phoenicians

prior to 1500 B.C. Then, in succession, came the Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans,

Vandals, Ostrogoths and the Byzantine Turks. In the eighth century A.D. the Arabs

took over for 300 years until displaced by the Normans, who, in turn, lost out

to Spain and the House of Aragon in 1300. The Bourbon Dynasty and the Kingdom

of Naples displaced the Spaniards in the early 1700s, and for the next hundred

and fifty years the island was handed back and forth among the royal houses of

Austria, France and Italy. The British came as allies to the Bourbons in the fight

against Napoleon in the 1800s; and after Garibaldi, the unifier of Italy, invaded

in 1854 to end the Bourbon rule, Sicily became part of the Italian kingdom in

1861. Now the Germans in their role of Axis partner had occupied the island since

1941, and the Sicilians were looking forward once again to liberation, this time

by the Americans and British.

Shortly after midnight, on July 10th, the

USS Thomas Jefferson lay a few miles off the southern coast of Sicily wallowing

drunkenly in the heavy seas. The invasion fleet by now numbered over 2000 vessels.

Invasion hour had been put off until 2:45 AM because of an unexpected Mediterranean

storm which whipped wind and waves in uncooperative fury. We had been assembled

and waiting in the night blackness at our boat team stations along the rails of

the upper decks since midnight. Ordinarily most of us would have been seasick,

but the excitement of the moment had our stomachs knotted in controlled spasm,

and the anticipation and uncertainty of what lay ahead gripped us all.

The landing hour was again delayed, and then just before four o'clock the PA system

droned out its call to the boat teams. We had been due to disembark and go in

with the 5th wave, to land one hour after the initial assault, but the storm had

thrown all into confusion. Climbing down the wet chain-link nets we were slapped

unmercifully against the side of the transport as it rolled with the heavy swells,

but all fifteen of us who made up the boat team managed the final hazardous drop

into the tossing LCVP safely.

Getting the medical jeep and trailer into

the landing craft with us was almost disastrous. The booms would lower the vehicle

to a point above us in the boat, where it swung like a demolition ball gone crazy.

We would pull and strain at the hanging guide line that dangled from the jeep,

and then with the jeep just over our heads and almost in the boat, the sea would

fall away and the line be ripped from our grasp amid curses and shouts of "Turn

it loose!" while the transport rolled one way, the jeep swung up in another,

and our little boat plunged in still another. The next roll of the transport would

carry us up and send the jeep crashing down against our sides or bow as we scrambled

to avoid being crushed. After six or seven attempts, the impossible was finally

accomplished, and with a sputtering roar of the Diesel motor, we cast loose and

headed in the direction of shore.

In all of our practice landings on

Cape Cod, Martha's Vineyard, Chesapeake Bay, and North Africa we had hit the right

beach only once in eight attempts. We didn't improve our average this time when

it was for real. Fortunately, however, as we approached shore the darkness began

to lighten enough that we could see surf pounding against a rocky coast and offshore

rocks. It was not at all like the sloping sand beach of the scale-relief model

we had studied so carefully on board the transport. The fearful bombardment put

on by the naval artillery and air support that had raked the beaches an hour before

had subsided into an occasional salvo that whistled high above us on its way inland.

Since there seemed to be not much activity or small arms fire on the beach itself,

we were eventually able to persuade our frightened and obstinate Navy coxswain

to swing the boat to port and run parallel to land about a half-mile off shore

until we spotted a sandy coastline that seemed more recognizable. Some of the

boats in the waves ahead of us had not been so lucky, and in the darkness had

piled head on into the offshore rocks. The Battalion lost forty-five men by drowning.

In his haste to get us ashore and get back to the safety of the transport

area, our uncooperative Navy coxswain rolled down the landing ramp at the first

grate of keel on sand. We piled over the sides as the jeep and trailer shot down

the ramp into more than three feet of water. We waded along beside the jeep, and

all went well until the waterproofing gave up in the heavy surf. Our initial surge

had covered about 30 yards only; there was still more than 100 yards ahead to

the water's edge. Hip deep in water and with the surf breaking on our backs, we

held a brief strategy meeting and decided in view of the enemy artillery bursts

sporadically peppering the shore and shallows, the jeep and trailer would have

to make it on their own.

Once on the beach we left Corporal Morrow and Red

Meier, the jeep driver, to dig in and keep an eye on the vehicles, while the rest

of us sought out the access road inland that would lead us to the Battalion assembly

point. Actually, by our maneuvering off shore, we were within a couple hundred

yards of where we should have been. Kenny Prather, the Staff Sergeant in charge

of our medical section, scouting on ahead, returned in a few minutes with six

happy Sicilian prisoners. They had been manning machine guns in a pillbox nearby,

and were overjoyed that they had a choice of surrendering to a first-aid kit and

a Red Cross armband, rather than to a trigger-happy Gl. They had been afraid that

they might have had to shoot at someone in self-defense. We turned them over to

Morrow and Meier and hiked off to find the Battalion.

By noon the Battalion

had secured its first objectives. Apart from the men lost on landing there had

been few casualties, and we treated these in our first aid station set up under

an olive tree near the battalion headquarters. With Sgt. Prather, we walked back

to the beach and found that Morrow and Meier, with the aid of the prisoners, had

manhandled the jeep and trailer onto the sandy shore. The motor had dried out

and was running again, but when they tried to reach the access road, both jeep

and trailer had bogged down hopelessly up to the tire tops in the soft sand. We

all pitched in to dig it out, cleared a path in front of it, and sought out the

engineer boys, who had landed by this time. We borrowed two long rolls of chicken

wire, jammed some under the dugout front and back wheels, and laid out the rest

in a path in front of the jeep. When all was set, we lined up on each side of

the jeep and trailer. Meier gunned the engine, and with a mighty heave and spinning

of wheels we launched the jeep onto the wire netting, It advanced three yards,

but used up all thirty feet of chicken wire, which ended up tightly wound around

both front and rear axles.

For the next two hours, while the war swirled

around us and the boats kept landing and the shells kept dropping. We took turns

under the jeep with wire clippers, snipping each strand of chicken wire individually,

and cursing the engineer geniuses. Some time later when the half-tracks rolled

ashore we were pulled out onto firmer ground. Motorized again, we roared off to

catch up with the rest of the Battalion.

Although we were ignorant of

it at the time we were landing on, fighting on and marching over a site of great

antiquity that had seen destruction and sea borne invasion many times before.

On the rocky promontory to our right, and on the fertile dunes in front of us,

the town of Camerina, founded 600 years before the birth of Christ, had been destroyed

and rebuilt five times before it was eventually abandoned. In 405 BC, at the time

when Syracuse, some eighty miles away on Sicily's eastern coast was the center

of Greek civilization and the most powerful city in all Europe, Camerina had been

wiped out by an expeditionary landing force of Carthaginians led by the first

Hannibal, grandson of Hamilcar. It was rebuilt by Timoleon, destroyed and rebuilt

twice in the interval, and finally destroyed again by the Romans in 258 BC. It

lingered on as a shell until, during 1st century BC, it gradually disappeared

forever.

The rocks that form the promontories and line the shores today are

not really rocks but fragments of composition building stone, remains of the shattered

walls and temples of five Camerinas. Our own modern bombs and explosives had done

little damage; the rubble, merely disturbed and rearranged by our shelling, returned

again to the centuries of nature once we had passed. Today all that remains of

a great Greek civilization is a small patch of archeological excavation recently

uncovered. All that remain from the brief German occupation are the empty concrete

pillboxes overlooking the vulnerable beaches. With the Russian Navy now well established

in the Mediterranean, these will probably be put to use again before the century

is out.

(c) The Bulletin of the Muscogee County (Georgia) Medical

Society, "The Doctor's Lounge", Jul 1968, Vol. XV No.7, p.9

Combat

Medicine: Summer, 1943

In mid-August, the midnight mist rolling in from the sea across one of the

few straight stretches of road on the north coast of Sicily was chilling. There

were five of us in the jeep; Meier drove and I sat in the front seat beside him;

Watkins, Caronte and Prather were crowded into the back and complaining of the

cold. Meier, peering intently ahead into the fog and blackness over the lowered,

canvas covered windshield, was doing his best to make time while dodging potholes

and shell craters along the war-torn road. The trailer behind us bounced crazily,

loudly rattling its half-load of water cans, litters, splints and plasma boxes.

"I hope the god dam Krauts are busy up ahead," grunted Watkins

between bounces. "Turn on the lights and blow the horn, Meier, maybe they

ain't heard us yet."

Beyond the battered two-story shell of rail

station on the left, we dodged a burned-out half-track partially blocking the

road. The smell of combat and death still lingered along the debris-strewn highway,

where, only two days before, the tanks and tank destroyers had fought a running

battle with the retreating Germans. Now, defending a ridge that dropped abruptly

to the sea about three miles ahead, the outnumbered Germans had stopped the advance

of Patton's entire Seventh Army as it pushed eastward toward Messina.

A half-mile farther on, a guide waving a white handkerchief mounted the road shoulder

and flagged us down. He turned us onto a dirt track leading inland toward the

dark hills and mountains.

"You guys are late. The rest of the battalion

came by over an hour ago."

"It ain't our fault, buddy," said

Caronte. "Where the hell is the assembly area?"

"About a mile

or two up this road," said the guide, pointing.

"Thanks,"

grumbled Caronte. "Cap'n, I can smell it already. Another chicken shit mission."

The broad band of rugged mountains along the entire north coast of Sicily

extends inland for more than 30 miles, rising rapidly in places to heights of

6000 to 7000 feet. There is a narrow coastal plain in spots, but, for the most

part, the main highway and the railroad beside it are chiseled into mountain rock

just above the water's edge. The infrequent roads leading southward from the coast

hairpin up the mountainsides usually to dead-end in some remotely perched town

or village high above the sea. In the mountain fastness, only narrow goat and

donkey trails, winding in and out along ravines and ridges, connect the isolated

villages.

The 157th Infantry's 1st Battalion had been engaging the Germans

for two days in a bloody and unsuccessful attempt to push them off the strategic

ridge, which met the sea below the mountain towns of Motta and Pettineo. East

of the ridge was the wide, dry bed of the Mistretta River and, beyond that, lay

the town of San Stefano di Camastra on the coast. In order to outflank the Germans

on the ridge, our 2nd Battalion had been called upon to make a forced march over

the inland mountains to the south. To aid in hauling weapons, ammunition and supplies,

the Division's company of mules and muleskinners had been brought up. About one-quarter

of the battalion, and all of its vehicles, had to remain in the rear. Initially,

only company medics and litter-bearers were to accompany the flanking foot-troops,

but, at the last minute, someone decided that a group from the aid station should

trail the battalion in with extra medical supplies and equipment. As usual (it

was early in the European campaign and combat medics had yet to be discovered

and glamorized) the orders had reached us belatedly.

By the time we reached

the blacked-out assembly area, a barren hilltop of scrub brush, gorse and cactus,

it was evident that Caronte's estimate of the situation was correct. The assembly

point was deserted except for a couple of supply men.

"We saved

you a mule," said one of the supply sergeants.

"That don't look

like no god dam mule to me," said Watkins, eyeing a tiny, long eared, moth-eaten

Sicilian donkey, which, materialized out of the night mist.

"Where the

hell is the pack saddle?" asked Prather.

"The heavy weapons boys

took the last one."

"How do they expect us to load all this crap?"

"That's your problem."

"Typical! Typical!" said

Watkins. "Screw the medics! Always on the short end."

Watkins,

a red-faced, balding cynic and semi-reformed alcoholic, had once been chief morgue

attendant at Denver General Hospital. Caronte was a short pudgy, comical Brooklyn

native who left a job in the Shirley Temple Doll Factory to join the Army. Only

Ken Prather, Staff Sergeant in charge of our medical section, was truly at home

in the outdoors. In civilian life, Ken had lived on a ranch and herded sheep in

the Colorado mountains near the Great Divide. Three years in the infantry had

reinforced his natural silence and preserved a lean hardness.

We unloaded

less than half the supplies we'd brought and sent Meier with the jeep and trailer

back to the rear. Using a folded GI blanket as a saddle pad, Prather fashioned

some rope slings to drape across the donkey's back. (Caronte had already christened

her Angelina; in honor, he said, of his stubborn grandmother.)

[Editor's

note: The author fails to mention here that his own grandmother, born not more

than 50 from miles from this very location, was Angelina Tusa, and that it was

she who loaded her own small children into a donkey cart for Palermo, and from

there by steamer to the port of New Orleans in 1892. But that's another story

- see "My Father the Doctor".]

Through the sling loops

on each side, we suspended folding litters and a couple of metal-frame leg splints.

Several rolls of broad, muslin splint-bandage fashioned into a wrap-around girth

secured this basic load. The rest of the equipment blankets, plasma boxes, miscellaneous

cartons of medical supplies and food rations was piled on top and tied to the

splints and litters with more rope, adhesive tape, muslin and gauze bandage. We

roped two 5-gallon water cans together and hung these, one on each side for balance,

across Angelina's withers. She seemed to tolerate the unholy load, but it took

strong urging to set her into motion. With Prather leading and scouting ahead,

Caronte on the halter rope, Watkins and I trailing, we set off into the darkness.

Fourteen hours later, at four in the afternoon, we were still moving,

but slowly. Through the night and through the day we had pushed on; up and down

hillsides, following ravines, gullies and dried out streambeds whenever we could;

only occasionally had we found a track or path we could use. We proceeded by guess,

by map, and Prather's compass reading. Three times, on upgrades or downgrades,

the load had slipped and we were forced to stop, unpack and reload. It was a lonely,

frustrating journey. The war, it seemed, had disappeared. Once or twice during

the day, in the distance beyond the mountain ranges between the sea and us, muffled

sounds of shooting and artillery fire reached us. Otherwise we were alone in the

dusty, deserted, sun-baked countryside, and only the sounds of Angelina's reluctant

hooves, the constant creaking of her makeshift load, and the clank of water cans

broke the silence. It became evident that we were lagging more and more behind

the battalion. We had seen none of our own men, and even the few peasant huts

we'd passed were empty. The hot Sicilian sun was merciless. By afternoon our sweat

soaked woolen uniforms were stiffly caked with fine, white dust. We had finally

reached a terrace of stunted olive and almond trees amid clumps of broadleaved,

prickly-pear cactus at the base of the Motta ridge.

"I think Angelina's

had it," said Watkins.

"That makes two of us," said Caronte.

"My feet are killing me."

"Okay, get her unloaded," said

Prather. "We'll give her a rest and cool her off with some water. And we

might as well take a chow break ourselves. Maybe in a couple of hours we can get

her moving again."

We emptied one of the water cans into our helmets

and canteen cups and doused Angelina and ourselves. She refused to eat K-ration

dog biscuits but bit off half of a hard chocolate D-bar Caronte held in his hand.

He was disgusted. "She's got a sweet tooth just like old grandma. Jeez! I

never thought I'd be playing nursemaid to a butt-headed Sicilian jackass."

"She loves you, Louie," said Watkins. He was sitting, propped against

a rock wall, spooning out a can of cold pork and beans and guzzling red wine from

one of his two canteens.

Prather and I puzzled over our one field map. "We

ought to be about here," said Prather, "and by now the battalion should

be over here almost to the coast, behind where the Germans are supposed to be

on this ridge."

"At the rate we've been going, it may take

us another 7 or 8 hours to reach them."

"Maybe more," said

Prather, watching Watkins who had been hitting the wine all day.

"It

still looks like we've got a long climb ahead of us. If we can ever make it to

the top of this ridge we should cross a road that leads inland to Motta."

"Yep. But it runs in the wrong direction. Look," said Prather.

"There's a dotted line here which must be one of these cart paths leading

off it that loops around to the north again and passes close to the coast about

where the battalion should be."

At dusk, for the first time in several

hours, the sound of artillery fire started again. It was closer now, but still

muffled and far away near the coast. It kept on.

"Somebody's catching

it," said Caronte. He waddled over and kicked at Watkins who had snoozed

peacefully through it all. "On your feet, Wat. The Krauts are coming."

"Blow it"

"Let's pack up and get moving," said Prather.

We reached the top just past midnight, after a tortured nightmare of

scrambling. We had zigged and zagged upward, one rock terrace after another in

unending succession, some of them barely wide enough to support one row of olive

trees or a couple of rows of staked grape vines; Caronte and Prather pulling on

Angelina's halter, Watkins and I boosting from the hind end. Twice more on the

climb we'd had to stop and repack the load. The road was there on the crest, and

it was deserted. We were all exhausted.

"Somebody's gotta be nuts,"

groaned Caronte. "No god dam battalion in its right mind ever came this god

dam way."

Prather had walked ahead along the road and returned within

a few minutes. He seemed relieved. "I found the cart path. Right where the

map said it was. It'll be easy going from now on."

The path took off

from the road and headed east about a quarter mile from where we were. It led

along the north slope of a ridge just below the ridge line. Once, in a spot where

the mist was thin, a sliver of moon broke through the cloud cover high above and

we caught a glimpse of the sea, far below and miles to our left. For the first

half-mile the path was smoothly graveled, but it soon changed into a cobblestone

surface just wide enough for a narrow animal cart. In places it was bordered by

a regular, raised, stone edge; in places, too, wheel ruts, worn deeply into the

stone, testified to its antiquity and once heavy use. Watkins, even though he

still nursed a wine hangover, seemed jovial. "If I had more wine, I'd drink

a toast to them god dam old Roman road-builders."

(On

a visit to Sicily many years later, I found the road again. Actually, it predated

the Romans and once led from the large Sickle-Greek city of Halaesa, which had

flourished nearby in 500 B.C. The Romans may have improved the road during their

occupation, but Halaesa itself disappeared around 100 A.D.)

We

were moving comfortably now on a gentle downhill grade. The night had darkened

and the mist was heavy again. If all went well, we should be reaching the coast

in five or six hours.

We came to a stop as Caronte halted Angelina suddenly.

"What the hell is that?"

"Sounds like music," said Prather.

We listened intently. Faintly at first, then disappearing completely,

then again, waxing and waning, we could hear a thin sound of music. The eerie

melody, somewhere in the mist ahead, obviously was on the path and coming toward

us as it got progressively louder. Then, only a few yards away, emerging out of

the fog, came a peasant leading a small replica of Angelina loaded with straw

and a couple of wooden wine casks. He was playing a concertina. When he stopped,

he was almost on us; it was hard to tell who was more surprised. He was a small,

weathered man, dressed in typical peasant fashion, wearing dusty, frayed trousers,

a shapeless cap on his head, and a nondescript, dark woolen coat draped over the

shoulders of a dirty, open-necked shirt of coarse cloth.

Watkins was

first to react. "Speak to him in Wop, Caronte. Ask 'him what in the hell

he's doing out here on this Godforsaken mountain at two A.M. Don't he know there's

a war going on?"

After the initial surprise, our peasant friend seemed

entirely at ease. Caronte tried out his best pidgin Brooklynese Italian: the peasant

answered in an almost unrecognizable Sicilian dialect. There was a lot of hand

waving and good fellowship. I could pick up only a word or two.

"You

don't have to kiss him, Louie", said Watkins, "What's he telling you?"

"He says his name is Giuseppe, Joe Mazzara, and he's on his way home.

He's got a cousin in Yonkers."

"Jesus," said Watkins. "They

all got cousins somewhere."

"He says the Germans pulled out yesterday."

The peasant nodded vigorously. He brushed one open palm quickly and dramatically

against the other in the direction of east: "Tedeschi, tutti scappati!"

"That's what they always say," said Prather.

"Caronte,"

said Watkins, eyeing the two wine casks, "you're a lousy intelligence corporal.

Find out if he's interested in trading us some wine for cigarettes."

The peasant grinned: "Americana? Buono."

Watkins tapped on one

of the casks, held a couple of empty canteens upside down and conveyed the message

adequately in sign language and two words: "Vino? Cigarette?"

After filling Watkins's canteens, Mazzara insisted that the rest of us take some

too. The wine was harsh and sour, but warming. After a round of drinking, the

peasant struck a small wax match and lit one of his bartered cigarettes. A few

minutes later we broke up the party. He waved goodbye and continued up the trail

with his donkey; we moved on in the opposite direction. The concertina music began

again, and, just before it faded away in the distance behind us, he must have

stopped to light another cigarette. The mist had cleared somewhat, and the reflection

of the match flare, even from a great distance, shone like a beacon.

"That's one bastard who never heard of a blackout," grumbled Watkins.

A minute later the first shell exploded near the trail about a hundred yards

to our rear. Six or seven more, all hitting on the ridge or near the cart path,

followed it. The brief warning whistles were unmistakable. "Mortars,"

yelled Prather. "Let's get off this road."

We scrambled down about

three levels onto a terraced grape vineyard and sought protection along a low

rock wall. Another barrage of mortar bursts came whistling in, exploding along

the trail we'd left. A third barrage followed, and then all was quiet.

"I knew there was something phony about that character," said Watkins.

"I bet he was a god dam German agent infiltrating the lines. He must have

had a walkie-talkie with him and spotted us for the Krauts."

"You're

so smart," said Caronte. "Why the hell didn't you challenge him?"

"With what? A 5cc syringe?"

"You could have poked around

in that straw while he was dealing out the wine."

"Yeah. And supposin'

he had a burp gun slung under that baggy coat. Where would we be?"

"Nuts,"

said Prather. "Knock it off. The shooting's over."

We decided

to abandon the path and stay put where we were for the rest of the night. Angelina

was unloaded again and we tied her halter rope to a vine stake nearby. We stretched

out on the rocky ground along the wall and went to sleep under some dusty grape

vines.

Suddenly, it was morning and broad daylight. Caronte was shaking

my arm. "Cap'n. Wake up. The donkey's gone and so is Prather."

"Where's Wat?"

"Still passed out under the grape vines. He

finished off the wine and a pint of grain alcohol last night before he went to

sleep."

"Well, see if you can revive him. I'll heat up some water

for coffee. We'll eat breakfast and wait here for Kenny. He'll be back."

It was an hour later when we spotted Prather heading our way on the trail

above. He was leading Angelina. She had pulled loose during the night and wandered

off, dragging stake and grape vine at the end of her halter rope. Prather found

her about a half-mile away nibbling on cactus leaves. After tying her up temporarily,

he had gone ahead on the trail for a couple of miles and run into a squad from

H Company.

"They were pulling out and heading toward the coast to

rejoin the battalion," said Prather.

"Did they have any casualties?"

asked Caronte, still thinking about the shelling a few hours before.

"Nope.

One guy had a headache and wanted some APC's."

And what the hell were

they doing last night while the Krauts were shelling the bejeesus out of us?"

asked Watkins.

Prather grimaced. "According to the way they told it,

they spotted some lights and activity on this ridge last night and blasted the

hell out of a whole company of Germans."

"Holy tomato! And I could've

stayed in Brooklyn making dolls," said Caronte. "Well, anyway, I'm glad

them heroes are a bunch of lousy mortar men."

We reloaded Angelina

and started on our way again. Within three hours we had reached the coast, still

looking for the battalion. There was traffic now on the coast road. A jeep and

trailer approaching us from the direction of the front looked familiar. Prather

was up on the road flagging it. It was Meier.

"Where have you guys been?"

he asked. "I've been up and down this road for the past two hours looking

for you."

"What's going on?" asked Prather.

"Nothing,

now. The Germans pulled out yesterday afternoon, and they moved the rest of us

up the coast road last night," said Meier. "A couple of platoons from

G Company are already across the river and into San Stefano."

"Did

the battalion trap any Germans?"

"Naw. They were long gone before

our guys even reached the coast."

"Where's the battalion now?"

"Up ahead," said Meier, "sitting on their duffs. We been ordered

to hold. There's a big rumor that the whole division is gonna be relieved. We're

waiting for the 3rd Division to move through us this afternoon."

"My

achin' back," said Watkins, aiming a kick at Angelina's scrawny rump.

Caronte climbed into the jeep, pulled off his shoes, and began massaging his feet:

"What a chickenshit war."

(c)The Bulletin of the Muscogee County (Georgia) Medical Society, "The Doctor's

Lounge", Sep 1973, Vol. XX No.9, p.11

|