"A

SOLDIER'S MEMOIR OF HIS WAR WWII; |

|

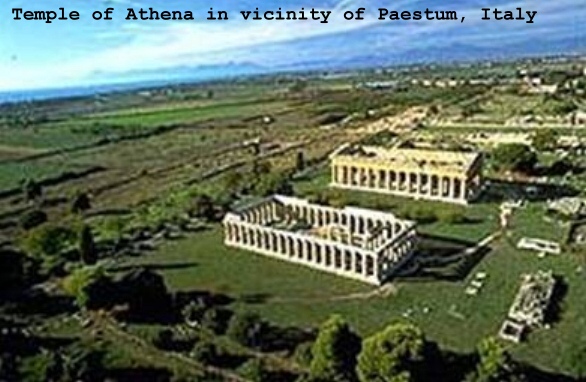

Ruins

of Paestum |

Sorrento,

beautiful town. No wonder they sing all these romantic songs about Sorrento. Small

sailboats bobbing in the water. And of course, all the Roman ruins and stuff like

that. Sorrento was a pretty little town. And of course, there were the Greek towns

like Paestum, the Italian town Battapaglia, this is what we became accustomed

to, moving into and around Naples. We, the 45th, did not attack directly into

Naples. We went around, and maybe the Third Division, I can't say for sure, captured

Naples. But I know the German's blew up the Post Office...boom! And they had alot

of Gallerias, you know, like we've got down in Providence. Great big Galleria,

and all the glass busted. So there was, with everything else, something to make

life worthwhile, sights to see, things to do if you got the chance. You weren't

fighting all the time. It seemed like you were fighting much more often than anybody

else. We'd seen our fair share, and always felt that way. The rivers, the names

I remember, the Sele River was down around Sorrento and in that general area.

Pompeii, you know, the wrecked town, Pompeii...talk about ancient, something that

blew up in the year 70 A.D. you know, after Christ, but not much.

Pompeii

today, I'm told, they've exposed much more artifacts than they had when I was

there. It was a small section, and as you might know, it was a small section that

was exposed with dead people covered in ashes which they covered over in plaster

or something. One section was the red light district and it could be embarrassing.

We were kind of naive, not like today. I can remember visiting Pompeii and there

was a couple of army nurses, and there was an Italian who was reading English

that he had memorized. He didn't know what the English meant, but some of the

stuff he said while he was reading and pointing out the mosaics mostly, the girls

would look away. Terrible. You didn't say the "F word" in front of women

when I was a kid. But it was Roman ruins, and they have since found hundreds of

bodies, hundreds. But there'd be, like a drinking fountain at the foot of a cobblestone

road and you could see where the stone had been worn away by peoples' hands getting

a drink. Interesting things like that. With the Roman writing all over the place,

the Latin, it was very interesting. Italy is a museum, no question. Pompeii, Sorrento,

beautiful place.

We left from just outside of Naples and Pozzuoli to land at Anzio. Pozzuoli, nobody lives there anymore because of the earthquakes a few years back. No one stays overnight in Pozzuoli. In fact, I saw a program on the TV, a guy's wife come in and makes him dinner, he stays, she leaves him his supper and then she goes, on the trolley car to leave there. Because, there's still the danger of aftershocks. That was Pozzuoli. And Old Smokey is still there.

We used transports at Anzio, LSTs (Landing Ship Tanks) LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry) and like that. The LST was a big ship, towered high in the air. It used to make regular runs between Naples and Anzio to bring up supplies and bring back seriously wounded guys. Wounded troops that required evacuation, couldn't be taken care of at the clearing hospitals that were on the beach. We took off from the general environs of Pozzuoli to land at Anzio. It was right outside of Naples. It looked like almost part of Naples. Naples was a great big harbor.

The landing at Anzio was uneventful, very little opposition. The Germans had left to resist what was going on down South, whatever operation it was, they sent what troops they had. They didn't need any troops there. And that was only a condition that lasted three or four days. So, we went in in reserve and filled in with the British First Army. That's the way we operated, and the 3rd Division operated on the other flank with Rangers. Rangers were in our area, too. They were a famous outfit. The Rangers were the ones at Anzio, when we first landed there, so now we're gonna do something, we're going to move out and expand the beach head. So they took 2 of our guns, 158th Field Artillery, we loaned 2 of our guns to the 1st and 2nd Ranger Battalion and they were going to attack out of their position in our area. And they got wiped out, Col. Darby and another, I forget what his name was. But they walked into this draw and they're all set, and up the other side and there's all the Jerries. It was hopeless. They all got racked up near Cisterna, near Viletri...they didn't get there, but that's where they were headed, Cisterna and Viletri. These are the same Rangers, reconstituted, that landed at Normandy to climb those cliffs at Point du Hoc. It was the same Rangers outfit, not the same personnel obviously. An impossible task to climb that thing and you know, knock out the guns that were there. And I guess they did a pretty good job. They silenced those guns for awhile because those guns would have fired on the whole beach either way.

We landed and moved rapidly inland 6 or 7 miles. We walked right straight up the main road heading toward Rome, actually heading towards the Pope's palace, Castle Gandolfo and so on, heading for the hills, heading for the high ground. We never got the high ground, we never got off the flats, and they were looking down our throats forever. This was an awful, awful place. And they kept landing more and more stuff there, more trucks, more tanks, more whatever we had. But there was no place to manuever tanks. They landed an Armored Division there, 1st Armored Division, 2nd Armored Division and there was no place for those tanks to go. They could go pretty good on the road, but boy, when you get bound on the road, they pick you off 1 at a time. Shoot the first three or four tanks in the front of the column and get the ones in the back of the column and you can leave the middle ones where they are. Because if they fanned out they would sink in the mud, in the canals and all that stuff. So it was a nasty operation, not much glory.

The only glory we had was that we did stop the Germans main drive. 2nd Battalion was largely responsible for stopping the drive. They came straight down the highway. We were lucky, we had shelter just off the highway, 500 yards off the highway. But poor old Cpt.. Sparks, his Company was straddling the highway. In the Battle of the Caves at Anzio, where General Sparks, then a Captain commanding E Company, 2nd Battalion, 157th Infantry took up position on either side of the main highway leading into Nettuno at the beach, and now G Company took up position on his left, outside of and into the Caves. When the attack by the Germans finally came to a halt, Cpt. Sparks and Sgt. Garcia were the only survivors of E Company, all the rest were killed or captured. Sgt. Garcia was later killed, leaving only Sparks surviving. He has even more reason to be haunted by this battle, I was inside the caves at least some of the time. We were under cover in the respect that we had men in holes on a little plateau outside the main cave. Our Battalion Headquarters was in the main cave. The cave had a roof that was probably 40 or 50 feet thick. They were salt mines at one time, so there were corridors and all that, just like Bataan.

It had to be better (going in as an experienced soldier rather than a new recruit). You knew everybody, you were a cogent, coherent unit. It's always bad, it's terrible. To live under a state of fear. And, you don't really know what you're afraid of. You're not afraid of getting killed, honest. Because, you figure, hey, big flash of lightning and that's it. But you're afraid that they might blow your leg off and you'll lay on the side of the hill for 24 hours slowly bleeding to death, hoping someone will come and pick you up. But that's the big fear, that you'd get badly wounded to cause death. My friend Staub. All I could tell in few words was, "Have you ever seen an automobile accident? Ever been nearby one or even in one? Did you have any warning? No. Well, so...and yet you could live through those seconds or moments. You can recall them with horrifying clarity. Little things that you would never have paid any attention to; pieces of newspaper flying around, a hubcap flying off into the air, that kind of thing."

I have a prime example of what first combat is like. This is at Anzio. We didn't get too much time, the invasion troops (we were reserve troops that went in a little later) so it was probably closer for us to the 30th of January, maybe. We moved up into position and someone had been there before us, relatively early days of Anzio. We had a radio operator by the name of T.J. Kanicki, and he loved to operate that radio. He didn't want to do anything else. "How do you hear me?" "I hear you fine." or "I hear you loud and clear." Anyway, Kenicki was quite a boy, he'd lost a brother in the war already. But he, personally had not seen any combat and he was a replacement with us. So, the first battle he saw, participated in and lived through, was the Battle of the Caves.

|

Battle

of the Caves Anzio, Italy Robert Benney, 1944 |

He thought we were all giants. He said, "These guys," (and he'd tell you, he'd have a couple of beers and he'd tell you, later) "Boy, you guys, Jeez, the artillery was landing on the roof, guys are getting shot all over the place and you guys just kept operating like this is what happens everyday." And it certainly wasn't. I had three battles in my lifetime, the same battles that Sparks had, that haunted him forever. And this was certainly one of them, but Kanicki thought we just took that in our stride. "Where do we get such men?" is what he was thinking. The whole tone of his first combat story was that, "Boy, oh boy, these guys, they've been at this already for almost a year." He just couldn't understand it, he thought we were just the greatest guys in the world. How could we be that brave? And boy, we weren't brave at all.

He was the radio man for Captain Sanders, the bald headed guy who was at our reunion. Sanders loved Kanicki, but Sanders, his memory is like a sieve. I can't believe it, he don't know nothing...it took him a while before he recognized who the hell I was. You know what it is, they say you block out memories that are painful to you. Our Colonel, Col. Brown the 2nd Battalion Commander was a most abrasive personality, never had a kind word for anybody. As a matter of fact, my friend from California wanted me to take over Historian and all that because I could remember all this stuff. I said no, and I asked him about how he got out of G Company into Battalion. He said, "The Col. stopped and talked to me one day." he says, "and I guess he took a shine to me." I said, "I never heard the Col. have a kind word for anybody." Honest, never heard him have a kind word for anybody. But, there you go. So Kanicki made out in that respect, and good for him. I like Kanicki. He's the guy that came from Akron, Ohio, he worked for the rubber company. He used to date Sally Firestone. You know, rich, alot of money. I remember, we used to correspond briefly, early after the war, Christmas cards. And he loved English, you know, phrases, He sent me a picture of his wife. Gee, she's a pretty kid. And I said, "a toothsome lass." He was pleased. He'd never heard the phrase about TV "the idiot's lantern". Oh, we got on fine. He didn't marry the Firestone girl, but he worked for Firestone for years and I guess, Tupperware. He sent your mother some stuff, you know mixing bowls and stuff like that. Just a hell of a kid. I wonder what ever happened to him. I would have loved to have seen him. Never saw him after the war at all other than to correspond.

We were talking, one time the conversation drifted to... this was during my combat days, before I was captured, this was at Anzio...this kid wanted to get into the conversation in the worst way. We were talking about rough and rowdy places in our hometowns or wherever, you know, the red light district of such and such a place. We were talking about mostly rumors as far as I was concerned, but, well. Some of the phrases that stuck out in my mind...this kid said, finally stopped all the conversation and said, "Let me tell you about this place in my town." OK, everybody stopped. We were on the recipe bit this time, we'd been eating K-rations forever. He said, "There's this great place in my hometown," Ohio or wherever, "My God, they serve the best potato pancakes you ever ate." How can I not cry...the poor kid, as innocent as...where do we find such men? We draft them is what we do. Jeez. When death be at your side, and that kid, that was what he remembered.

We were in the caves about a week, from the 17th to the 23rd. Anzio went on forever after the caves. From the 17th to the 23rd of February, the breakout was the 23rd of May. 3 months, with sniping, artillery, patrols and go get your prisoner and all that kind of goofy stuff. There was a time, in Anzio, when I was trying to get out of the Battle of the Caves, that we got fire with red tracers and we got fire with green tracers and they were intersecting at the corner of a house. We figured, the Americans are firing at us and we figured they could see us and they figured we must be Jerries. Honest mistake. Eventually, the last thing we did before we pulled out of there, we were supposed to get relieved by the British, and a couple of British Wellingtons, they were machine gun troops, they come in and they'd lost their guns on the road, the Germans hit them on the road, but they did get in. They were relieving us. Once they got into position, I'm showing them where what few troops I had, and they were gonna take over, and they lasted about a day and a half. And the Wellingtons were gone, and thus ended the Battle of the Caves, but the Germans abandoned the effort to try to drive us into the sea as Hitler said he was gonna do. They couldn't stand the losses either. So it was a stalemate, a bloody stalemate. Terrible thing.

The Battle of the Caves was the first big battle. And then, of course, this was the next battle, May 23 - August 4, 1944. May 23rd. Broke out of Anzio. I don't think I told you that, but it was just like the movies. Everybody just stood up and started walking toward the Germans. And the Germans fired, and pretty soon we had overrun self propelled artillery pieces. Never heard of attacking, and they abandoned the self propelled weapons. Until we were halted by a big terrain feature, a big canal 20-30 feet across. We had tanks, but tanks couldn't go across. How were we gonna get there? It would have just landed in the bottom, and there it would have stayed. Because, vertical sides, it was part of the drainage system that Mussolini's outfit had put in to drain the Pontine marshes. One of the great malaria capitals of the world. I got malaria there.

White Phosphorus was used to mark an area. It would flash and then a big cloud of sparks, great big sparks. Miserable stuff. It was deadly. Its nickname was Willie Peter (WP), and it was a high arc weapon. I can remember, in Anzio, when we had a listening post, and an outpost which was, say, 1,000 yards or so in front of our company rear at the time. The function of this outpost was to listen for Germans out there and call it in. If there was excessive movement, then the artillery would take over. There would be nothing you could do there from the outpost, and you didn't want to start a battle.

Anyway, we had this young man out there and we didn't hear from him. So I had to go out there, surely the line had blown out, the telephone line and patch it. I was extremely nervous getting out there. Anyway, I got there, and the soldier was sitting there with the phone in his ear. It didn't ring, this was not a ringing phone, you whistled into it, it was a sound powered telephone. I asked him, "didn't you hear us whistling?" because there was no break in the line. He said, "I'm deaf." So I said to the kid that was with him, "you take over." We were getting nervous because there was a lot of activity out there and we ran a heavier telephone line out there. We told him to ring back, we wouldn't ring him.

So sure enough, some time went by, a few minutes - half an hour, the telephone rings to headquarters and the kid says, "there's some guys out here moving around." The artillery observer was in our company headquarters and said, "Well, where are they?" He said, "Do you know where I am?" "Yes, I do" The artillery man says, "This is what I'm gonna do son, I'm gonna fire one round of smoke. You tell me where it is from where you are, 100 yards, 1,000 yards you tell me. So he fired one round of smoke and the kid gets on the phone, he says, "1,000 yards too far." So the artillery man, being very conscientious, didn't want to hurt anyone, said "I'm going to fire another round out in front of you by 200 yards of white phosphorus." He said into the phone, "One round on the way." You heard the thump, then a flash of light and the sparks flying everywhere. The kid gets on the phone and says, "My overcoat's on fire." He was alright, he stamped out the fire or whatever, and the Germans quieted down. But the forward observer said, "boy, we could sure use a guy like that in the artillery...what an eye!" But you didn't have much to go on. They told you that if you held up one finger, a foot away from your nose, the width of your finger at 1,000 yards was 50 yards. We used that method and in our day we had called fire down on our own heads. If you were sheltered, dug in deep enough, you could take a shot.

|

SCR

511 |

|

SCR

300 |

The Germans did not believe in shooting prisoners. I can remember when I Company, 3rd Battalion again, on Anzio, they were trying to hold off the German attack and were not doing so hot. The Battle of the Caves, we were losing, no question. Captain Grady Evans of I Company got on his radio, that's when we'd gotten new radios that were very powerful, and I'm listening to the radio like everybody else, and he said "The Germans (I forget whether he said Germans or Nazis or whatever) are pouring into the trench and heading towards the CP (which was where he was)" His next message was, "This is Grady Evans, roger out forever." What a dramatic guy. He was captured, they didn't kill him, they captured him. He had to be dramatic at the last minute. "Roger out forever." and he got captured. But the Germans captured him and this was right in the midst of battle, you know, so they captured several, and more, I Company people and they took the trouble, and it is trouble, to herd them through this. Shells are going off, everything's going off and they herded those guys through. They managed to protect them enough to get them going back to the German rear. That's the way they behaved most of the time. Certainly that's the way the SS troops we fought in my last battle, did the same thing.

During the breakout from Anzio in May, we had to move from one part or the battlefield to another. And the only way to do it, it seemed, was to go straight down this road. Cypress trees, very pretty. We started heading for that road and the Germans, of course, had it zeroed in, and they started blasting the hell out of it with artillery. So, we took cover at the side of the road, hunkered down to get away from the fire as best we could. You could see we had to get the hell out of there. Got to get out of there. So I called up the line, we were calling to one another and I said, "Where's Reyer?", Sgt. Reyer was the platoon guy who would nominally be in charge. (When he came home, Reyer worked with a funeral director and he'd say "I'll be the last one to let you down." Peele took over from Reyer, keeping G. Company together. Reyer was my first platoon sergeant when I had my squad.) They said, "Reyer got hit." I said, "Bad?" "Yeah, pretty bad." "OK" I said "where's someone else?" "He got hit, too." "Well, where's the squad leader?" He got hit, too, Sgt. Quail. OK, I stepped out into the middle of the road, that leaves it up to me.

I stepped out into the middle of the road and started down the road, waving my arms at these guys, and they got up and followed me down the road. We got down, not very far, 100 yards or more, and turned off the road and into a field. We were better off in the field. We started heading over to an American self-propelled gun. 105 mm gun which looked exactly like a tank, but it had the 105 and that was what it was doing was firing, so we went and huddled around that. Kind of stupid, looking back on it. The Jerries didn't know where it was. So here comes the German air force, a couple of fighters. They come swooping down at that gun, they could see it. They dropped a couple of bombs. I can remember, I had my head and shoulders dug in, dug in with a bayonet, that's about all I had, looking up as the planes went directly over my head. I remember thinking that in our aircraft identification and all that, if someone was to drop a bomb on you, when the plane was directly over head, that's when the bomb went off. And do you know, that's right. This bomb went off. Killed Sgt. Gray, not a mark on him. Concussion, boom, dead. Then I can remember, it was very muddy, so it blew up great chunks of mud that were falling on my legs. I thought I was dead. I thought, "My God, I'm dead." But no, it was the mud. Heavy casualties, and we had to get the hell out of there, too. So, we moved again.

|

LTC

Mark Clark's triumphal entry in Rome |

The Germans started to fall back and our orders were that once we got beyond the environs of Rome that we would be pinched out by the 36th Division who would continue northward, and we were now officially relieved, once we were pinched out. And sure enough, that happened and we got sent back on LSTs and like that, from the beach back to Naples, to train for Southern France. I arrived on the beach at Anzio on about the 27th of January. The first troops set foot there on the 22nd. June 4th-6th we were in Rome area, and Clark wanted to make sure that all the troops got a chance to see Rome, so that was probably another week (before being transported back to Naples.) We went back to Naples to train for the landing that were going to take place, as it turned out, on August 15th.

I wanted to mention Lt. Lemmon, again, for your history of mines. Lt. Lemmon, later on Anzio, decided that no one had been able to disarm an armed tellermine, without blowing it up. They used to take a rope or a flail and blow up. But he was going to be the first one, he saw it as a challenge. You know, like these bomb disposal guys. He goes out with his 536 radio, and he's talking about what he's doing. "I am now unscrewing such and such." He didn't go much longer than that. The tellermine went up, the whole thing, not the bouncing Betty, and that's all she wrote for Lt. Lemmon. That was at Anzio, pulling back to a so-called rest area. He was going to disarm a tellermine. No one had any luck disarming those bouncing Bettys. They were too light weight, you could hardly touch them and off they went. He was crazy. "I'm doing this, I'm disconnecting this....boom" I'm disconnecting me.

But you know, the anti-explosion people had to be something special. You have 2,000 lb. bomb in England, and a guy's working on the front end of it, which should have gone off. He's taking that end off to try and disarm it. Nerves of steel, boy. You see alot of thriller movies....don't touch that dial. |

Br.

Matilda Scorpian Mark I |

Well, they were terrible things, but we used mines too.The best thing to do was find them. The British came out with it in the first place. They had 2 long poles coming out from the side of a tank, on the front of the tank, with a big drum mounted across, loaded with chains. They would start that chain up, flinging these chains and they would drive over. This would blow out the mines 10 feet or more from the front of the tank. They would clear a path that way, which was pretty clever. That was a fairly wide path. Then, of course, we adopted that, too. We had tanks with flails on it.

Mail would get to us, mostly V-mail. You'd get mail, and it would be sent up, or the mail orderly would bring it up. Depending on how close the rear headquarters was, some cases it was only a hundred yards, mail would come up from Battalion in a Jeep, they'd drop it off, and you'd sort it out by platoons, I used to do that, too, on the side of the mountain. Everybody wanted their mail. Tubby Bryant, God rest him, was badly wounded on Hill 770 around Venafro. The litter bearers were bringing him down the mountain to rear headquarters, where I was with all the mail and packages, and we were buddies. "Hey Wims, I got a fruitcake there somewhere." "OK" He said, "Well, put it on my litter." I put it on the litter with all this mail. I can still see him, face all blackened with mud, blood. I didn't know how badly he was wounded. He did survive, I talked with him later at my first reunion. He survived. I could see his big white teeth shining.

|

Hill

769 (770) |

That's when I lost my job. I was the mail orderly because the mail orderly was sick and I was a Corporal so they made me mail orderly for the time being. I figured, "Boy, have I got it made." I didn't care about rank. I looked up after talking with Tubby, and here, up the trail comes my friend Bob Leek, from Philadelphia, the mail orderly. I said, "OK buddy." So that's when I got promoted to Sergeant. I got promoted and took over a squad. Thanks a bunch! The 770 attack was a fiasco, we had to use smoke to get our men back off Hill 770 (around Venafro). The 770 referred to the height of the hill, 770 meters, @ 2,000 feet high. You wouldn't climb it very easy. And the next night, after Tubby left G Company went back up the hill to attack 770 again, so I got to participate in the the second attack on 770. I had a squad now.

After Anzio we were in the fields near Rome and visiting Rome. Then we were ordered to report to the beach for boarding LCIs, LSTs and going back to Pozzuoli outside of Naples. We did training there which was mostly looking at beach obstacles and how to blow them up. We got introduced to the so-called "Beehive Charge" which was a rather large canister that some soldier was supposed to sneak up on top of some German pillbox, and if it wasn't a pillbox it was just a great big cube of concrete, still, get out there and arm it and blow it up. The charge would turn the cube of concrete into rubble, and it really did. And of course, this was designed for two purposes, one to blow up beach obstacles, and another one, to dash off onto a nearby pillbox occupied by Germans who were all the while firing at you with machine guns, or artillery pieces perhaps from outside, and blowing that up. We always felt the big question in our minds, who was gonna bell the cat? Who was gonna bring this deadly charge, set it up and arm it? I guess they figured somebody was gonna do it, I don't remember any incidents at Southern France when we got there of doing so.

|

St

Peter's Bascilica, Rome |

Re: Seeing Rome. I saw all the sights, all the sights. St. Peter's Square, the Chapel, the Basilica, climbed to the top of the dome, circles, circles right to the top, looking straight down on the altar. The marvelous twisted columns. And my pronouncing first impression of Rome was the statuary. It could be a statue of St. Patrick, say, and you knew it was St. Patrick, you'd seen pictures in your Bible and stuff like that. And it would say in Latin "Patricus" or whatever. But it looked to me, that if someone opened a door right next to the statue, the marble would wave in the breeze (gesturing to indicate the hem of a robe). That's how marvelously well done it was. And Pieta, the most beautiful woman in the world, right there, there she was. The most beautiful 16 year old girl in the world, Mary.

The Coliseum, of course, a den of theives, even then, when we were there. Looking up at the Sistine Chapel ceiling, God! Across the entire dome. Again, it seemed that if the wind blew, that little fog would blow away and you'd be able to catch a glimpse, a better glimpse. Oh, I was so impressed and so knocked out with that, I couldn't believe....and when I went back to Rome with your mother, I didn't get that magic feeling quite as much, but I pointed out to her how it felt to me. And the awesome figures of the various Popes, coming out of his tomb. God, it would stop your clock, with his hand outstretched to join God. Probably in Rome a week, ten days, back and forth. Went back to Camp every night. Camp, fields outside of Rome. It was 10 miles or better. It was a good Jeep drive. One of my dear friends was a supply sergeant at the time, and made sure that I always had, if any samples came in of a new kind of winter combat gear, I got a sample, like 100 percent wool and it felt like silk, light, it was a new waterproof. I put on those longhandles and it was just marvelous, marvelous.

It was a usual beach landing, try and take the high ground, that sort of thing, which in our fortunate case at the landings in Southern France on August 15, was accomplished when we went in alongside the 36th, and 3rd American Divisions and 1st and 2nd Rangers, 17th and 18th Airborne (gliders and paratroopers to the beaches near St. Tropez, Cannes and Nice). We did not encounter any serious resistance. Yes, there was gunfire and so on, but we moved across the very short beach and there was a brick, concrete road running the length of the beach and the engineers had blown a hole in it. Of course there was only one hole in it so everyone was filing down to the right or left as the case may be, and pushing their way through this hole and fanning out on the other side and up into the hills that were right there. We accomplished this without much problem.

The battle moved rapidly inland. It was the largest invasion, other than D-Day, June 6th in Normandy France, at the time. In no time, we were at the town of Le Luc. It was, by now, a nice sunny afternoon, around noontime. I asked a very pretty French girl, looked like Simone Signoret, were there any Germans? She said, just down the road "Beaucoup Allemands." Meanwhile, |

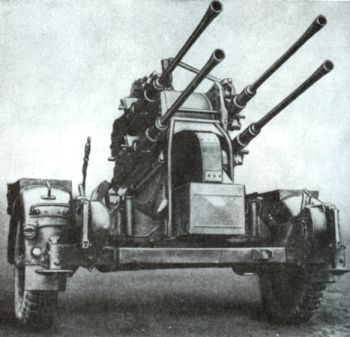

2cm

Flakvierling 38 (20mm Quad AA Gun) |

This was the Task Force Baker Campaign, based on the Rhone. We fought our way through Montelimar, we fought our way through Lyon as part of Task Force Baker, General Baker's special task force, where we took off to the left, to seal off the retreating German 14th Army. And we did seal them off when we showed up by that flak wagon, that was part of it, part of the resistance.

As we were going through...it can be Bourg just as well, I guess...up aways past Grenoble. We had started to run at the Rhone through Lyon. It was in Bourg that this guy was walking down the street and he yelled out "Is there anyone here from Pawtucket, RI?" I raised my hand and said, "I am...whereabouts?" He said, "Do you know where McCabe Ave. is?" I said, "Yes, I do." So we passed the time of day...right in my Darlington neighborhood, in the Broadway neighborhood....you know the State Line Diner, that's where McCabe Ave. is. This was a civilian living in France (who asked) That was probably in Besancon on the way to Epinal.

We made Epinal, we went through Epinal....Germans on retreat. Then we got up towards Mancip, Metz, and that's where resistance stiffened. We were getting pretty close to home base for the Germans. The direction of our attack began turning towards Munich.

As far as I'm concerned, the battle stopped for me at Riepertswiller (Battle at Reipertswiller January 11-20, 1945). We made a turn at Aschaffenburg(Battle of Aschaffenburg March, 29th - April 6th, 1945 ). It's fair to say I did not participate, that was the only battle that the 45th was engaged in, noteworthy battle at Aschaffenburg. But the 45th did indeed fight at Aschaffenburg. Terrible battle. Last significant battle of the war for the southern armies. So I was in prison camp, I was in Riepertswiller during Aschaffenburg. Metz and Sauerbrucken and Kaiserwaltern and I wasn't in those towns but I was in rough country there. So this was January, New Year's day or shortly thereafter. New Year's Day, 2nd, 3rd we were maneuvering before Aschaffenburg, heading in the general direction of Munich. We were too far away to worry about it. And in the direct direction of Dachau. Dachau was quite a ways from Aschaffenburg, right? So the attack had continued north.

Riepertswiller was essentially where Task Force Baker ended and became the Vosges Campaign...was the Vosges Campaign. That's where we headed north at the pass. Burning tanks. Stopped tanks. Guy sitting in front of a tank, German guy. Guy behind a tree with apple blossoms covering his shoulders, covering his staring eyes. Nothing to blow them away, landed in the guys face. I've always been trying to place this...it so impressed me. It's a memory that stays with me. I can't get myself located geographically. So, it had to be at the end of the campaign in the Vosges.

I ended up by going in and out of Neiderbronn which became like a home base for us and we'd go out to these surrounding little towns like Bult, Ramberville and Bru . They're too small to appear on the maps but they're in the area of Aschaffenburg[ Over 100 miles away]. So we stayed at campaign....and me, I'm already in the bag before Aschaffenburg and after Bru and Ramberville and Bult. Three towns the 45th was engaged in. We'd run in and out as we lost people and close off the line, close up with fresh people. My job was to go out ahead on a quartering party through the towns like Ramberville and I went out and knocked on doors and say "we'd like to stay". Most of the time they'd say "you can stay down cellar" and OK, that's fine. We never made anyone move. That's where we stayed and worked in and out.

We had parkas, when we were fighting around Riepertswiller, the Germans had parkas the same color, green on one side, green with camouflage mostly. We had green on one side, with white. So the Germans had the green side out, so we put the white side out. Then the Germans did the same thing, and it was awful. They'd be coming down with a sled, a machine gun mounted on a sled, pushing it through the snow, sliding down. We could hear them, but at 200 yards you could not see them. You could see the bushes move, so you'd start shooting at the bushes, aim low, you might hit something. You don't hit 'em, you throw dirt in their eyes. So it was an awful battle, awful battle. And when I found out after the war.... when I asked Sparks, I said, "General, you and I have been haunted by the same three battles, what happened after they drove us off the hill and we surrendered?" He said, "They abandoned the field, and we did too." What a waste! It was all for nothing, they abandoned it. And those two poor souls fifty years later, they were dug up and took home to their homes near Boston, their remains. God, it's terrible, terrible.

The battle went from the 10th, we were back and forth, milling around. Started on the 10th and then around the 18th they closed in on us, and from the 18th to the 25th it was strictly the battle of Riepertswiller. On the 25th it was all over. We were surrendered and marched off the hill. I had a German lieutenant tell me to put my hands down. Put your hands down, put your helmet back on. He said, "We could both get killed." And we knew, I knew that our artillery was coming in. He knew his artillery was coming, both at the same time, 5:00. We were sneaky, we tried to, we launched another attack from 5:00 to 5:30 and were beaten back, we got nowhere. Nowhere at all, it was worse than before. There were more in front of us, and we got through pretty well to go help out the third battalion. But there were more in front of us than there ever were in back of us. But they kept coming around over time.

When they knocked out our mortars, our 81 mm mortars, which we controlled, and then the 4.2 mortars which guys like my kid brother Mickey controlled, they were further back, right in the town of Riepertswiller. We were never in the town of Riepertswiller. Only going through to maneuver with the 103rd Division and the 100th, 102nd, all the divisions we maneuvered with. And they'd get knocked off the hill, and we'd be ordered to go back up and get the land back. They were rookies, they didn't panic. Everybody panicked, we panicked. Awful thing to see, panic. Awful thing. I can see the wild look in Sgt. Farmer's eyes. He came from NY, and he was a farmer. Just go ta house, was his favorite expression, you know, we're through for the day. But "What's the matter Claude?" And he stopped only long enough to say "There are jerries all over the top of that hill." That was like 500-600 feet away. So I said OK, let's...so we all haul...all of us, no question get to the bottom of the hill and say what the hell are we doing? What are we doing? This is no kind of order so we reformed and went back up again and started the battle of Riepertswiller, to its gory finish.

Again, in my last battle, we had a battalion of 4.2 mortars from the chemical battalion were firing in every 30 seconds or so, a round of 4.2 with white phosphorus to cover our wide open flank so the Germans could not come in around us. But, shortly, during the week or so that we were active fighting the Germans at Riepertswiller, they knocked out the chemical mortar. So we had no more supporting fire there, and the Germans were more free to move in around us. This, again, contributed to the disaster.

The whole thing started because of the Battle of the Bulge, indirectly. Eisenhower ordered all the troops that were or were not available, even if they take them right off the line, take 'em right off the line. These are the best that the jerries have. He finally realized that. So Patton rounded them up. And he said he could make it in two days. He said in 2 days he'd be at the relief of Bastogne. And he was. He got there with the 82nd Airborne, which was down with us, and he got there with the 101st Airborne, which was down with us. And he got there with the 118th Airborne, 117th Airborne. He got there. And he broke that ring, no doubt about it. And Eisenhower wanted to reform his lines now and pull back. And he says, "Ike, I will ask to be relieved before I will do that. And you can explain to the American people why you sent me home. Because I will not, repeat not, call off my troops. They're there, they've done the job and they will fall back in good order when the time comes. If that is necessary, I'll do that, but I will not do it now." And Eisenhower leaned on DeGaulle, "abandon Strasbourg." And DeGaulle said, "Not on your life. We're here, and here we shall stay. And you can explain to the world (a global figure, DeGaulle) why you ordered me to abandon Strasbourg. And I'll explain to them, if I survive, why I didn't."

I think that's as far as I can take you there. Cause I didn't fight anymore. I fought, on the side of the mountains for a significant time, November til January 3, 4, 5 then maneuvering around Riepertswiller, bringing in new divisions and new divisions would take over from us. We'd pull back out to Bains le bains or Martigny le bains or Neiderbronns or one of those. And sure enough the Germans would knock these guys off the hill. So we'd come back and find the new guys which we'd send back. And we did our share of bitching but if you caught the wrong side of the hill, too bad. One time I caught the wrong side, one time I caught the right side. The right side is where I got knocked around, again, Riepertswiller, you know.

So that's the way it was, in those days as our numbers dwindle, dwindle down to two, me and Sgt. Bierman from Stateside. I have to distinguish because I wasn't in some of the places that he was, in the states. But the top non-coms were Bierman, Wims, Elliott (Elliott had gone home) and Jimmy Bridges from West Virginia. Jimmy Bridges was a top non-com if there was gonna be a new first sergeant it was gonna be Bierman, was gonna be me or was gonna be Jimmy Bridges, no question. And it worked out because I guess Nichols like me more than he liked the other two guys, simple as that. Put it in! Old Nichols was the commander of the day or maybe two, but he wanted to exert his authority. The hell with that noise, I'm the boss. The end of that. "Brown will not sign it." "I don't care, somebody'll sign it." But nobody did, and I tore it (my promotion) up as the Germans came down the hill.

Johnny J. Malish, last time I talked with him was a Staff Sgt., 4 stripes. We were on the side of the hills, fairly close to Riepertswiller. We didn't know what was coming at the time. In the United States Army, in Paris, they were having a hard time with soldiers on furlough. They were all going AWOL, but even soldiers that were going AWOL tended to have respect for guys that wore the combat badge. So, the Army, in their wisdom thought it would be a great idea to maybe get some MP's back here, who were combat-wise and wouldn't take alot of that stuff and could read ribbons and so on. So, I walked up to Johnny, we were never friends. I said, "Johnny, how would you like to get busted to Sgt.?" "What the hell for?" I said, "So you can go back to Paris and be an MP." "You're kidding!" "Naw, that's it Johnny, we need a guy," I says "You're regular army and I think you would be ideal." He said, "When do I leave?" I said, "In five minutes." And off he went. And I am sure that wherever Johnny Malish is today, he'll say, "Oh, I had a friend once." I said, "The only reason I'm sending you is I can't send myself." Johnny was the kind of guy who would go into town and get busted, professional soldier. He'd go into town and get busted and maybe drink a little too much and maybe wind up a private again. And he'd have to start all over again. He'd start all over again because he was regular army. He had alot of years in. A good man, Johnny was a good man.

The other regular army man we had was Captain Walker, who joined us for the invasion of Southern France. He was leading the company up the hill and he stopped us, everyone stopped at the so-called "military crest", short of the crest. "No, no," he said, "I don't want my men resting, at the crest.' And resistance here was relatively light at the time, he said, "We'll go all the way to the top and rest there." So that was one idea of his thinking. Later on, we had one of our tanks that was supposed to come along with us and help out. And the tank was a little bashful about coming forward with the front line troops. So Cpt.Walker banged on the side of the tank with his Tommy gun, the guy, you know, opened up the turret, looked out the hatch and said, "What's the matter?" He said, "I want you to move this thing up" however many yards. The guy said, "We're alright back here." He leveled his 45 sub-machine gun and riddled the side of the tank. The tank moved up. That was Cpt. Walker. I don't know what happened to Captain Walker. As far as I know he didn't get hit in that particular segment. I remember that about him, he was a West Pointer. One a West Pointer and two, Johnny Malish, a regular army soldier, dogface. Walker was a West Pointer, as he would say "a lieut from the Point." Good man. As my friend Colonel Foster would say, "Good school. You'll learn in four years of "see that your men have dry socks", I learned that in six months." But it was true, they learned to take care of their men, and look after their chances for promotion."

After my capture by the Germans at Riepertswiller, when Capt. Curtis formally surrendered the 3rd Battalion 157th Infantry on January 25th, 1944, it took about four days to walk to Stalag 12A with a one day stop at Landstuke, a day's march away from Stalag 12A at Limburg, Germany near Frankfort. Upon entering the prison compound we were met at the door by a British Red Devil (because of the red beret) paratrooper, no doubt captured after the joint venture by the 82nd Airborne and British 1st Paratroop Division's failure at Nymegan Bridge. "What's the matter with you Yanks, can't you fight?" My reply was, "What did you do, shoot your way in here?" That turned out not to suit his sense of humor.

On the walk from Landstuke, Germany a transit camp to Stalag 12A at Limburg, Germany, we stopped at a German Cavalry Barn. The horse stalls were ceramic tile cubicles (incidentally, the same color tile as we have in our kitchen) with hay and straw on the floor, thoroughly soaked with horse urine. Temperature was way below freezing and we spent the night laying down and trying to sleep. I learned the meaning of the phrase "bone chilling cold".

We were heading out of Riepertswiller to Camp Marlag-Milag....we're going out, going further north, and the politicals are coming in, I don't know where they were coming from, and their in bad shape. And there's one where the guy confirmed my story, I flipped my cigarette across the street, and this prisoner, Russian, Slav, whatever, reached for it. And the German guard, with his riding crop, just swung it....swung his whip at him and hit him on the arm. The guy died. That's how close to death he was.

Master Sergeant Jack McGee, 1st Rangers Battalion, was in charge of Marlag IIB. We had just completed a four day boxcar transfer from Stalag 12 A at Limburg to II. We spent most of the four days backed into a tunnel with nothing to breathe but Carbon Dioxide, Carbon Monoxide and Sulphur Dioxide. Men died on the train and for days after in 10 B Marlag. During this time, Mst. Sgt. McGee would address the troops after morning roll call.

M/Sgt. McGee would say, "Yesterday, in the Lazaret, 3 comrades, name, name and name died yesterday in the service of their country, starved to death." A guard who understood English joined us at attention and saluted. He later came over and bawled out M/Sgt. McGee....the Wehrmacht did not starve prisoners. Next day, McGee addressed us after roll call again, "Yesterday, 3 more comrades, name, name and name died in the service of their country, malnutrition." The German commander joined us at salute.

By and large, certainly in my case, no matter how starved I was in prison camp, I felt that I was always treated with respect, mostly. Some of us infantry combat men...the air force didn't like the way we treated the Germans and the Germans treated us. They figured you had to do everything possible to bring the camp down. And I believe that too, I had no problem with that. I used to envy the air force. Then I thought, gee, that isn't so good to get out of a warm bed and go fight all day in the air, lose your buddies and so on, and then come back home. Maybe it was better to be constantly under it than in and out.

But, I had a dear redheaded friend, and we shared the running of our little compound. We got to be great friends, and I didn't have any air force friends. We used to kid back and forth. He hated the Germans with a passion. I understand it now. I didn't understand it then. It really hurt me, we separated. He took half a group, and I took half a group. We ran the compound together and we liked each other and it was just great. You know, you don't have too many friends and you hate to lose one. But I could understand him years later, I couldn't at the time. But now I can. We had our share of bloodthirsty guys too. But he wasn't bloodthirsty, it was a defense mechanism. The Germans to me, it was a personal thing. We looked into each other's eyes, you know. I couldn't see the difference between a young German of 22-23 or me. Physical characteristics, Germans are pretty much Northern Europeans, like Irishmen are, look at your descent. I realized that they had to hate them because, most Americans are not violent people. They don't kill people. There are always war glory hunters, there are always those. But by and large, the vast majority of American soldiers were not violent, even though we were engaged in combat, they were still not violent. It wasn't their natural instinct, to shoot somebody or kill somebody. You had to get yourself up to it or do it en masse with your buddies.

I wouldn't want to know that I killed so and so. I wouldn't want to know that. Uncle Larry couldn't understand that. He'd said, "Did you ever kill anybody, Cody?" I said, "Larry, I sincerely hope not." But I don't know, I don't know. But anyway, I felt that he had to, he was daylight raids, American Air Force daylight raids. He could see the bombs going down. He could see them burst and he knew this was a populated area. You know, it doesn't just pick out all the 88 mm guns, and leave the civilians alone. So in his black heart he knew that they were killing, that what he was doing was killing people just like himself. So he never thought of them as people. He thought of them as Nazi bastards, and you know, they're going to take over the world and we gotta knock them out. It's a noble mission. He had to do that. It's understandable. You have to assume this, and so you start calling them names. They're not humans anymore, they're Japs or they're whatever. And the Japs were worse, I could see it. I would be more frightened of hating the Japs because I would think you would almost have to. The Geneva Convention didn't mean a thing to the Japanese, mostly it did to the Germans, mostly.

The Germans who captured me at Riepertswiller, how well they kept their promise. They said to Curtis if we surrendered under a white flag, they would give us the best treatment possible on the way back. I thought that meant to the first Stalag we hit, because the Stalags were not run at the time, or at any time, by the SS. The SS were a very important force. Evidently the Waffen SS, the fighting men SS, took higher casualties than the Wehrmacht through the entire war. They said that they would see that we were well treated within what they had. It was a great surprise to me to see that that went beyond the first, second and third camps, or stalags, I was in. They never roughed me up, and to my certain knowledge, never roughed up any 157th Division prisoner, unless they really acted up, flagrantly, they might stand him on the wire. They'd make you stand out there in the cold for an hour, maybe more. Or they'd toss you in the cooler, even worse, you're outside in a little dog house, they'd throw you in there, no light, no nothing, for a day. You know, like the movie actor Steve McQueen. I never saw anyone stood up on the wire. So they must have had orders. In that respect, that came as a complete surprise to me, how well the 157th troops that were captured with me, non-coms that were captured with me, I can't speak for the private soldiers, they were by and large in different camps, but the non-commissioned officers from Corporal up, were never maltreated. We didn't get enough to eat, but nobody else was getting anything to eat either. Simple justice, you couldn't say, they didn't have it, how could they give it to you.

I remember the admonition, when we went out on carrying parties. They needed the non-coms to work, they had to ask your permission almost, to work. Being sent out on a working party from the camp at Stalag 12 at Limburg, near Frankfurt. We were going to pick up American and British Red Cross parcels, and there were 5 men in each box. They said anyone opening a parcel between here and the return trip, will be shot. So there was ample warning. Somebody might have been rifling those packages, but if there was, it wasn't the Germans. And I believed that. There were alot of complaints, but I would sign no complaints because I saw no evidence before me. I heard vernacular evidence, or people complaining, that they were rifling packages to their advantage, non-coms in charge, American non-coms and British non-coms. But I would not be a party to signing that because I had no knowledge of it other than gossip from American prisoners, including 157th guys, gossiped about it, and they wanted to assign charges against a couple of non-coms after the war. Long after the war, twenty years after the war I'd get letters from private soldiers, now civilians after the war saying Sergeant so-and-so , I won't name him, why should I, he was getting into, I know he was rigling those packages.

I had guys in my own company who would say, "You're saving the best parts of the soup for yourself." And I would say, to a man twice my size, 6'5" with a scraggly beard, "Here, take mine now." And he wouldn't do that. "Take mine and give me yours." I was relying on two guys that were cooks in some outfit, not the 157th. They wanted to help out. They'd say, "I was a cook, I can look at a bucket like that and say how many saucers do you want? 50? OK." And bing, bing, bing, there'd be nothing left. With a smile, I repeat, I know of no incident of Americans or British robbing . I've seen there were older prisoners, who had been in prison three years, five years in some cases. Those that had been there five years had struck an equilibrium with their diet and the demands of the diet with the food that was set before them, within that limited diet. The Germans were clever, they designed a diet you would not starve to death. It would not kill you, it would sustain life, barely, at a very low flicker. But abusive treatment, I know of none.

If it was a nice warm day, you could go outside and exercise. You could walk around in endless circles around the camp, yelling at the Russians, whatever. The Russians were on the other side of the wire, the wire I was telling you they stood you up on. A row of wire here and a row of wire here, running all around the camp. And then, inside the wire, there was about five feet from the single wires was another wire about 4-5 foot high. If you touched that, you'd get shot. And they'd shoot you. It was the same thing on our side. We were very careful to stand 2 feet away from this second wire. And we'd harangue the Russians, they'd have some tobacco in a brown paper bag and you'd say "how much". We had cigarettes. We had American cigarettes, we had British cigarettes, we had German cigarettes, part of the ration. And the Russian would say "ten". OK, both arms go back at the same time, and throw the stuff over the wire. And they'd scramble for it on the other side. And I'd scramble, put it in a Prince Albert tobacco can. God, we used to roll cigarettes out of that. Some of the guys had a machine so you'd wait to have it rolled their way. One drag and, you're looking at a confirmed smoker, I'd been smoking for years and years, it would stop your clock! Oh God, it was awful! But you still took a drag...got to have that cigarette. Some of the Russians spoke broken English, and I knew some Russian from growing up with Polish people...you know, Russian/Slavic, it's close.

They got you up at six o'clock in the morning, every morning. They had to count you. Germans had a passion for counting. They figured if the counted you often enough, no one would ever get away, no one would escape. They didn't want anybody to escape, and as far as I was concerned, I was in no hurry to run, not over 50 miles...I'm still in Germany after all. This is their hometown, they know everything, I know nothing. If it was a lousy day, you'd go back inside, sit with your back against a pole if you could find one, or the wall, and tell war stories or exchange recipes. How your mother made donuts or how your mother made soup, or how you yourself, some guys had a flair for cooking...we had this sergeant that was captured, your tongue would be hanging out of your mouth, dripping like a dog, talking about how raised donuts were made. "You popped them out of boiling grease," he said "And you tossed them into granulated sugar or powdered sugar, you couldn't wait for them to cool." These were recipes, nobody had any donuts, nobody had any flour, nobody had anything, but it was something to talk about. You'd get some of the other guys and everybody had a story. As Jimmy Durante said, "Everybody wants to get into the act."

Guys stood on the wire from different outfits. And that's not even fair to say that, I'm not even sure of that. The 28th Division from Pennsylvania fought in the Battle of the Bulge, and there were 28th guys telling me about the battle in the hedgerows and we were talking about that, and I had no experience in fighting in hedgerows. They told us how awful it was. I talked to guys about it, guys from the 28th, the bloody bucket Pennsylvania Division. And he said, "Louie, it was so awful. You couldn't move. You'd leap out of one hedgerow and get 20 yards or 30 yards in mortal peril to get across that next hedgerow." And the Germans would eventually...hand to hand combat, shooting each other point blank, he said, you know, right in the face and they would abandon that row and fall back. Slowly, determined resistance. Awful, awful, and I'm proud not to have participated.

And you know, we talked about Anzio, they said how was Anzio. And I said, you know, every battle....one battle, whether it lasts a week, 10 days or whatever it lasts, is Godawful. But then there's the time in between and preparing for that battle, and moving into that battle and everybody's walking and it's just like, honest to God it's just like the movies. When they decided to now try to break out of Anzio, and they did seize Rome. As far as they eye could see were American, British, whatever we had, everybody, whatever we had in Italy at the time, combat landing, walking slowly, fanning out over 7 or 10 miles deep by seven miles wide, or 7 miles deep by 10 miles wide. And the troops started to (unintelligible) small places. Everybody looked, hundreds of troops, marching over, walking slowly over and through tanks, foreign tanks, not our tanks, our tanks trying to be with us, staying far back if they could unless they ran into a Capt. Walker or something like that. But that's the way it was, and those who participated in that battle....a common expression, "just like in the movies". It looked like a John Wayne movie. It looked exactly like that. So Hollywood, in many ways, knew what they were doing.

So, I never saw any 28th prisoners stood up on the rail. I knew that in 12 A there were British prisoners who'd been loose in Germany for a year already, this was in 1944, and they captured them. They said, "Gee, we only had another couple of hundred yards and we would have had it made." And he was wearing British Battle dress, instead of his kilts, he was from a Highland Regiment, he had those skinny legged pants - trues. Black Watch color. I said, "Geez, I don't know how you got away with wearing that." He was funny. I said, "Are you gonna try again?" "Ah, what's the use, Yank? It can't be much longer." That's the kind of thing you'd talk about. I was vitally interested in talking to him. I said, "So what happened when they picked you up?" "They threw me in the cooler." But he was out joining the general prison population. Where do we get such men? A whole year wandering through Germany, a whole year. Maybe they caught him in Africa. They didn't catch him in Russia. Maybe they caught him in Italy, I didn't delve into that.

Only this Limey and a couple of others with him escaped and they hauled him back to the cooler. No one made a successful getaway while I was there. Tunnels, they were digging tunnels all over. Where do you get the wood to shore up your tunnel? You get it from the sub-flooring of the barracks, you'd hang down at nighttime, no light, and tear off planks this long or however long would fit, and a man could crawl. You'd take tin cans to scatter the dirt over yards and yards and pretty soon it would assume the same muddy color as everything else. But they were always digging tunnels, and if you looked, like "The Great Escape" at the panorama of where they were in various barracks, and look at all the broad open expanse of several hundred yards to the woods. Once you got out, and got into the beginning of the trees, where if you came up near enough to the trees and turned, you could run like hell between the beams of the searchlights. But there were no great mass escapes. "The Great Escape" was the greatest one, and that was very likely true.

The Russians didn't escape, if they went home they would very likely get shot, and they knew that. The Germans would only shoot them if they were running. If they were running towards the Russians and got shot, what justice is there in that? So there was a sea change of feeling for some of us that were in prison. I never bragged about it at all. They asked me on my termination interview from the service, "Well, if you're not going to re-up, here's your service record here, you've got all your medals and how you won them. Do you want me to put down about your Prisoner of War?" I said, "Well, I'm not particularly proud of it. I'm not particularly ashamed of it. Whatever you think." So I think he did put it down, because it tied in with my medals. The most insulting thing of all, was that they came out later with the POW medal, and I sent in my papers with the POW's and boy, when I got that medal, was I insulted. There was the box and in the box was the citation "at your request Sgt. Wims, here is your exPOW medal" I didn't ask for it, it wasn't my request for a medal. If I have a medal coming, I want it. It didn't do me any good. That's the War Department, they are so neutral.

Even though I starved to death, that was more my fault I guess. I wasn't used to surviving on miniscule rations and in 3-4 months time I lost 60 pounds. So I certainly wasn't very rugged at the end of my...it's strange that how my condition then (and now) are going to be parallel.

I was acquainted with with Dave Powers (later aide to President Kennedy) in prison camp. He was a politician, he was a likeable guy, I don't take that away from him at all. But he had a mission in life. And there were alot of guys that had a mission in life. There was an American by the name of Jack Hawkins. And Jack Hawkins was a professional ball player, next step major leagues. And he was moving up to the major leagues, he got drafted. Biggest disappointment in his life. He said, "so I put on, like the rest of us, two years of combat, a whole army hitch." Changed him completely. He said, " I'm not as fast as I was, I can't throw as well as I could." He says, "I know I won't make it now when I go back." That was a great tragedy. I served with him in the prison camp. I met him and talked with him and I, quite a few guys I spent time talking with. You had alot of dead time, you can imagine. They counted you at 6:00 in the morning and they counted you again at 4:00 in the afternoon, just before it got dark, or whatever time you needed to get counted, twice a day, roll call. They had a passion for counting. But it worked. I mean, I already told you the most amazing thing is that they singled out 157 guys for, not special treatment, but, if we obeyed the rules, we would not get picked on. Others got picked on, we didn't. And I couldn't believe it.

|

The British told us to come in on a bren gun carrier which is like a small track vehicle, 2 tracks, full track. And they would turn by stopping one track, and keeping the other one running. They could turn on a dime. They came in, a couple of them, loaded with bread, that's all they had, bread and some jam, and they were throwing it out. "Now Yanks, don't go mucking about the battlefield, because you'll only get yourself killed." And the Germans abandoned our camp, and ran into the woods nearby. The whole camp was surrounded by woods, and it was only the first night that the British had come in. The second day, they came in with a flag of truce and wanted to surrender. And wanted us to send someone out to bring them in. I said, "No, we won't do that. I told the outpost guard to go back and tell them that they were welcome to come in, and they would be our prisoners, but they had to come in." And quite a few of them came in. So now, we're guarding our own Camp, and I'm issuing orders to these guys, and some of the British ignored me. We had British and we had Air Force guys, not people that uniformly hated one another but the respect wasn't there at the time, and I see this guy go and he says "Yank, I'm sorry, but I want you to know, I'm going into town, into Severn, and see if I can hunt up some women, or if I can't hunt up some women I'll hunt up something to drink. I'll be back, don't worry, Yank, I'll be back, I won't disturb you in that respect." And off he went. I wasn't gonna send guys out with rifles to bring him back. Go ahead, and you know we were free, we were all free.

|

Then they flew me out of Milag und Marlag on a C-47, maybe that one that you flew, a British C-47, and set me down at Brussels. And we stayed overnight in Brussels and then the following morning we headed for LeHavre to Camp Lucky Strike. And I went home, the war's going on madly, shipped home the 29th of April I was out, so say, 1st of June, 2nd of June it was almost 4 years to the day when we hit Boston harbor. In Camp Lucky Strike, April, including a 4 day trip across the ocean, about a month. I missed a couple of shipments because I come down with blood poisoning from my arm and they locked me up in Le Havre in the hospital. Got the blood poisoning from a louse bite or tick bite or some kind of bite that got infected.

Trying to keep the lice away, and I'd done a pretty good job, most of my guys had done a pretty good job, raised hell with them all the time. I saw this new guy who'd just come in, a new batch of prisoners the guy's sitting there as soon as he got in and got acclimated, he's reading his shirt, I knew we were in trouble, guy's right in your midst. So we were all lousy. The Germans did delouse us, and they used their version of DDT, whatever the hell it was, and then purple stuff, they painted you with purple stuff. That was it, and then they boiled your clothes and when they dried they gave them back to you. You'd sit around naked waiting until they handed you your clothes. That's how we were treated. The only way we were treated differently from the politicals. They even offered you the striped suits, too if your clothes were that badly damaged, and many of the guys were. I wore the striped suit in prisoners camp....kinda funny, because everybody knew that we were not political.

Everybody, whenever you got kidded, in just ordinary life, someone got too to the mark, a non-com, and would say "You found a home in the Army." That was an insult, that was a real insult. I said, "No, I had no choice in the matter. They put me in this home. And I'm just trying to make the best of it, like everybody else." You know, without stepping on someone else's toes. That's what I'm trying to do, I may not be doing such a good job." So those kind of things, it's hard to get over them now, when hopefully some acquired wisdom over these fifty years. But I don't want to deny anything that happened over there that wasn't very nice. Lot's of stuff happened that wasn't very nice. That's the thing about war, it's not very nice. The setup was a popular view of WWII as being a "good war". There really isn't.

At Camp Lucky Strike, I spent my time in the chow lines...spent my time jumping across from the so called normal chow line to the bland diet. Jeez, a bland diet, that's lazy eating. Chicken, all dripping, meat, just dripping. Oh God what delicious stuff they had, Army chili, if you could handle chili. I could handle chili, I could handle everything. Most of the long term prisoners in G Company who were captured at Anzio, captured in Italy...they couldn't eat at all. They'd have 3 spoonfuls and ...their stomachs had shrunk. And you'd look at them and their stomach was like this. There was no room, no room at all. In many respects I was very, extremely lucky, extremely lucky. The luckiest man in the world, I said that right along. Still am...luckiest man in the world, even now in my last days.

Louis Cody Wims Died in 1998

last revision