The Journal of

James R Safrit

Introduction and

postscript by his son Mike Safrit

edited by Eric Rieth

Introduction

|

|

James

Safrit 1945

|

James R. Safrit, Jr. was born

on September 5, 1920 in

Rowan County. His parents were James R. Safrit, Sr. and Sally Grace Foster

Safrit. He was the great-grandson of Confederate Veteran Peter A. Safrit,who

had served with the 4th N. C Infantry Regiment, a part of Robert E. Lee's

famous Army of Northern Virginia during the Civil War. Peter Safrit had

been twice wounded and twice captured. He spent the last year of the conflict

in a US hospital and prisoner of war camp and was finally paroled when

the war ended. Peter A. Safrit was 5'8" tall and had blue eyes and

weighed about 160 pounds. Ironically, James R. Safrit was also 5'8"

tall and weighed about 160 pounds.

James Safrit was a resident of

China Grove and attended China Grove Schools through 7th grade, but had

to drop out and go to work for the Cannon Mills textile company to support

his family during the Depression. Fortunately, Cannon Mills continued

to run throughout the Depression and he was able to keep a job. The death

of his Father when he was nine years old made his going to work an absolute

necessity. He had also lost an older sister, Irene, to tuberculosis. She

was seventeen. Safrit's Mother never remarried, so James Safrit had to

become a major breadwinner for the family, which consisted of younger

brother, J.W. and younger sister, Lula.

Safrit was a very good athlete and was playing semi-pro baseball with

adult teams by the time he was in his mid-teens. The fact that he was

no longer in school during his teen years did not prevent him from playing

football at the Farm Life High School in China Grove. At that time, eligibility

rules were very lax and he was able to take advantage of that laxness

and play some football at the school.

|

The United States Congress created

the first peacetime draft in American History in 1940 in order to begin

getting ready "just in case" we got drug into the war in Europe.

James Safrit volunteered through the Selective Service System and entered

the US Army on January 22, 1941. He received basic training and participated

in major maneuvers or war games in Tennessee and in the Carolinas during

1941, and then was transferred to the inactive enlisted reserve corps

on November 4, 1941. His inactive status didn't last long. On December

7, 1941, the Japanese attacked the US Naval Base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

The United States was suddenly at war in the Pacific and in Europe. Safrit

was soon called back to active duty.

In January 1943, Safrit found himself in North Africa preparing for combat.

That is where he apparently began a journal that detailed his combat experiences

in North Africa, and Italy during 1943-44 as an infantryman in the 45th

"Thunderbird" Division. He also served in the Sicily campaign,

but makes no mention of it in his journal.

North Africa

I joined the 41st Armored Infantry, Co. E, 2nd Armored Division on January

23, 1943. We were deep in the "Cork Forest", northeast of Rabat,

Morocco, where we began intensive training for combat.

On February 6, we were part of a naval convoy heading toward Casablanca.

Our convoy continued on with little gray destroyers darting here and there

dropping countless depth charges. During the night, we were again attacked

by subs. We lay breathless below decks waiting for suspense filled hours

for those slim little pencils of death, the torpedoes, to blow our ship

to hell. Finally, they were away and the all clear was sounded.

On February 9, we sailed into the harbor of Casablanca. We wove our way

through mine fields and sunken hulks of French naval ships, sunk by our

navy in the initial assault on North Africa. We passed within a few yards

of the mightiest battleship of the French fleet, the Jean Bart, sunk by

navy planes and the powerful guns of our battleship Massachusetts.

|

|

A 40&8

box car

|

Later in February, we moved from

Casablanca, North Africa to Oran, French Morocco by French type 40 + 8 boxcars,

which were designed to carry 40 men or 8 horses. There were 43 men plus

full field packs jammed into that small space.

My buddy and I managed to get the space at the door, which provided us

with free movement, and we could dangle our feet over the side and enjoy

the scenery. That was just swell until night fell and we started looking

for a place to sleep. The only way was to sit up straight and try to sleep,

hopefully without falling out the door.

Sometime during the night, I must have just tumbled out, because, about

a week later, I came to in the 52nd Station Hospital with a fractured

skull, broken jaw, dislocated shoulder, and was bruised and skinned from

head to foot.

The nurse told me that an Arab had brought me to the MP station draped

across a donkey. They figured I was going to cash in because they had

me in the emergency ward all by myself. The Doc said I had retrograde

amnesia, or temporary loss of memory. I just can't figure out what happened

after I fell out of the train until I came around in the hospital. All

I know is that I kept dreaming about being bounced up and down, and a

strange, weird chant kept humming in my brain, which must have been the

Arab singing some Moslem or Mohammedan Death Chant. I just thank God that

he didn't leave me in the desert. I would have been buzzard bait in no

time at all. I hope Allah was good to that Arab, because I certainly owed

my life to him.

[editor's

note: It is unclear as to when James Safrit arrived at the 179th Regiment

possibly as a replacement at the end of the Sicily campaign]

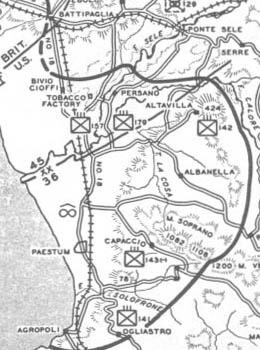

Salerno

|

|

11

Sept 43 Italy

|

Salerno Beachhead: September,

1943

The first few days of this operation

became a nightmare of exploding shells, of moving here and digging in,

then suddenly up and moving again, and doing that over and over again.

They say we were surrounded for 8 or 9 days and that one time they had

started to load us back on the boats and evacuate us, but after a while,

things became partly normal, if there is such a thing in combat.

Anyway, we began to chase the

"Jerries" into the hills a little at a time. They certainly

weren't in a hurry. When we attacked and took a stinking little Italian

town, after fighting from house to house, the Germans would counterattack

and run us out again. Then we would have to do it all over again.

Later in September:

Last night, or early this morning,

I was sent on patrol for the first time. It was a recon job to report

the effect of a particularly vicious artillery barrage the 160th Field

Artillery had thrown on a group of Germans they had caught in the open.

There were 5 or 6 of us with a lieutenant in charge. We crossed a small

stream to a farmhouse and stayed until daybreak. We had noticed a terrible

odor for some time, and, when daylight came, we found out what it was.

About a hundred yards from the house, there was a sickening jumble of

what had once been men. But now, there was nothing but blasted bits of

flesh. Arms and legs were everywhere. One lower torso of a German soldier

was sitting on the ground, and the upper half, what was left, had been

blown crazily to one side, still attached to a slender thread of flesh.

If I live to be a hundred, I'll never see anything to match such ghastly

horror.

The lieutenant, with his face as white as a sheet, obediently went around

counting arms and legs until he could report how many casualties the Germans

had suffered. Apparently, the "Divarty" guys had caught a platoon

in marching formation and just brought their fire down in the middle of

them. They never knew what hit them. Divarty must have continued to fire

into the corpses.

When we got back to the regimental command post (CP), the lieutenant told

the colonel he had counted 28 dead and arms and legs enough for ten and

a half more. My first patrol was certainly one I'll never forget.

That same day, Francis Burns, nicknamed "Buddy", joined us as

a replacement. He was assigned to our squad as a 2nd scout. Since I was

1st scout, I tried to trade places with him, but "No dice",

he said. His mother taught him to be polite and never walk in front of

other people. This character was quite a kidder. As time went by, we became

inseparable. We went everywhere together; dug our holes together; and

when things got hot, we prayed together. He never failed to amaze me by

being so cool, calm, and collected. After every murderous artillery barrage

the Germans threw at us, he seemed to shake off the terror, fear, and

wonder that possesses a soldier after he has undergone such a horrible

ordeal and finds that he is still alive. It never seemed to affect him

like it did me. It left a feeling of foreboding doom in me. I lived under

a constant cloud of fear and anxiety. I became nervous and jumpy, and

the slightest sound made me alert. Perhaps

my fear gave me a sort of sixth sense. It made my mind sharp and clear

to every lurking danger. On more than one occasion, it probably saved

my life.

|

|

179th crosses Volturno

river Nov. 43

|

One day, while advancing up a

hill toward Venafro, and just before reaching the crest, I turned and

signaled the squad to halt until I could reconnoiter. I had just turned

to move when the bump on my head, which I had gotten when I fell out of

the train in North Africa, began to pound like a trip hammer. The next

thing I knew, I had hit the ground and started to roll like crazy. Even

as I hit the ground, I heard the splitting snarl of bullets whine all

around, and while I tried to roll behind a stone wall, that machine-gun

began to traverse and track me to the wall I finally rolled behind. When

my senses cleared, I found that I was sweating like a horse. I must have

been as white as a sheet, because I sure was scared stiff. In my mind,

I'm convinced that I dove for the ground before I heard that machine-gun

open up.

The rest of the squad closed

in and somebody threw a grenade into the German bunker. That took care

of that. There were three of them. One was wounded and two were what we

considered to be very good Germans-the dead kind. Strange that I had not

seen that bunker, but somehow I had sensed it. The wounded one came out

yelling, "Komerade, no shoot poor Polock!" A lot of Polish soldiers

were being forced to fight by the Germans, and many would give up the

first chance that they got, but this particular one was obviously no "Polock."

He was a real typical Nazi. Blond, with an arrogant half sneer on his

lips, he was just using that "poor Polock" routine to save his

own skin.One of our guys

had been cut to pieces by a burst from this bastard's machine-gun and

he expected mercy.

The lieutenant came up and slapped the hell out of the prisoner. Then

he ordered a Polish refugee that we had in our squad to come up. This

guy had lost his mother and father when the Germans invaded Poland in

1939, and he hated them with a soul consuming passion. The lieutenant

said to him, "Take this 'squarehead' back to Battalion HQ, and be

back here in 15 minutes." The Pole knew what he meant. We all knew

what he meant. It would take him at least an hour and a half to get to

HQ, and back, down the tortuous mountain trail which was under mortar

and artillery fire. He just jabbed the Kraut with his bayonet and said

something to him in German, and they moved off down the trail. About 5

minutes later, a shot rang out and pretty soon "Jag" came back

with the funniest look in his eyes I have ever seen. It was just as if

I had gazed into the eyes of Satan himself. The lieutenant just said,

"What took you so long, Jaggy?" I have wondered how anyone could

feel such hatred as I saw in Jaggy's eyes. But I suppose if my parents

had been killed like his were, I would feel the same way.

Burns told me why he doesn't

let this war get him down like it does the other guys and me. Believe

it or not, he had the almost childlike conviction that his grandmother

was psychic, or able to tell the future. He named many instances where

she had proved uncannily correct in her predictions. Darned if he hasn't

got me believing it. She told him that he would go through the war without

a scratch, and he firmly believed it. He was just as scared as anyone

else while the shells, bullets, and bombs were raining down. But the minute

it was over, he would start wisecracking in that screwball Donald Duck

falsetto voice of his, and so help me, he could even make me or anybody

else laugh. He would kid me about looking so grim. After a particularly

heavy barrage was over, I would start feeling myself all over to see if

I was hit, and he would say, "Hell, Rebel, quit dreaming about getting

a 'blighty.'" You're going to spend 10 more years in Italy dodging

those 88's." A "blighty" is what a "limey" (British

soldier) calls a wound that's not too bad, but still bad enough to get

you sent home.

|

|

Varga

Pin Up © Hearst 1943

|

Burns and I could say anything

to each other and not get sore. He had a button nose like Bob Hope. I

used to tell him I would give my right arm if I could wake up some morning

and find out that he was a beautiful woman instead of a homely Yankee

bastard, and he would start talking like a dame. Burns could imitate anybody.

He kept us entertained with his imitations of movie stars. He was one

regular guy.

We are beginning to hit Hitler's

Winter Line, and it rains every day. The ground is a sea of mud and the

mountains are getting steeper all the time--and the Krauts are getting

tougher. We measure our gains by yards, and every inch is fought for with

"blood, sweat, and tears."

We are bombed and strafed by Fock Wulf 190s, ME-109s, and 111s often,

mostly at night. They drop flares and buzz around all night dropping "butterfly"

bombs and strafing. The sky is filled with tracer bullets and he muffled

"whoomp" of the "ack-ack" shells. There's no sleeping

here. Now and then we see a ball of fire gliding earthward and we have

the satisfaction of knowing that our ack-ack doesn't always miss.

Sometimes I think the worst part of combat is the endless waiting, waiting-just

thinking about home, hoping we'll get relieved, yet knowing darned well

we won't. We spend waiting time listening to the endless rumors that the

fellows make up just to relieve the monotony. Sometimes we start rumors

of our own. If a guy could turn his mind off and on like a light bulb,

war wouldn't be quite so bad, or if he could just force his brain to think

of the past, of pleasant things, and never think of what may happen when

the next attack comes, it still wouldn't be so bad.

|

|

Nebelwerfer-41,

6 barrel mortar

"screaming meemies"

|

Those 88s [editor

note:in talking to vets every piece of artillery is the famous "88"

even if it was a different type of artillery] and "screaming

meemies" come in as if they were ordered up on schedule, which they

are. I have begun to believe that the bastard who invented the 88s designed

it especially to torment our souls, which there is no doubt of. Man, they

are wicked!

We hear that old "Schicklgruber"

has ordered the Krauts to hold this Winter Line, as they call it, all

winter, and they certainly intend to do it. Every pillbox is a veritable

fortress, dug deep into the ground and covered with steel bars or thick

logs that only a direct hit by a 150 mm shell will knock out.

We captured some that had everything in them, including women's slips,

dresses, stockings, and panties, as well as all sorts of delicious food

and plenty of "Schnapps", or German whiskey. We especially enjoyed

liberating that.

The only way we can advance is for the artillery to pound the hell out

of the Germans, and then we move up as close as possible. When the barrage

lifts, we move in and quickly toss grenades into the gun slits. Each one

of those pillboxes is covered by the machine-guns of others. Man, I've

learned to crawl like a snake! I have had plenty of spent bullets and

shrapnel to slap into me. I would welcome a small wound just to get back

to a hospital and take a bath. I don't feel sorry for anybody who gets

hit, no matter how bad; at least they are out of it. That's more than

I can say. Gee, you should see the relief on the faces of those who are

heading to the hospitals.

An ordinary civilian could never understand how a man feels who has been

through hell, beaten down, knowing fear in his heart countless times;

a man who has forced himself to do a task while his mind and soul are

screaming for him to turn around and run, and never stop running until

he is safe at home in his mother's arms, like he did when he was a child.

But a man with any self respect can't do that and still live with himself,

so he just keeps plugging along.

Many times I imagined how it might happen, how I might get out of this

hell: Suddenly, unexpectedly, there's this ripping burst of machine-gun

fire, or an explosion that comes out of nowhere, then a searing, burning

pain. A feeling of panic and shock hits your brain, and you realize that

what you have secretly hoped for has happened. You have been wounded,

how bad doesn't matter. All you care is that you have been honorably relieved

from this hell on earth. Nobody can keep you here any longer. A fierce

pride floods through you, and calmly, you wait for the medic to take you

away. Other guys pass you moving up. They envy you and you can feel it….At

least that is the way I would feel.

|

|

Mule

train near Venafro, Italy

|

We have crossed the Volturno

River, taken Venafro, Pozzilli, and Piedmonte De Alife. Every inch has

been paid for in blood. Our casualties have been heavy. Men come and go

so fast, I never even learn their names. An old friend I met in North

Africa, Carl Smithers, turned up as a replacement. We had a lot of fun

recalling the times we had in Casablanca.

We were in battalion reserve at the time we met again, and we were detailed

that same night to unload some mules that were used to carry supplies

up the mountains to the front-line troops. The mountain trails were so

rugged that the mules go only as far as they can, and we lug the supplies

the rest of the way. There were 14 of us, including Smithers, detailed

to carry K-rations, mortar shells in clover cases, grenades, etc. We had

just reached "G" Company CP when the krauts threw a terrific

mortar barrage into the CP area. When it was over, we found two dead and

four wounded. Smithers was hit bad, a big hole in his stomach and blood

oozed from his chest.

The rest of us were assigned the unpleasant task of carrying the wounded

down the mountain to the Battalion Aid Station. I helped to carry Smithers.

He was conscious and asked for a cigarette, so I threw a raincoat over

us and lit one. He took a deep drag into his tortured lungs. I knew he

was dying and, for the life of me, I couldn't refuse his last request.

By then, the Germans were dropping mortar shells along the trail, so we

were forced to set the stretchers down many times and hug the ground.

By the time we reached the base of the mountain, Smithers had begun to

rattle horribly in his chest. Just before we reached the aid station,

he gave a long, tortured sigh and never uttered another sound. Another

good guy "gone west." He had traveled 4,000 miles to die on

a muddy stinking hill on his very first day of combat with no one to comfort

him or really care, but such is war. You just can't dwell on a friend

getting killed. If you do, it will drive you stark raving mad. Death was

nothing new to me by then, but seeing a buddy go like that with only a

few hours of combat behind him made me realize even more how close and

how quickly the "Grim Reaper" could snuff out your life. One

minute full of vibrant healthy life, and the next, a misshapen lifeless

hulk that seems to shrink after life has fled from the body.

Burns has gone to Naples to

the rest center. A few out of each platoon go every week for 6 days. I

just hope I don't get knocked off before my 6 days of rest come up.

The sergeant gave me a new man to team up with. Now I know why the old

timers are leery of rookies. Hell, this guy could get me killed! He won't

listen to the little advice I can offer. Guess he will have to learn the

hard way. He wants to be a hero and win this war all by himself. I'm no

damn hero. I just want to stay alive. We are going to make a push at dawn,

so we'll see how brave this cocky fella is.

We sleep two hours and stand guard two hours. This jerk ran the watch

up and I got cheated out of most of my sleeping time. I didn't know it

until I checked with the sergeant. I found my new foxhole mate had run

the watch up an hour and ten minutes. I went back to the hole and snatched

him out and knocked the hell out of him. How can you trust a guy like

that with your life?

After the attack pushed off,

our objective was another lousy, bald headed, rocky hill with a number

I can't remember. We gained the crest after a hell of a battle through

shells, bullets, and S Mines, or "Bouncing Betty" mines. When

you unwittingly step on them, they bounce about four feet and explode,

showering little balls everywhere. All the approaches to the German positions

are zeroed in with artillery, mortars, and machine-guns. The narrow trails

are sewn with concealed mines attached to thin, hard to see, trip wires.

God, you have to be careful! One misstep can be your last, and to add

to the difficulty of detecting those fiendish mines, those square-headed

bastards are trying to kill us with everything else they can lay their

hands on.

This particular hill had only a small rear guard to oppose us, with the

main enemy force pulling back to new positions. After we had mopped up,

and our dead and wounded were carried away, we dug in to await the usual

counter attack that always followed one of ours. My new second scout finally

showed up. I hadn't seen him since the attack pushed off. He said the

lieutenant had made a runner out of him. I'm wondering….

That night, we sat huddled in our slit trench with the rain beating down

on us in torrents. About 0300, it suddenly let up. Everything across the

way in Hun land was as quiet as a tomb. We knew from past experience that

when the Krauts were still, something was brewing-that Hell was ready

to spew over.

We didn't have long to wait. About 0500, from out of the fog shrouded

half light of dawn came the flashing flame of those dreaded 88s, and heavier

artillery zeroed in on our line of holes dug in along an old Roman stone

wall. The buzzing, ripping sound of flying shrapnel mingled with the screaming

and wailing of 88s and Nebelwerfer mortars. The ripping "whoomp"

of aerial bursts added to the maelstrom. A thousand years later, it seemed,

in reality, only minutes, the barrage lifted and a flight of Focke Wulfs

roared in and bombed and strafed our suffering little plot of Hell. All

the while, the two of us lay huddled in our shallow little hole and prayed

with every breath. I finally realized that we both were screaming like

madmen to release the pent up fear and emotion inside our terrified souls.

Suddenly, there was a terrific explosion and it seemed as if a giant hand

had grabbed me by the neck and jerked me out of the hole and shook me

like a rag doll. My ears rang like a doorbell, and blood ran into my mouth

from my nose. In my stunned mind, I thought, "This is it. I've finally

gotten the direct hit I've been expecting for so long."

A million things flashed through my mind. I suddenly felt panic stricken.

I kept hearing myself saying over and over, "Oh God, Mom! Mom!"

I tried to say something else, but I couldn't get my brain off those four

words. I felt like a helpless child seeking comfort and shelter from my

mother's arms, but she wasn't there, and in my stunned condition, I couldn't

grasp that fact. I just kept calling her. I know it is silly, but I just

couldn't help it. I kept thinking how lonely it would be to die so far

from home.

Finally, my head cleared and I calmed down. I started talking to the kid

beside me, but he didn't answer. I shook him and turned him over and eyes

gazed at me with an empty, glassy stare. His mouth hung open as if he

had started to speak and it had frozen. Then I knew he was dead. I screamed

for a medic, but there was none around. Even if there had been, he couldn't

have helped him.

|

|

60 mm mortar

|

By now, the Germans were sweeping

across the narrow valley floor heading for our hill. They were too close

for our artillery to be used effectively, but our 60 and 80 mm's [mortars]

were beginning to find the range and, together with the stutter of the

machine-guns, the line of Krauts began to falter, but, as fast as they

fell, another wave would take their place.

The Kraut medics would carry

supposedly wounded men as close to our positions as possible, hoping we

would not fire on them. Suddenly, those "patients" would spring

off the stretchers and come charging toward us with a burp gun spitting

in their hands. The Polish guy in the next hole was sprawled across a

boulder squeezing off shots as unconcernedly as if he was at a shooting

gallery back in the states.

By this time, the Krauts were all over the place. Sergeant Kronie came

charging up with a squad of guys I'd never seen before. I found out later

that they were strays from other companies in the Battalion he had gotten

together. He was roaring, "All right, you guys, fix bayonets! We

are going to run those Kraut-eating bastards clear back to Berlin."

Most of us figured it was better to chase Germans than to have that crazy

Indian put us on his "s--- list", so we rammed our bayonets

on and took off. That shiny cold steel must have been too much for the

"Square heads" to stomach, for it wasn't long until they were

running like hell back where they came from. One tripped on his long overcoat,

or maybe a rock, and fell headlong in front of me. He rolled over and

started to pull himself up. In one hand, he held a trench knife. But he

was just too damned slow. My bayonet went clear through his guts. When

it came out, it squished. After it was all over, and I had time to think

about it, I got knots in my stomach and I felt like throwing up.

We kept going until we hit a minefield, and then the Germans started a

counterattack with artillery and mortars, so we had to pull back to our

previous positions.

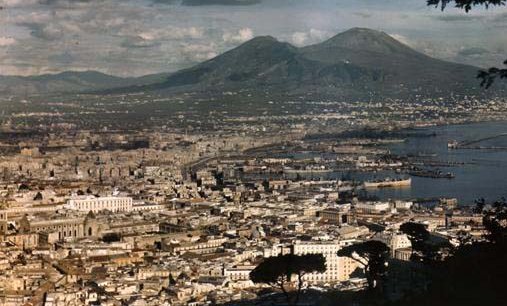

A few days later, I and a couple of other guys were sent to Naples for

a long awaited six-day rest. Gee, it was just like heaven, being clean

again, nothing to worry about but eat, sleep, and go to town. We took

in all the spots along the Via Roma, Naple's main drag, that weren't off

limits, and a lot that were. Those Italian gals leave nothing to be desired.

|

Naples,

Italy

The Melvin C. Shaffer Collection, World War II, 1939 - 1945

Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas; http://digitallibrary.smu.edu/

|

Six days in paradise went by

all too quickly. Burns is with me again, and I feel better with him around.

We went on a daylight patrol to find out where the main German line was

located. We moved out in a skirmish line. Burns and I were out as scouts.

Off to our left was a little knoll covered with brush and a couple of

trees. It was a swell spot for snipers or machine-gun positions, so Burns

swung around in back just in case. I kept moving cautiously forward. As

I moved up, I had the queerest sensation. I felt as if I was naked and

unwanted eyes were watching me. My head had that nervous twitch, too.

To be honest, I was just plain scared. I could almost feel hot slugs from

a sniper's rifle rip into me.

|

|

MP40-Schmeisser

machine pistol

|

I was so keyed up that, if I

heard the slightest sound, I would throw myself to the ground. I had crept

half way up the gently sloping knoll, when suddenly, not 20 feet in front

of me, a little fat guy, wearing thick lensed glasses and an overcoat

that hung down to his shoe tops, sprang up. When he did, his steel helmet

went flying off his head, hit a rock, and rolled crazily down toward my

feet. I was so startled that I was paralyzed. I couldn't move. The Kraut

was yelling, "No shoot! No shoot! Me good Polock! Me good Polock!"

He was pointing at an ugly looking machine pistol that was set up and

camouflaged so cleverly that I never would have seen it in a million years.

That was what was making me feel so strange when I was advancing toward

that spot.

When I snapped out of my shocked trance, I realized that he was pointing

the gun and saying, "Me no shoot you." He wanted to give himself

up. By this time, Burns appeared and sized up the situation. He walked

over and kicked the Schmeisser machine pistol down into the hole the enemy

soldier had been crouching in a few minutes before. Burns said, "It's

a damn good thing this guy was born a Polock, cause if he had been an

SS trooper, you and me would have been ganging on the Pearly Gates by

now." I certainly agreed. All he would have had to do was just squeeze

of a burst from that burp gun and we would never have known what hit us.

I murmured a prayer of thanks to God for letting him be an unwilling Pole

instead of a German.

After the squad came up, "Jag" started questioning him in Polish.

He said that the Germans had pulled back to new positions and had left

him and two others as a rear guard just to slow us down. He said he had

been wanting to surrender for a long time, but had never had a chance

until the other two guys skipped out. Holy Hannah!! No wonder scouts turn

gray headed so young and so quick. I wish I could get a promotion to the

rear ranks. Gray hair doesn't look good on me.

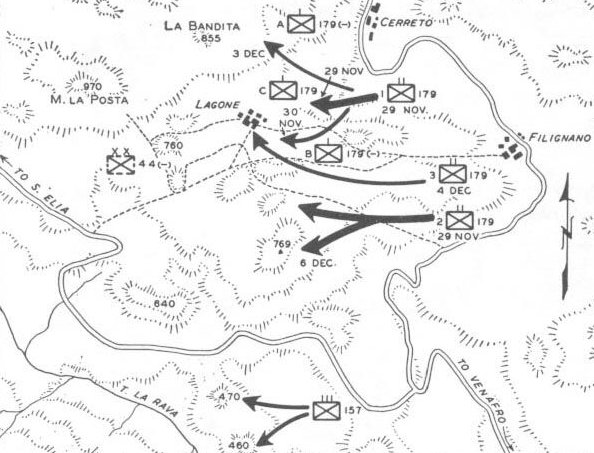

|

|

Capturing

Hill 769, Italy

|

Our regiment finally took Hill

769, a rocky, barren, treeless, shell blasted, saddle backed ridge lined

mountain with the little suffering towns of Filignano and Lagone nestling

at the base of it. Our first platoon is dug in on the shoulder of the

hill. We are the anchors of the company's perimeter. My squad has the

dubious duty of commanding the pass that runs between our Hill 769 and

Hill 759 to the left of us. This pass is the route the Krauts take to

pass behind our lines on their nightly patrols.

|

|

Hill

769

|

When night falls, a curtain of

dense fog envelops the pass, making it impossible to see two feet in front

of us. So, when it gets dark, a squad goes into the pass and lies in wait

for the Germans to come trough. Then we try to bushwhack them or get a

prisoner.

Many weird and eerie things have happened in this fog-shrouded basin.

One night, Jag was mumbling to himself in Polish, as he often did, while

he sat around waiting for something to happen. Suddenly, all hell broke

loose. He let out a shriek that echoed and reechoed all around the mountain.

His rifle started barking. We could tell it was his because the Kraut's

karbiner doesn't sound like ours. Then a burst from a machine pistol splattered

against the rocks. Immediately, we heard sounds of running feet and the

guttural sounds of German voices fade away toward enemy lines.

Jaggy told us later that he was talking to himself when a hand touched

him on the shoulder and a voice whispered to him in German. That is when

we heard that startled yell and the shots. Both were so startled that

their shots went wild. Apparently, the German patrol was sneaking through

and a Kraut heard him speaking Polish and mistook him for one of theirs.

That's one time I'm sure he was glad he didn't talk to himself in English.

If he had, his throat would have been cut from ear to ear.

There was another night when we had been on patrol and, on our way back,

we took a break in the basin before climbing up the hill to our positions.

When the Sarge gave the word to take a break, we flopped down in our tracks

dead tired. When I sat down, my hands touched something hard and rigid

and it felt like a rough cloth or canvas. A queer tingle raced up and

down my spine. I began to explore the thing with my hands. As my fingertips

slid along, I felt something sticky and revolting and jerked my hand away.

But my morbid curiosity got the best of me, so I began to explore downward

until I found a wire drawn tight around this thing. Finally, I felt the

leather boots and I realized I had sat down on the corpse of a German

soldier. The sticky mess I had touched was where his head should have

been, and as soon as I realized that, I let out a yelp of sheer horror.The

rest of the guys wanted to know what in hell was wrong. I was trying to

rub the nasty feeling off my hands in the dirt, and for months afterward,

I washed my hands every chance I got. Yet, I couldn't get them clean again.

It was too dark to see, but we could tell that it was a Kraut wrapped

in canvas and tied up with telephone wire that the Germans used. Everyone

surmised that an enemy patrol had been caught in an artillery barrage

and this guy had his head blown off. His buddies wrapped him up in a shelter-half

and were dragging him back to their lines to bury him when something prevented

them from finishing their grisly task. Perhaps, if we had looked around,

there might have been more bodies, but this one was quite enough.

It is beginning to snow on Hill

769 now. We are dug in behind a Roman stone wall. The holes are shallow

since the ground is too hard and rocky to dig deep, and we can't put shelter

halves up to protect us from the biting wind that whistles through the

pass, as the Jerries would spot them and drop mortar shells right in our

laps. My feet are so cold I can't even feel them. I take my boots off

every chance I get and rub my feet. Maybe that's why I haven't gotten

a real bad case of trench feet like a guy a few holes away. Last night,

he crawled down the mountain to the battalion aid station only to be sent

back up again. The poor kid is sobbing in frustrated anger, cursing the

medics for being so heartless. He feels that he should be in the hospital,

and no doubt he should, but they can't send us all to the hospital, so

they won't send him until they absolutely have to.

We lay there day after day sweating out the artillery barrages that come

so regularly that we know exactly when one is due. The company dwindles

down more and more every day. There are only about 42 men in the whole

company when there should be around 200.

A few nights ago, a guy in the

CP jumped in his hole when a shell came in and he dislodged the pin in

a grenade laying in the bottom of his hole. They could have picked him

up in a five-gallon bucket.

There are times when relieving

oneself proves to be a major problem. If the call of nature should come

at a time when the Krauts are throwing a barrage in, you throw modesty

to the winds. You just tell your foxhole mate to turn over while you use

a K-ration box for a commode. It's rather unpleasant, but it's better

than getting your head blown off. I've never heard of anyone complaining

while the other one is doing it. Perhaps he's too worried about the falling

shells to be concerned about something like that.

There are nights when the sky is cold and clear and the moon is full and

bright and you can see for miles. From my hole, I can turn my head and

look down into the cemetery far down the mountain. The little white crosses

stand out in the moon light like ghostly fingers beckoning to me. There

is a morbid fascination about them. I keep wondering, as all of us do,

if perhaps one of those crosses might not mark my own grave before another

night comes around.

Usually, we don't have to lay and contemplate our fate at night. There's

always the inevitable patrols sent out to prowl in "no man's land."

The Jerries are always uneasy, attested to by the fact that they are constantly

firing flares that light up everything as bright as day. I've learned

that when a flare catches you standing up you must freeze until it dies

out, because the slightest movement will attract a watchful eye and a

swarm of hot slugs. But if you stand perfectly still, those same eyes

may look straight at you and never see you. It's funny, but it's true.

We were sent into a village held by the Germans one night with orders

to fire a green flare if the village was occupied by a large force. I

think the high brass had planned to attack through the village if it was

lightly held. Anyway, when we reached the outskirts of the town, some

Kraut outpost challenged us. When we didn't answer, of course, they opened

fire and flares began going up all along the German front lines-bright

yellow flares that turned night into day.

The lieutenant led us up a hill overlooking the town and he fired a green

flare. Almost immediately, Germans started pouring out of houses all around

and yelling like crazy. The green flare was also a signal to our artillery,

which threw a tremendous barrage into those howling, screaming enemy troops.

Needless to say, we got the hell out fast, back to our lines. When the

attack swept through the next morning, it looked like a deadly cyclone

had ripped through it. German bodies were everywhere.

There's a rumor floating around that we are being relieved today. No one

believes it. Yet, about 1400, an order comes down that each squad is to

pull back at short intervals to avoid bunching up, and to assemble 1000

yards behind the lines. We are too tired and too cynical to register the

relief and joy that we all feel deep inside.

|