|

|

A

SOLDIER'S MEMOIR OF HIS WAR WWII; |

|

(Recalling the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor) We were at the movies, Ella and I, at the Leroy Theatre (just recently torn down, incidentally) and when we came out, the newspaper of the day showed pictures of the billowing smoke. I don't know how they got them over so fast. But anyway "Japanese Bomb Pearl Harbor". Roosevelt made his speech the next day. "A day that will live in infamy." When I was drafted into the army, they prepared me for Europe, it never made much sense to me, (fighting in Europe, rather than Japan) or anyone else. It never made any sense to the poor, battered bastards at Bastogne. But, in light of many years, we didn't have anything else, we didn't have enough troops either combined with the British or such allies as we had, and you'd hear people talking about how it was a United Nations decision. That's not so. The United Nations did not come into being until after the war.

I was drafted... I fought and I fought, but I had to go anyway. The only thing I did is that I lied about my age so that I would get drafted when I did, with my colleagues who I went to school with. Because, with a January birthday, I skipped a class, I was older at the time. I told them I was born in 1919. I sweat that out. Mainly the reason I did that was that my father saved me, not from a fate worse than death, but I guess I appreciated it in retrospect. He was a World War I vet. I wanted to join the Marines, in a big blush of...you know. He said, "Louis, I don't want you to join the Marines. They'll come and get you soon enough." He said, "If you join the Marines, I won't write to you." So I abandoned my idea of joining the Marines. And I'm happy that I did. They were not my cup of tea even then.

I entered the Army of the United States from Attleboro, MA, and was assigned to Fort Devens in Massachusetts for three days. I want to make some remarks about the Army of the United States. The Army of the United States represented either National Guardsmen or draftees, also in opposition or opposed to the United States Army. In my memory, we had 2 members of Company G at one time or another who were USA, United States Army. We had a soldier of many ranks whose name was Johnny J. Malish, and he will occur later in this document. We also had a captain, Capt. Walker who was West Point and United States Army, and I will relay an adventure that happened in the landings in France. As I recall, when they would read off the payroll, in Fort Devens and elsewhere, that the name that led all the rest was Malish, Johnny J. He got paid first, no matter what his rank was at the time, he got paid first. Because he was United States Army, the rest of us were Army of the United States. A fine distinction, and it meant alot if someone were seeking higher promotion that they, the regulars sure had the look-in. And we even said later as we became civilians once more, that it was a very embarrassing situation when the Korean War came along, because imagine, the Regular Army had to fight! There was no one else, and that's true.

I was the first of my two brothers to go in the service on Valentine's Day, 1942, which was very shortly after Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941. I got chided by my older brother, he said "Boy, were you tough." (regarding my stoic goodbyes). When the great day came, I had ordered a great bunch of roses for Ella to be delivered sometime Valentine's Day. My sister-in-law to be was driving Ella's mother's car. She picked me up at my house in South Attleboro. I said good-bye to the folks, and walked out of the house. Climbed in the car, and off we went to Attleboro, MA. I was dropped off at the Court House where we were formed into a group of about 14 people.

|

I met and became friendly with Bradford E. Tyndall and we were sitting on the train together, headed for Boston, South Station. So we got to South Station, and our group leader was an Attleboro young man named Maigret. He was extremely nervous and very conscious of his responsibilities of being a group leader of 14 or so people. So Tyndall and I went into the bar at the Hotel Manger. Hotel Manger and South Station, incidentally was the old Celtics arena. We were sitting there enjoying a whiskey and a beer and Mother Maigret came in all excited , "the train is ready for us." We had to transfer from South Station to North Station for entrainment to Fort Devens. "It will wait for us" we said. We kind of took our time, but then off we went to Fort Devens. We were all separated there. We were only there three days anyway.

My older brother Jim came down a week after me, and landed and trained at the same place, landed in the same Division, only he was assigned to the 179th Infantry (a part of the 45th Division). I was sent to Camp Croft, South Carolina for fourteen weeks of infantry training. The nearest town to Camp Croft was Spartanburg, but Greenville was a prettier, and friendlier town. I left Camp Croft in mid-May of 1942 and was sent back to Fort Devens, MA for further training and assignment to G Company, 157th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Division. Training, garrison duty...Oh happy days! Home almost every weekend until November of 1942. It felt like we would be at Devens forever. I'm not sure about how I asked Ella to marry me. I had said earlier that I thought I was going to be at Fort Devens forever. I was going home almost every weekend, unless I got a duty that I couldn't shake. It was just almost like living garrison life. Peacetime army, where Wednesday was always a half-holiday. So, we had it made in the shade, and yet the training was difficult.

We were taking basic infantry training all over again. You know, firing mortars, qualifying once again on the rifle range, that kind of thing, but nevertheless always in back of this was the thought that this was Fort Devens. Heck, you could take off from there and go to Boston and soldiers just fanned out. They went to Fitchburg and Lunenburg and Ayer. Ayer was a railroad station and two houses, but nevertheless, it was a beautiful post, I suppose. You might as well get married. And, it seemed like a good idea at the time. And then, having gotten married on the briefest of furloughs, actually, it was a three day pass, because Sat. and Sun. we got the time off, so what I got was Mon., Tues., and Weds. as a furlough. Starting Weds., in reverse, so I had to report back for duty on the Monday. With the admonition, "You'd better be there." And no idea that we were moving out. No idea at all that we were moving out to Pine Camp at the time, now Camp Drum. So that was quite a shock.

My sweetheart Ella N. Lacroix and I decided to wed. Five day furlough, wedding breakfast at Al's Ice Cream Shop, Central Falls, RI. Brief honeymoon, back on Saturday (wedding was Wednesday). Reception Saturday night at St. Jean Baptiste Hall, Pawtucket RI. Huge affair, must have been a hundred guests. Even had a square dance caller or "quadrilles" as people of Canadian descent call them. Menu: beer, wine, soda and snacks. Monday morning, back to Fort Devens to find the Division had moved to Pine Camp, Watertown, New York (now Camp Drum). It is now used for National Guard training and home base of the 10th Mountain Troops. So much for my ideas of garrison life close to home.

I only managed to see your mother three or four times after that, after our honeymoon. I guess I saw your mother three or four times. Once at home around Christmastime, Christmas and New Year's on Baxter Street, and then I saw her, when we would get shipped to Camp Pickett eventually, and I would hire, along with my buddies, a local Virginia taxi, who, for the munificent sum of ninety bucks, would take us to Washington. They would get us there, and tell us that they would be there, at the railroad station at such and such a time, and you'd better be there, because they wouldn't wait, they would just go back home. Leaving there, many times, getting stopped for speeding by the local constabulary, and the cab driver would say he had no money, and hope that the soldiers would chip in to allay his fine. We'd say, "No, all we need is a telephone to call in that the cab driver's been arrested." So, they couldn't bleed us that way.

|

At Pine Camp for three months, trying to keep from freezing. Six feet of snow on the ground, temperatures falling to 50 degrees below zero. Winter training, Pine Camp. I don't know what we were getting ready for, because when we left there they found out it was impossible to train under those conditions. I can remember going for a trip around the camp looking at the various training grounds with Captain Bledsoe at the time, from Oklahoma. He said, "Wims, what are all those poles?" 30 ft. high lining the side of the roads. It was clear, the roads were clear, this was November. I said, "Captain, that's so they can find the road when the snow starts to fall." "You're kidding!" When we got to six feet and more on the ground, we were now confined to tunnels between the barracks and the mess hall and what other buildings were around for mostly lectures on aircraft identification, not much training. We could not maneuver. It was armor training there until they couldn't train due to the weather.

So, it seems logical that now it is a place for the regular army 10th Mountain Division, which incidentally, fought in Italy, to train - alot of snow, not many big hills but sufficient to use your downhill skis and so on. They were around, nowadays, Lake Placid which isn't that far away. It's some distance, but you've got trucks and movers. They could go and train with their skis, snowshoes and that kind of thing. They were still using it for troops of the National Guard to train in the summer for their two weeks. So, at the present moment, it is an active camp. But the regular army is now slimmed down to 2 Regiments and Brigades with not much more than a couple of battalions, in our day. To be fast, mobile, that kind of thing.

|

Bill

Mauldin, author of "Up Front", started his career in the 45th Division

in the 180th Infantry. He was drawing his cartoons when we were at Fort Devens,

also at Pine Camp, becoming more and more nationally recognized as time went on.

Whilst we were in Sicily, he was still with the 45th Division. Later he went to

the Army Times and then to national recognition. He won a Pulitzer Prize with

"Up Front". And later, "The Brass Ring" which outlines his

difficulties with General Patton. I was always an admirer of Bill Mauldin and

his sardonic sense of humor, for what that's worth. He was at Ft. Devens and Pine

Camp at the same time I was.

Shipped back down south to Camp Pickett,

Virginia for mountain training, amphibious training on the Chesapeake Bay. (Recalling

encountering the slang "SNAFU") I remember the Battalion Commander in

the States, when we invaded some landing in the Chesapeake, and he's talking to

our captain at the time, and this was Col. Preston J.C. Murphy, a colorful character,

and he says, "Well Tris, not too bad. It is no more "fouled" up

than usual." It just struck me funny the cool way he took this. Fouled up

- what are you gonna do?

I never really got a chance to say goodbye to Ella and I didn't want to tell her. This was the only time that we would part in New York that I would say, "Well, I'll see you next week." and I knew I wouldn't see her. So this is the only time I waited and watched her train pull out. I never said a word, I did not tell her that we were shipping out. The last time I saw her, I for sure knew I was shipping out. My friend Ted Davidson, our first killed in action, gave me, at his discretion, a three day pass to go to New York. He said, "I have to tell you this. If you don't get back, I will have to deny that I wrote the pass." Jeez, he'd lose all his stripes, he'd lose everything. I said, "I'll be back, Sarge." He said, "I know you will be." We got on well, he will forever be in my memory. He died when they blew the bridge short of Termini Imerisi.

|

USAT

Thomas Jefferson APA-30 |

From Camp Pickett I went to Camp Patrick Henry to be shipped overseas to North Africa. The troop ship I was on was the Thomas Jefferson, which was taken over. It was a cruise ship but was taken over by the Navy or the Army or whoever was in charge of transportation at the time, as a transport. An AK, which means attack, transport. We trained on these ships in the Chesapeake, assaulting various islands, and seeing how we could make out. The transports were relatively lightly armed, no main batteries but they did have 20 mm cannons that the sailors strapped themselves in. They were manned by the Coast Guard. We were aboard transports, combat loaded for house to house fighting training for a week. House to house training was done in the environs of Arzew and Mustagema. We took the Southern route across the Atlantic. We marveled at the flying fish with such beautiful colors, fleeing predators and our first sight of Gibraltar.

The trip from the US to Algiers took quite a while. You've got to include the Mediterranean trench, it was a five day hiatus that occurred while we were doing this house fighting. So, I would say, we left the States June the 21st, probably 8 to 9 days, going slowly, zig-zagging across the Southern Atlantic. Slow convoy, one ship could only make so many knots. It was crowded (on board ship) but not crowded with personnel, you know, there were Jeeps aboard and stuff like that. It was not too bad, you suffered in the chow line a little bit. We were a combat loaded ship, we were expected to fight, we weren't there to eat, but they did manage to serve us breakfast and lunch and dinner on the way over. It was not that bad. What was bad was when they got in to the Mediterranean, and they put out the paravanes to sweep for mines, paravanes trail from the bow of the ship. Like a cable or a chain, and the chain would move up and down across the knife edge of the bow. If you're inside the opposite side of that knife edge, it made a horrendous racket. Sleeping was impossible. Fortunately, it was warm and you'd head up for the upper deck and bunk out there, especially under the lifeboats and such.

As soon as I left home, (there were) no photos (taken) of me if I knew about it. The guys were always taking pictures...."hey, wanna take a picture?'' "no, no, that's alright." And I guess I picked up the superstition from the picture of the Red Baron. He had his picture taken, such a hero to the Germans in WW I, so he had his picture taken and was killed a short while after. So no pictures. An actual combat picture and say "yeah, that's me" that's fine, I had no control over it. Anything I had control over, wasn't much, but I was very superstitious about having my picture taken. And I didn't send home any of these records, you know, I couldn't do that because I couldn't see sending home a possible "voice from the grave". I couldn't do that. You've never seen the movie "GI Joe", guy's got a record and he's playing it over and over again, 45 rpm, and it's his son talking to him, "Daddy, Dad" Boy. You don't need that, you really don't need that. You've got enough to do and enough to think about.

Into the Mediterranean and into Oran Harbor, to anchor offshore from Mustagama and Arzew, Algeria. Unloaded into small boats to assault the beaches, moved quickly into Arzew. One of our seasick soldiers, Speedy Durham, was lying in the sand, staring at a pair of gleaming cavalry boots. They belonged to a very profane General Patton, who said, "Son, if this was ever real combat, you would be dead." Speedy's reply; "He'd be doing me a favor."

First signpost I saw marked the distance to Sidi Bel Abbes which called to mind my sixth grade foreign legion stories, Beau Geste. We completed our week's training, loaded back on our transports to sail to positions off Sicily. As we left the harbor at Oran, British battleships Warspite and Ajax, with crews in their white uniforms at the rail, bugles, voices calling out "Attention to port!" as they watched us as we sailed by. I still get goosebumps now fifty-four years later.

|

HMS

Warspite |

SICILY

|

While this was going on, Private Donahue landed in the water between the boat and the ship. He went completely underneath and came up on the other side of the small boat, and a Coast Guard sailor fished him out with a hook. He had on no equipment, nothing, no helmet, nothing, all his stuff was abandoned. So that's our first. There were troops drowned , but none from G Company. Donahue made it through the whole thing, but landed on the beach with nothing.

Donahue was a hot sketch. Donahue was the guy who, back in the states, in September during the Jewish High Holy Days, the Sgt. said, "Any of you Jewish members of Company G, you've got the day off, fall out...Not you Donahue!" He tended to be a comic, he fell out. So Donahue was famous to me.

No, I never got seasick on these landings, just queasy. Landing at 6:00AM, ten miles left of where we should be. An interesting thing is that the Coast Guard enlisted men that we trained with, the Navy called them the X Division - extraneous to running the ships, they were running the transports, that's what their job was, to run the small boats. But somewhere between shipping out and landing off the shores of Sicily, we had now a new X Division of enlisted men, Coast Guardsmen, that we hadn't worked with before, we had not trained with. And they had not trained with us. So we had some lack of experience in the crew that took us into shore, and that probably accounted for the fact that we landed miles away. But that's routine. The Army and the Navy, the services had a phrase "SNAFU" Situation Normal, All Fouled Up.

Capturing the town of Scoglitti, with twenty or thirty Italian soldiers plus their commanding General. He wanted to formally surrender his sword and his troops. We treated him rudely and left him and others for troops following us.

|

A ten mile trek along the beach where we eventually captured Comiso Airport, July 10, 1943. We were warned by headquarters that we could expect German airborne counterattack night of July 10, 1943. A bright, moonlight night, we could clearly see the planes as American C-47s, we withheld fire. For whatever reason, Navy vessels offshore began shooting them down. A clear disaster, friendly fire in action.

I will try to mitigate the disaster somewhat. We, American soldiers had aircraft identification, silhouettes, and could clearly see that they were American airplanes. Even though we had been warned, we could clearly see the planes as American C-47s. Jesus, it was awful. On our ten mile trek, to get to where we were supposed to be, we stayed right on the beach because the Navy was firing over our heads. The invasion of Sicily was called "Operation Husky". We came upon a burning plane, a C-47, with papers that had been thrown out with "Operation Husky" as the title. C-47s carried maybe fourteen men, I'm not clear about that. They had seats along the side, they would hook up to a static line and jump out one right after another from 800 feet. Those guys started jumping as the plane was going down. There weren't too many bodies on the planes, some were in the water, I'm sure.

How many were lost? They kept that a secret, and we didn't know. We knew they weren't Germans, we could recognize German planes. They had bombers that looked like British bombers, kind of ugly aircraft and ours were ugly. But I have another incident further on, so I am perhaps more forgiving than I should be. Because I'm sure the Navy was told to expect an airborne attack also by our intelligence. All the newest troops land in intelligence. Very seldom do you get anyone to volunteer to be in intelligence. No one, especially junior officers, wanted to serve in intelligence. It was not a rapid promotion path.

All of this was up to the night after the landing. We went in on the night of the 9th-10th, we climbed into small boats. And when we went, going south, passing the downed C-47, the Navy was firing over our heads - too close - til we got into the town of Scoglitti, and we did capture it. That was a pretty good deal, we finally got where we were supposed to be - a ten mile hike to the right got us to Comiso. Very eerie feelings in Comiso. I felt like I was out of time - or born out of time. Very weird. It was the surroundings, it was the ancient buildings, I mean Roman buildings, 2,000 year old buildings. Patton felt the same, he felt he had been there before. I didn't so much feel that way, but I had a very weird feeling. Especially around Comiso, I never noticed it anywhere else.

Around Comiso, you know "American initiative", we had plenty of that. The Italian Army and the Italian people, too, I guess, had a bunch of automobiles, old-fashioned automobiles with running boards. Mounted on the running boards would be three great big tanks, with either charcoal or something in them, making gas. The gas they would burn in the vehicle to make the vehicle go. So naturally, infantry guys don't want to walk if they can help it, so we took over all those vehicles that were running, or asked the Italians to start them up for us, and we were using them for general transportation. It looked like Cox's army, a rabble in motion. Higher Headquarters issued a command, "There will be no using of captured vehicles, even military vehicles." So that ended our adventure of being our own army, because we were gonna be motorized.

You can see Americans doing that. That's the way they are. Initiative. "I'm

in charge now". That's the one thing we had over the Germans. We didn't have

too many things over the Germans. The Germans were great fighters, but American

initiative in that respect, everyone wanted to be in charge, everybody wants to

be the boss. So if there's some way that this man's commanding position in the

terrain, whatever it was, "I'm in charge, let's go. Follow me." or whatever.

Where the Germans, if they lost their leaders, their Sergeants, Kaiser pushing

them up and all that, they didn't know what to do. It was unheard of for a German

private to say, "I'm gonna take over." At least up until that time.

I don't know how it became later, because looking back on some of the stuff that

Col. Foster [LTC Hugh Foster III U.S. Army Ret. recording

secretary of the 157th Infantry Regiment Association]has given me, interviews

with Germans, other young Germans who were very much highly intelligent, would

see that maybe he wouldn't take over, he'd follow his orders but certainly question

them if they seemed stupid to him. So, there was hope that they might break out

of that mold. But that is what I think beat the Germans more than anything else.

I saw the same thing happen as far as taking over without the proper rank.

|

We were covering Comiso Airport with squads out, stuff like that, and in came a German Fokker Wolf 190, which looked very much like an American aircraft, but some one of our riflemen shot it down. What a surprise. He (the German pilot) thought he was coming back to an airport that they controlled.

So we're still covering Comiso Airport, and they're getting organized - putting companies where they belonged. Paratroopers are running around to come in and join us with their stars and stripes on their shoulders (and we had the same thing). So eventually someone came along and picked up these prisoners. It had made the papers that Scoglitti was one of the first towns taken and Comiso Airport. So while we surrounded Comiso Airport, just holding position, in came a Spitfire, and we could recognize Spitfires as well as any other foreign aircraft. Our own P-51 looked like a Fokker Wolf, we had trouble with that. But the silhouette of a Spitfire, with its wide, oval wings was easily recognizable. Well, one of our BAR gunners took some shots with that auto rifle at the Spitfire. Another incident of "friendly fire". Our guys were not as familiar with British aircraft as they should have been. It was clear that it was a Spitfire to me. I'm not going to name the man who shot it down.

A Browning Automatic Rifle carries a clip of 30 rounds and standard practice was to tape two of them together upside down so that you could fire off 30 rounds, either automatic or semi-automatic, and then flip it over and fire some more. So a BAR was a par automatic weapon. A BAR was a light machine gun really, light in the respect that it only weighed twenty pounds, and you carry twenty pounds on your shoulder for awhile. It seemed like it was always the smallest man in the company that carried the BAR. That's what we had and a rifle platoon had 2 BARs or 3 depending on how the squad was organized (3 squads in a platoon). If it had 2 BARs, it also had one bazooka. Or it had one sniper rifle, which was a 1903 model Springfield with a telescopic sight on it. It fired a clip of five rounds, which could only be fired one at a time. Or, we carried an M-1 or Garand rifle, which carried a clip of 8 rounds, and you could fire those one at a time, and then it would go "spling" and the clip would go flying out. A fully loaded combat soldier carried perhaps eight clips in a standard belt, with two bandoleers cris-crossed around his neck. The bandoleers were made of cloth, cheap cloth and carried quite a few rounds. Foggy memory, won't tell me how many. They were heavy. An M-1 or Garand rifle was an excellent weapon. It would never jam, even if it got full of sand, it would fire just the same, as long as you got that bolt open to get a clip in there, it would fire. Springfields could jam, or someone might have fooled with it or you set it wrong and you could pull the bolt out and throw it over your shoulder without knowing it.

I might break now and explain the line-up at the time. World War II Divisions were square divisions. They consisted of four infantry regiments, separated into two brigades of a regiment each, plus artillery regiment. As far as we were concerned, the Army had completed the 45th Division's triangularization - we were now three regiments to a division, one Battalion of artillery for each regiment, and one battalion of artillery for the division, known as division artillery. To make that simple, I can remember a captain, of fond memory, telling me, "It's easy to remember, Louis; 2 or more companies make a battalion, 2 or more battalions make a regiment, 2 or more regiments make a brigade, or 2 or more regiments could make, indeed, a division."

So in splitting up and shortly before Pearl Harbor, December 7, the 45th Division consisted of; the 157th Infantry, the 158th Infantry, the 179th Infantry and the 180th Infantry, the 158th Field Artillery which was part of the 157th. I don't know the regiment of artillery which went with the 158th. The 158th was split away from the 45th Division and sent to the Pacific. They were known as the "Bushmasters", they were a separate combat regiment. The 179th and 180th formed a brigade of the 45th Division together with their 160th Field Artillery. Division Artillery was the 189th Field Artillery. The Artillery Batteries, in our case the 158th, had three battalions, and headquarters and service battalions. The 158th was assigned to the 157th, Battery A would be assigned, normally to the 1st Battalion of the 157th. 2nd Battalion of the 158th was assigned to the Second Battalion of the 157th. And Batteries E, F and one extra Battalion covering the Battalion from the 89th covering each of our Battalions. The difference being that the 158th, 160th and the 171stth had 105mm guns (approx. 5 inches). The Division Artillery, the 189th had 155mm howitzers (approx. 6 inches). Service batteries didn't always fire. Further back, further support was obtained by 240mm howitzers which could fire twenty miles or more. The 189th Field Artillery Howitzers wouldn't cover that far.

And as you might expect, the artillery usually lined up for combat far enough behind the fighting infantry so that their shells would cover the front of the infantry up to 1,000 yards out (in front of the infantry). And the division artillery would be further back, to take into account their greater range, they would also cover our front. So we had lots of artillery at our beck and call. The 240mm howitzers - the so-called "Long Toms" - could fire twenty miles, so naturally they were eighteen miles back. We weren't over-endowed with artillery that were close. And yet, in the Italian campaign and the Sicilian campaign, in very mountainous terrain, very often the supporting artillery would be very close behind us. And in some cases they had to engage in direct fire which means they were pointing their weapons straight at the on-coming enemy troops. And if the enemy had armor, it would hit the armor and, depending on the size of the armored vehicle, it would knock it out.

45th Division [National Guard]guys were replaced before I joined them by several batches from Wisconsin, Michigan, New York, New England and some southerners from West Virginia, Virginia, Alabama. Later in the war, when the Italian campaign was over for us, we were pretty homogenized. It was worthy of note that my friend Technical Sergeant Maurice Bierman was from Wisconsin, he had served with the 45th down south in Camp Barkley, Tx. I told him in 1970 that when all of G Company as it stood then, was captured at Riepertswiller, Sergeant Bierman and myself were the only two who had seen service with the 45th in the United States. Of the entire company we had 22 men walking away from there, maybe one or two more, but of all the troops captured, 5 companies, there were maybe 125 men. When you figure full strength of that many companies would be like a thousand men, we were pretty punched out at the time. Morale was terrible.

July 10, 1943 - We stayed in the environs of Comiso Airport for a day or so. During that time, someone shot down a German fighter plane, to the horrible surprise of the German pilot, who thought that the airport was still in German hands. Later the same day, a British Spitfire fighter was also shot down, leading to orders that planes were not to be fired on unless they committed a "hostile act". Sort of, "we will give you the first shot." This order led to one of Bill Mauldin's more famous cartoons, of a German fighter plane strafing, illustrated with black crosses all over the wings, there was no mistaking that this was a German fighter and Joe was telling Willy, "Make sure he commits a hostile act before you fire."

|

Within a day or two, we left the area of Comiso Airport, and started to attack across the island. Straight across the island in a northerly direction. We got as far as the big town of Caltanissetta, where, I guess, General Patton heard from General Montgomery of the British 8th Army, who was having difficulties around Catania and where the British had landed on the easterly side of the island. Informing Patton that the roadnet we were using belonged to the British and therefore, would we please get out of the way, because he needed that roadnet for his later plans. He kind of squeezed us out. So we fell back, all the way back to the beach, and then started to walk back across the island. Much unhappiness. Who am I to knock Generals? But, Patton was not very happy about that and being a very profane man, he made it known.

We were to cross a bridge heading toward Palermo. We were to cross that bridge when our lead troops were within forty paces. And this was a bridge with many arches, there was no water, nothing, and the Germans had it mined and they blew it up. The bridge went up as our lead man was about to put his foot on it. Boom! Holy mackerel! Good God! It blew up...you know, hell wouldn't have it. So that blocked our way toward Palermo. As the saying goes, "he was shaking with patriotism" when that thing went off. Whereupon, after the explosion, on the mountain, a German machine gun was set up, rear guard action. And he started firing on the road we were on. That's where we lost, to me, a beloved first sergeant, Ted Davison. He was a giant of a man. And when I speak of 1st Sgt. Davidson being a giant of a man I am not referring to his height, but his courage. Hit him in the head, and he never knew what hit him. His death was instantaneous. I can still see the German tracers which were greenish-white. I can see that bouncing off one of our soldiers helmets. Ricocheted, didn't kill him but put a hell of a dent. At the same time, that burst of fire killed the first sergeant.

Tracers are burning phosphorus. Their purpose was so you could see where your shots are going. It was tracer bullets, they didn't fire all tracers, it was every fifth round, was a tracer. You could see them, it was like, if they were off to one side, they were slow. They didn't go zip, they kind of fluttered over like a kid throwing a sparkler. Because what you're seeing is the burning, which of course occurs after. By and large, I don't know what color British tracers were, but I know German tracers were very bright greenish-white. American tracers were red. If you got hit by a tracer it would be a nastier wound, you'd get burned, but the tracer of itself wouldn't kill you. Depending on the round, if it were armor piercing, in many cases they were armor piercing, it would go through you so fast it would sear you, it might stop the bleeding. That might even be a possibility, depending on where it hit you, of course. We used tracers and we knew what our chances were. Most troops, I except myself in this case, were terrified of artillery. I was particularly terrified of small arms fire, you know, rifles, machine guns and like that. Because, you never would really hear the one that hit you. Where, the artillery, you could get a warning, hear the whistle. Even the 88's, you didn't get much warning on an 88. It was a question of what was more likely to kill you. More likely, I guess, small arms, where we were, forward troops.

Years later, I can remember going to a reunion and meeting a guy by the name of Carl Williams. He said, and these were the days where you talked, if you didn't like the first sergeant, somebody might take a shot at him, all that kind of stuff. And he implied that Ted Davidson got shot by his own men and I refused to talk to him. I said, "No, you are 100 % wrong, and I don't want to hear it. So, I don't remember you, but I know we transferred guys in and out, you could have been in the weapons platoon like you said you were, maybe Davidson gave you a hard time." He (Davidson) hated people who were AWOL, he was ready to fight you for that. But on the other hand, he gave me a three day pass and said. "Louis, if you don't come back, I'll deny I gave it to you." He exceeded his authority. That was the last time I saw Ella, incidentally.

After the bridge blew up, we took cover as best we could on the side of the slope. It was like four o'clock in the morning, and we're all laid down all around, and I got to thinking that we were on the wrong side of the slope. If the Germans were on the Palermo side, which we had every reason to believe that they were, when it came daylight we'd have no cover at all. I can remember, you know they say there comes a time when you know you're going to die for sure and comes anger, this, that and the other thing, comes total acceptance. I figured hey, it's all over. But no, as it happened, we didn't receive any fire from there and we stayed on our side, we could not go across the blown bridge. We went down a side road and went to the town of Termini Imerisi where we turned right and headed toward Cefalu. Then we began to run into resistance.

When our First Sergeant Davidson was killed, we did start to attack towards Cefalu and Termini Imerisi the next day. But the machine gun fire that killed Sergeant Davidson was manned by one German. We picked up this one German, and we were sending him back to the rear, chased by a soldier, and I won't name the soldier. He had his rifle, the guy (the prisoner) was running, his face dead white and scared, and he just got around out of sight, down the hill and we heard a shot. The man that was chasing, that's what we called it, chasing prisoners, came back and said, "He tried to escape, so I shot the son of a bitch." You know, I was horrified, and I am to this day. Good war, bad war. I didn't see him do it, but I sure heard him. You would not dispute it, but I didn't like that.

Initially we did not face much enemy fire upon landing in Sicily. The First Division encountered more resistance than we did. In our areas, as I told you, there were Italian troops defending, Coast Guard outfits. And they weren't much as a fighting outfit, they really weren't. So, I've taken you from the beach to Termini Imerisi and you saw what we ran into from there. The first time we encountered any amount of enemy fire would have been at the bridge and beyond. We operated from then on, in Sicily, going along the coastal road. General Bradley, God bless him, made us walk not on the road, but over the mountains. And Oh God, it was hard, exhausting.

We kept going until we came to, I don't remember the town, whether it was Cefalu or not, or beyond, but we came to another bridge that, as far as we knew was OK. So we're back on the road and we're gonna cross this bridge, and it turned out that we thought it might be heavily mined. The skipper (Battalion Commander) didn't want to wait. We continued to walk, and I don't know how it happened, but the front line troops in the column got across the bridge no sweat. Now it came to my outfit which normally, the approach march was what it was, brings up the rear of the column. Somebody stepped on a mine and it bounced up in the air, a "bouncing Betty" was what the Germans called it, with ball bearings. The executive officer of the Company was a Lt. Burns who was 6'6" or 6'7". In the normal course, I would walk behind him, but I wasn't with him. He was gravely wounded, but it didn't kill him because it hit him in the chest rather than the head. Sam Uretsky was killed, Davy Harris, another great friend of mine, was killed in the mine field. And then we waited for the, well the Colonel came along, and we waited for the mine sweepers to come up. And they swept 6,000 mines out from around the bridge. It was absolutely just luck that the first column made it across.

|

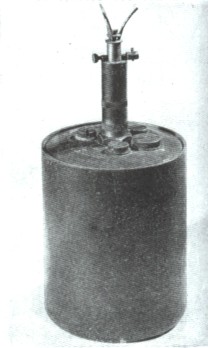

S

Mine 35 "Bouncing Betty" |

When we lost men, we didn't lose them to the teller going off, we lost them to the thing that bounced out of the teller, the bouncing betty. A canister of ball bearings jumped up in the air about four feet and exploded, throwing ball bearings in all directions. It caught Lt. Burns who was 6'6" tall, the only reason it didn't kill him was it hit him at chest level, but got no vital organs, I don't know how he survived. But poor Sam Uretsky was only 5 something and took the whole thing in the chest. Davy Harris was about 5'7" or 8, got it all in the chest. Terrible thing, I don't want to put my foot down. Spelled "Tellermine" [the teller mine was an anti-tank mine, the S mine (right) was the anti personel] like the famous physicist. Maybe it was named after the German who invented it, could be, I don't know.

The first column was probably a platoon. We were pretty strong so that probably was 30-40 men. Once the mines went off, everyone was afraid to move. Didn't want to sit down, didn't want to, you know, stand in place. And the mine sweepers did get up there and then we discovered later how many mines there were. Good God. The skipper got hell, and he shouldn't have. I don't know what lulled him into, you know, it's one thing when the bridge blew up, but this, you know, the bridge didn't blow up. It was just a nice area to stop people's progress. There was nowhere to go or go on the side of the hills and start all over again. And that's what we did the rest of the time. We didn't go very long, we went up in the hills and then we said, no, we've got to go around. It was getting towards the end of the Sicilian campaign which only lasted a total of 38 days.

The American army, and I guess many other armies too, but the American army had a fiendish idea of what kept you going forward. Let's say you left the United States. You left your base camp and it was kind of nice, hot shower and everything, kidding around with the guys, playing cards. And now the Division is going to move, or the Regiment is going to move, in my case, the Regiment, get down to the smallest unit. Approach march is let's say a company has 4 platoons, 3 rifle platoons, a weapons platoon and a headquarters section. And the approach march they will decide we're going to attack in column. The enemy's there somewhere so we're ready to fight and today the order of march will be 1st Platoon, 2nd Platoon, 3rd Platoon, Weapons, Headquarters. Well, you would hope that on this particular attack, maybe the 2nd Platoon would be second in line. These guys from the 1st Platoon, not that you had anything against them, but they took on the fire, and now you started to maneuver under fire. You always thought that.

The next day the order might be 2nd Platoon first, 3rd Platoon, Weapons, 1st Platoon in the rear. And maybe you got a chance to be further back. That was a fiendish way to keep troops in combat. There was always the chance that it wouldn't be you. Maybe my platoon won't be in the front, maybe in the rear. Even in the attacking platoon, maybe we'll be in reserve of the company, and we'll be in the rear, using us as necessary. That's the way the army operated. It was a very clever way to operate, very seldom did the army operate with say, two companies forward or two platoons forward and one in the back. Even the army didn't break up their divisions that way. They didn't want to commit, so you always wound up with just a few guys to initiate the combat, and it started to fall into place or whatever, for the manuevering. You didn't have to worry. They found the enemy and now you've got an advantage. You know at least where he is. Over there... you can't see him, but that's where he is. And that's the reason we always felt we'd get lucky and we wouldn't have to go. You know, we wouldn't have to go first. And of course the Germans, in many cases we did the same thing, would let you (first platoon) go, see what else you had.

You can understand it now, you'd say, well, maybe we'll luck out. You gotta hope for something. You knew you wouldn't stay in reserve the whole time. The idea of surviving certainly had to be being at the right place at the right time and not surviving was being in the wrong place at the right time, and everything hit you. The mines were the most terrifying thing, because it required no more enemy action. The enemy could be long gone. They don't even know you're getting blown up, but they know you haven't caught up with them yet. So, it must be doing some good. And that's why they started to get off, they figured the road could be easily mined and it was getting toward the end of the campaign, you could see the Germans were heading back, they weren't going to counter-attack anymore. So they were falling back and they got the idea to make an end run around them, and one of them was successful. So now Patton figured, let's have another one. Well Jeez, pretty soon, they're waiting for that.

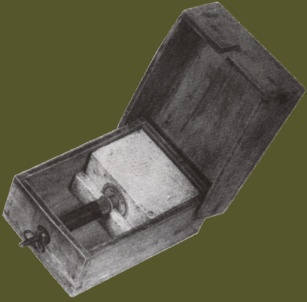

|

Wooden

mine 42 "Schu Mine" |

The tellermines were iron, or steel about a foot in diameter, and it was designed to disable tanks, blow them up. It required heavy pressure to set it off. But they could rig a tellermine with something on the top of it which took light pressure. The Germans put a mine, usually a tellermine, a big one, but on top of that, in the trigger mechanism they had a small cylinder that they put on top of a tellermine. So if light weight personnel like us stepped on this, a tank they didn't worry about, they figured if a tank ran over it, it would blow the tank up, the whole thing would go up. This thing would bounce up in the air about six foot high, and exploded like a hand grenade charge. Boy, it was deadly. They came out with one that wasn't a bouncing Betty, later, that was made of wood, like a cigar box with wooden hinges that couldn't be detected with a mine detector. On the breakout from Anzio, guys were stepping on those, blow their foot off. You can't go very far with no foot. They're deadly, mines are awful. They're scary, you don't know where they are.

We were on the road because we figured it was OK, they had moved on ahead, theoretically clearing out , "There's no Jerries here." So we continued that way along the coastal road until Patton got the great idea to "Let's have an amphibious landing behind the German line." And we, 2nd Battalion, drew the task of making this landing. So, that's when we got into Palermo, we went back to Palermo where they got the boats ready. We were certainly worried about this amphibious landing. You know, you can surprise them once, but, as it happened, we were very lucky that we made the landing and the 3rd Division, which was going along there, had massed there, had gone beyond. The first troops we saw there were 3rd Division troops. So, you know, good luck, right. This was now the rush to capture Messina. There was a big rush to capture Messina whether the British would capture it or we would capture it. And the British captured Messina, which was right across from Italy, two miles. Then we all fell back, to rest and take up positions, rest mostly. We were hearing all kinds of rumors that Mussolini was going to give up, there was all kinds of talk like that and we could see planes coming over with white markings, and they were not to be fired on. So this was emissaries from the Italians. We never did find out then what had happened.

We encountered civilians all the time on Sicily. We were nice to the Sicilians, or we tried to be, tried our Italian on them, "Buon Giorno". They were old-fashioned. Women, if they were widows, if they were 25 years old, they were wearing black. Life was over. Women were just good enough to go to church, you know, take care of that stuff. But the important stuff was taken care of by the men. Macho, that was Italian. And the same on the mainland, but we knew about Sicilian gangsters even then. Luciano, I guess, tried to make a deal with the United States, and I don't know whether he did, or not. I can't testify to that. He did, supposedly, give them information as to where the most resistance would be, or the least resistance. Maybe he did. Maybe he just told us that the most resistance was where the enemies' families lived. Like the Mafia in New York. They're tough guys. Some Italians would talk to you (if you greeted them) but they were quiet. They certainly didn't look on us as liberators by any stretch of the imagination. They just wanted to get rid of Mussolini, but at least he made the trains run on time. He got them on some kind of time. But he was bad news. That's when I began to see our own warts. This "good war", forget it. It wasn't a good war.

After a few days, I forget how many, now heading into the beginning of September, 1st - 8th of September, we're gonna go in reserve and invade Salerno. While we're on the boats, the transports, headed for Salerno, an announcement came over the radio, American news, that Mussolini had abdicated, or whatever and Italy had surrendered. Well, we figured it was gonna be a cakewalk. So did the 36th Division, who was in the assault landing, the 45th was in reserve. We landed some few days later. We landed, say, the 13th of September, the Salerno landing landed, say, September 9th. There was an MP directing traffic as we landed on the beach. We were gonna turn left, were supposed to turn left where the objectives were and so on. So we asked the MP, "What's happening?" He says, "We've got an army trapped up there. We've got a German army trapped up there." I'm thinking, "Well then, turn them loose!"

But it turned out that we were the rear battalion, 800-900 men, we were the reserve for the entire invasion. We were marching up this way and went, oh, can't go there, we went back and we were getting shell fire, we were getting airburst, it was terrible. Airbursts got so close to the ground, and would send a radio signal to the artillery shell and it blows up. They're the worst kind. It comes down on your head, you can't do anything. It goes off then, or if it hits something. Strange to say, most of our artillery experts, just figured where the ground was. We had airbursts, too, the first time we used them was at Riepertswiller, a designed airburst with radio control. They didn't figure on the height of the trees. The trees were 50-75 feet high. So, we were in heavy growth and they would go off over us instead of going over the Jerries where they were supposed to. At Salerno, no problem for the Germans if it was an airburst because there weren't any trees, there was a beach and not much there, except mountainous terrain.

The first battalion really got clobbered at Salerno, at Paestum. First Battalion artillery were firing direct fire, muzzle loaded, pointing at the enemy and firing. That's not supposed to happen in the artillery. Then came our friends in the Battleships Warspite and Achille and Ajax, firing their 14 inch guns and 16 inch guns. And the infantry would call back and say there's a German tank behind this house. They'd say "Where's the house?", look at the co-ordinates and blow the house down. Not many tanks are a match for a 16 inch gun. Together with the British battlewagons, we managed to at least secure the beach and save the day. They were seriously considering abandoning it and trying to get off. But then more troops started to come in and we began our march toward Naples.

|

HMS

Warspite |

Naples was the objective. To get there, we went into the mountains surrounding Naples. We marched through the town of Benevento. We had a Lt. Lemmon in the Battalion Headquarters, who was in the pioneer platoon. I can remember seeing this smoking rubble, and of course, we even had some rookies then, after the Sicilian campaign ended. He said, "Alright you guys, if you want to get tough, take a look at this." And you could see arms and legs sticking out of the smoking rubble. Jeez, you know, I thought, we weren't happy about that. That was Lt. Lemmon, and he will occur later in my story, in Anzio, I guess.

During lulls in the mountain fighting, up around Venafro in Italy, we were in the forward position, on the side of the mountain. And right now, no one was shooting at us, and we weren't shooting at anyone else, for the moment. We were in well, not really a foxhole, but we'd scrambled around, loosen up the rocks and kind of nestled down in there. And we also had, in the same area, back halfway down the mountain, into the valley, we had a rest area where the 105 mm artillery, the 158th Artillery was. That was our rest area. They would be firing at the Germans, and it wasn't very restful, but that's where it was. We were in a quiet moment discussing the possibility of what would make a "million dollar wound". To us a million dollar wound was something that would nick you bad enough where you could no longer serve as a front line soldier. We weren't looking to get out of the Army, we were just looking to get back to the rear and get away from all these guys shooting at us, which made us all extremely nervous. The bravest of us were extremely nervous, and I was never the bravest.

It was quite a serious topic of discussion because when we got to Venafro, we had been fighting for a long time, and we were already tired, not knowing that we had another year or so ahead of us. We didn't know that. And there were many times a guy would tell you quite honestly, "Boy, I got a million dollar wound." You know, maybe it damaged his eyes or his hand, or something like that. At the time it didn't look like much of a price to pay, a twisted hand, but it was. It was, because we had a man damaged in training, backfire from a bazooka, pieces of it landed in his eye, he lost his eye. He didn't get out of the army, he got out of combat, but he did not get out of the army. Bill Barrett served a long time before they discharged him. So even at that, most of us liked the army and the idea of a real million dollar wound was something that got you so they wouldn't use you in combat. You were bad news for combat. Soldiering, that wasn't too bad. Remember, there were 11 million armed forces guys, and there were about 2 million, maybe, if that, 10 percent of those were fighting men. The rest were support troops of whatever kind. Another job, load that , lift that bail, tote that barge, whatever, that kind of thing. You had to work anyway, we were young and strong, so that was a true million dollar wound.

To get off the line was miserable because if you got lightly wounded, they would patch you up, you know, requiring a few stitches, they would patch you up at the battalion aid station which was only 1,000 yards away, and send you back. So then, a more serious wound would require your evacuation back to a general hospital, where you needed a little more time. Well, that wasn't a million dollar wound either because they'd send you back from there. They'd send you to a replacement depot, in our case it was the 29th Repl Depl we called it, and you weren't guaranteed to be sent back to your own outfit. We raised merry hell about that. Because, can you imagine a soldier landing in another outfit? Where he doesn't know anybody. "I lost my home." He had guys who were dear friends of his and guys he didn't like at all, but they were his buddies. These are the guys he depended on and he knew they wouldn't shoot him. So it was very important, and it was Secretary of War Stimson's idea, tremendous idea, to keep troops in the line, in combat, until the unit in which he served was totally unrecognizable as a cohesive fighting force. And then you would get hauled off the line for a period of ten days or twelve days.

The one thing that you feared, was getting assigned to another outfit. So he'd leave you in the line and hopefully send you back to your own outfit. You used all the talking that you could when you got to Repl. Depo, say, "I'm in the 45th" you know because when you got a new uniform in the hospital, it had no patches or anything. You had no identifying feature. And the Repl. |

Harry

L. Stimson Secretary of War |

As far as saving lives, I don't know that it saved lives because you kept operating tireder and tireder soldiers. The morale of the guys you got, there's alot to the guys that hadn't really been shot at yet. They didn't know what the hell was gonna happen. You really couldn't tell them, 'cause the new fellas would ask you, "What's it like? What's combat like?" And I'd say, "Did you ever see an automobile accident when you were a kid?" "Yeah." "Did you know it was gonna happen?" "No." "Same thing." How could you explain it to them? You know, you're walking across a field, that's all you're doing, you're walking and looking, hunkering down. All of a sudden, zzzhou bang, you know, dddrrrrrr or whatever. You couldn't tell him. You could not tell him what to expect. Expecting it didn't make it any easier or like that. And pretty soon they were old-timers just like you. It only took ten days to be an old timer if you were still alive. But the first couple of days for a raw recruit who landed as a replacement, say at Anzio, or wherever, had to be God-awful. Had to be just awful.

My friend Clarence L. Staub, came from Wisconsin or Michigan - out that way, from the midwest. He was say, 5'9", stocky build, open face, very pleasant young man. I'm trying to think of what kind of wound I would take that would get me out and wouldn't hurt too much. "Then it becomes a discussion," he says "Would it be worth a leg?" I said, "No, not to me." A leg would hurt too much, and you might lay out there after your leg was gone and bleed to death anyway because there was nobody nearby. He said, "I think it would be worth a leg." So, sometime after that conversation, I don't know how long, we were engaged with the enemy, artillery and all kinds of stuff coming in and Clarence Staub got hit in the leg and lost his leg.

He sent me a letter when he slightly recovered, from the hospital, still in Italy in Caserta or Naples. He said, "well Lou, I have lost my leg." He said, "I'm not going to complain because I said it was worth it." He said, "I'll stand by that." It just broke me up. He was a nice guy, that's the kind of philosophy you get. But to be so sincere, with an ill considered remark on his part, that he thought it would be worth a leg, and I'm sure he was sincere when he said it. Not realizing the ramifications of loosing a leg, with the prosthetic devices available at the time. And then Clarence passed from my ken. In the 42 years it would've been difficult to get in touch with him and say "you were wrong". I often wondered what happened to him. He was probably a little bit younger than me. I was 23 so he was probably 21. But again, a nice young man, of which there were many, most of whom we left over there, and only we ugly ones like me came home.

I personally, was looking for a way out, an honorable way out, at the end of the war. I had my sources and my spies and my friends who were stationed further back than I was, like at battalion. And if any of those people got sent home, I wanted someone to put in a good word for me for their job. I probably would have made that had I survived Riepertswiller and one more battle.

It is interesting that my brother Jimmy was assigned to the 179th, and therefore part of my outfit, and my kid brother, I don't know how long after me and Jim, was assigned to the 83rd Chemical Battalion. They were going to fire gas shells or phosphorus shells or whatever from 4.2 inch mortars. He stayed there awhile and I figured, "that's pretty good, at least I got one guy who's at least as far back as the artillery." Well, it was soon decided, as the European war went on, that we'd still use 4.2 mortars, but we weren't planning on firing any poison gas. We would use them to fire smoke shells and white phosphorus, which was very deadly. It was like a smoke shell, however the sparks and stuff would continue to burn if it hit your clothing. But, I got a letter from my kid brother later on, saying he was transferred from the 83rd Chemical Battalion to the 10th Mountain Division which was serving in Europe at the time on the Southern front. But they were in our area, so I didn't feel very easy - having a brother who had been in a chemical battalion transferred out and now he's an infantryman with the 10th Mountain ski troops.

last revision